When it comes to advanced metastatic colorectal cancer, blacks are less likely to be referred for treatment, less likely to receive it, and more likely to die sooner than whites, according to a study presented on Saturday at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

Researchers from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) and Stanford University analyzed more than 11,000 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database. Not only were blacks diagnosed with stage IV metastatic colorectal cancer less likely to be referred for specialized care and less likely to receive radiotherapy or surgery, they were 15% likelier to die before a white patient at the same disease stage.

The study team also calculated that black patients who received the same treatment as whites survived just as long -- an extra two months, on average.

"We've known for quite some time that there are disparities between black and white patients with most all cancers, especially colorectal cancer, from screening through diagnosis, to after they're diagnosed [when] they have inferior outcomes," said Dr. James Murphy, an assistant professor in the department of radiation medicine and applied sciences at UCSD, in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

"We wanted to tease out a little more about where the disparity is, so we looked at the rates of consultation as well as the rates of treatment in the various modalities for colorectal cancer," he said. "We found there were disparities pretty much across the board in that black patients were much less likely to see a specialist in consultation, and after they saw the specialist, were less likely to be treated with whatever modality, be it palliative radiation and chemotherapy or surgery."

Murphy and co-investigator Dr. Quynh-Thu Le, from Stanford's radiation oncology department, used the SEER-Medicare database to select patients with stage IV colorectal cancer ages 66 and older who were diagnosed between 2000 and 2007.

They probed the data for racial differences in consultation rates and subsequent treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation, using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models, estimating overall survival using Kaplan-Meier plots. Multivariate Cox regression models were used to determine factors that potentially explained the race-based survival differences, the authors wrote in their ASCO poster presentation.

They identified a total of 11,216 patients diagnosed with stage IV metastatic colorectal cancer during the study period, of whom 9,935 were white and 1,281 were black. After adjusting for confounding covariates, the researchers found that black patients were less likely to be seen by a surgeon, medical oncologist, or radiation oncologist.

Even when black patients were seen in consultation, they were less likely than white patients to receive primary tumor-directed surgery, liver- or lung-directed surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. Black patients also had inferior survival compared to white patients, with a mean survival time of 4.7 months, compared with 6.3 months for whites (p < 0.0001). Without adjusting the data beyond patient race, blacks had a 15% greater chance of dying than whites (p < 0.0001).

"The survival difference is small, but if you put it in context, survival differences for novel chemotherapy agents are typically measured in weeks and months," Murphy noted, adding that "survival for these patients is very short, and two months is a lot of time in a patient who has a median survival of only six months."

Taking additional factors into consideration, the group discovered the following:

- After adjusting for variables including age, gender, comorbidities, and tumor site, the risk of death for black patients increased slightly to 16% (p < 0.0001).

- After adjusting for demographic variables such as income, location, and year of diagnosis, black patients' increased risk of death decreased slightly to 10% (p = 0.004).

- After adjusting for the specific treatment received, the race-based increased risk of death was no longer seen in the data (p = 0.81).

This suggests that survival has nothing to do with race and everything to do with treatment, where the data show the disparity lies, Murphy said.

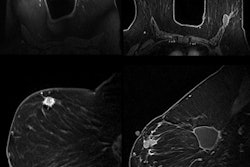

Care received for black vs. white patients

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The overall conclusion was that black patients were less likely to be referred or treated for metastatic colorectal cancer. Everyone in the population had Medicare, so it wasn't a question of being uninsured, Murphy said. Nevertheless, SEER data always impose limitations, and obtaining some patient details is always going to be a challenge with this type of study design.

"For example, while we have income data, it's so-called regional income data based on where the patient lived and what sort of income was in that area, so it's not exactly the specific patient's income," Murphy explained. "So, that said, we were able to control for income, we were able to control for geography, we were able to control for population density -- but everything we were able to control for didn't explain the differences between black and white patients."

Still, the cost of care is an important question that points to the need for additional research that the group is now conducting, he said. For example, even if patients are receiving similar treatments, are their costs similar? Also, with Medicare, patients are responsible for co-payments, and it will be important to know if co-payments might represent a barrier to treatment that differs by race. New SEER data for 2008 and 2009 have just been published, and the study results will be updated to include them, Murphy said.

"But to tell you the truth, during our study period of patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2007, we didn't see any time differences," he said. "It's a little bit frustrating because it shows that these racial differences really persisted over our study period."

"There's a lot of research on racial disparity, and this study helps us hone in a little bit in terms of disparities both before and after consultation with a specialist," he said. "Whether or not it's the same mechanism that's causing the disparity before or after is hard to say with this data, but I think it's telling us that we really need to do more detailed analyses of physician-patient interactions, physician biases, and patient biases."

"Or are there other sorts of barriers both within and outside of the healthcare system in terms of the patient environment that we're not accounting for that are resulting in these outcomes?" he added. "I think most importantly this study is showing that treatment differences really could impact survival."