People with higher amounts of visceral abdominal fat in midlife may be at increased risk of Alzheimer's disease, according to research to be presented at the upcoming RSNA meeting.

This type of adipose tissue -- which surrounds internal organs deep in the belly -- is linked to changes in the brain up to 15 years before the earliest Alzheimer's symptoms appear, reported a team led by Mahsa Dolatshahi, MD, of Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

"[Our] findings prompt designing interventions targeted at reducing abdominal visceral fat, obesity, and insulin resistance in midlife to prevent against Alzheimer's disease pathology and neurodegeneration," the authors wrote.

The Alzheimer's Association estimates that there are currently more than six million Americans living with the disease, and by 2050, this number may increase to nearly 13 million, the researchers noted. The ubiquity of the condition makes early detection crucial.

"Even though there have been other studies linking body mass index with brain atrophy or even a higher dementia risk, no prior study has linked a specific type of fat to the actual Alzheimer's disease protein in cognitively normal people," Dolatshahi said in a statement released November 20 by the RSNA.

The team investigated any associations between brain MRI volumes -- as well as amyloid and tau uptake on PET scans -- with body mass index (BMI), obesity, insulin resistance, and abdominal fatty tissue in cognitively healthy midlife individuals. It conducted a study that included 54 participants between the ages of 40 and 60 with average body mass index of 32 (BMI measures of 30 or higher are considered to indicate obesity).

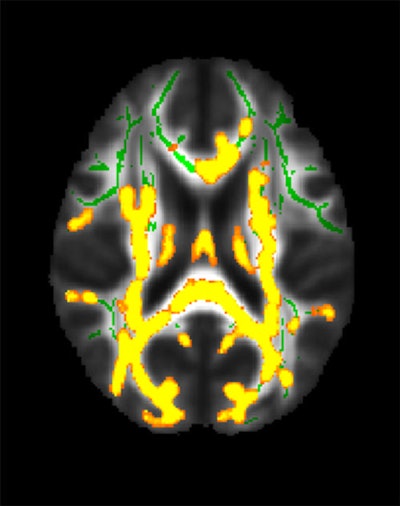

This figure shows increased neuroinflammation (yellow colors) associated with higher hidden fat (visceral fat) in the cohort of 54 participants with an average age of 50 years in the brain’s white matter. The green colors are the normal white matter. Image courtesy of the RSNA.

This figure shows increased neuroinflammation (yellow colors) associated with higher hidden fat (visceral fat) in the cohort of 54 participants with an average age of 50 years in the brain’s white matter. The green colors are the normal white matter. Image courtesy of the RSNA.

All participants underwent glucose and insulin measurements and glucose tolerance tests. Abdominal MRI exams measured each individual's volume of subcutaneous fat and visceral fat; brain MRI exams measured cortical thickness of regions affected by Alzheimer's disease. A subset of 32 patients underwent PET imaging to identify any amyloid plaque and tau tangles that would indicate the development of Alzheimer's disease.

Dolatshahi and colleagues found that a higher ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat was linked to higher amyloid PET tracer uptake in the precuneus cortex, a region affected by amyloid pathology in Alzheimer's disease – a result that was worse in men compared with women. The researchers also found that higher visceral fat measurements were linked to increased inflammation in the brain.

"Inflammatory secretions of visceral fat -- as opposed to potentially protective effects of subcutaneous fat -- may lead to inflammation in the brain, one of the main mechanisms contributing to Alzheimer's disease," Dolatshahi said.

The study results suggest a new framework for preventing Alzheimer's disease, said senior author Cyrus Raji, MD, also of the institute.

"By moving beyond body mass index in better characterizing the anatomical distribution of body fat on MRI, we now have a uniquely better understanding of why this factor may increase risk for Alzheimer's disease," Raji said.