By Leanne McNoulty

As a title, the "Games of the New Millennium" said it all. Sydney, Australia's 2000 Olympic Games heralded the start of a new era in competitive sport -- one in which better training techniques and healthcare management led to some remarkable performances. Many of these performances were assisted by advanced imaging techniques like musculoskeletal ultrasound, provided to athletes at the Olympic Polyclinic.

Earlier this year, I was offered the opportunity to work as a volunteer sonographer at the Polyclinic during the games. I accepted without hesitation. I knew it would be a privilege to work with a collection of extremely talented radiologists and sonographers, and I wanted to contribute for patriotic reasons as well. After all, this was Australia's chance to offer visitors from more than 120 nations a taste of the country and its culture. I wanted to be there to help make it a good experience for them.

I had the privilege of working with and also interviewing Dr. Neil Simmons, a radiologist from Jones and Partners in Adelaide, South Australia. Dr. Simmons kept meticulous records of all of the ultrasound examinations he performed or reported, and provided some of the data used in this article.

The Olympic Village housed 15,000 team members, including 10,500 elite athletes from 200 countries, and 450 doctors, coaches, physiotherapists, and managers. Following a general trend in Australian sports medicine, high-definition musculoskeletal ultrasound was used extensively to diagnose and treat sports injuries that occurred in competition.

Restricted government funding for healthcare over the years, coupled with the relatively high cost and limited availability of MRI, have given Australia an exceptionally high standard of expertise in musculoskeletal ultrasound.

Most of the country's population, and thus its elite athletes, are concentrated in just six major cities. The unique distribution pattern has created a focused referral base, enabling radiologists with expertise in ultrasound to develop close relationships with sports physicians and orthopedic surgeons, invest in state-of-the-art equipment, and meet regularly to share their experiences.

During the games, volunteer radiologists held impromptu scanning workshops where the latest musculoskeletal ultrasound techniques were demonstrated and perfected. Athletes were referred for ultrasound examinations for a wide variety of indications.

Impact injuries to the hands, arms, shoulders, and legs were most common in those competing in track and field, baseball, volleyball, basketball, boxing, diving, tennis, and wrestling. Overuse injuries were the most common among competitors in archery, track and field, canoeing, handball, rowing, sailing, swimming, and racquet sports. And there were two competitions that produced remarkable numbers of acute musculotendinous damage: weightlifting and track and field.

Calf and Achilles injuries were by far the most common reason for referral for ultrasound examination, followed by shoulder, knee, thigh, hamstring, and groin complaints. Ultrasound examinations of the ankle, hand, foot, elbow, and buttock were also performed, but were comparatively less common.

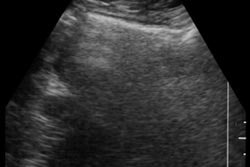

The Polyclinic used HDI 5000 scanners manufactured by ATL Ultrasound of Bothell, WA. The systems, outfitted with the company's SonoCT compound imaging technique, provided excellent detail of muscles and tendons. The acquisition of such high-resolution images led to higher diagnostic confidence when pathology was found, as was most often the case.

Achieving high-quality ultrasound images on the lean, muscular bodies of Olympic athletes was much easier than for the general population, according to Simmons, a subspecialist in sports imaging. Ultrasound's role was as important as that of MRI in achieving accurate diagnosis of musculoskeletal injury during the games, he said.

Many ultrasound-guided interventional procedures were performed on athletes, primarily for localized pain relief. Under normal circumstances, when a patient sustains a muscle injury they simply rest the limb, and the muscle or tendon heals. However, elite athletes can't always rely on this option. As a consequence, the most important question facing patients was not "Should I or shouldn’t I continue to compete?" but rather "Should I continue at all cost?"

Next page: A best-ever performance

1 2