When Dr. Josée Sarrazin moved to Malawi in 2009 to work alongside the sole permanent radiologist in the country of 14 million people, some of her colleagues questioned her judgment. After all, she would be dropping out of the North American radiology scene for a year when she had not yet reached the peak of her career.

But Sarrazin, an assistant professor of radiology at the University of Toronto, never regretted her decision and plans to return with her husband, possibly for a longer stint.

"It's absolutely one of the best moves I've ever made," Sarrazin told AuntMinnie.com, after presenting a talk about her experience at the Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR) 2011 annual meeting. "You know you can have a far greater and more direct impact on patient care than you can in North America -- your contribution makes a big difference; you're indispensable."

Sarrazin opted to make the move with her husband and their children, ages 6, 8, and 10 at the time, due to her husband's involvement with Dignitas International, a Toronto-based nonprofit, nondenominational organization started in Malawi in 2004 that helps improve access to care and treatment for HIV-AIDS patients.

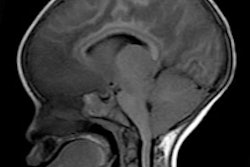

A compact portable ultrasound scanner enabled Sarrazin to perform both clinical imaging and training while in Malawi. All images provided by Dr. Josée Sarrazin.

A compact portable ultrasound scanner enabled Sarrazin to perform both clinical imaging and training while in Malawi. All images provided by Dr. Josée Sarrazin.

Sarrazin's husband, a clinical scientist and emergency room physician, developed a treatment algorithm for AIDS patients in Malawi, while Sarrazin embarked on a quest to teach ultrasound using a compact machine weighing only 6 lb (Zonare Medical Systems).

In Malawi the life expectancy is 44 years, and the rate of HIV-AIDS infection is 14% nationwide, with pockets of higher prevalence. The healthcare system infrastructure is very weak, due in part to the fact that many physicians and nurses have either died from HIV-AIDS or left the country.

Sarrazin and her family made a one-month pilot trip to Malawi and South Africa in July 2007. They decided to live for their sabbatical year in Zomba, Malawi, because Dignitas is based in Malawi. They also felt their contribution in that country would be greater and their children would gain a broader perspective of life in Africa than if they were based in South Africa.

Sarrazin had thought she would conduct a study of 100 patients with placenta previa, a goal she felt was realistic and would allow her to have a tangible impact over a short period of time. She also wanted to assess the possibility of e-mentoring by piloting an Internet connection of radiology trainees in Malawi with University of Toronto radiologists.

Instead, within 48 hours of her arrival in July 2009, Sarrazin's plans changed when she was asked by a pediatrician from Germany to help at the Zomba Central Hospital. From that day on she did rounds twice a week at the hospital, a novel situation because Sarrazin is not a pediatric radiologist.

"I worked outside of my comfort zone, for sure. But half of the people in Malawi are under 15 years old," she recalled. "There are some needs that are presented to you and you're the only one around who can help out."

With such an acute need -- at the height of malaria season, the two large rooms that served as the pediatric unit would have up to 500 children crowded two to three on and under each bed -- Sarrazin performed not only diagnosis but also procedures, such as a pericardiocentesis on a 4-year-old child with periocarditis due to tuberculosis.

Adaptability is an important trait for anyone who does a clinical stint in a developing country.

Adaptability is an important trait for anyone who does a clinical stint in a developing country.She also taught ultrasound one day a week to five young technicians who comprised the hospital's radiology department. Their knowledge of anatomy and ultrasound was very weak, due to their rudimentary equipment on complex cases. Sarrazin gradually trained them to conduct accurate abdominal and pelvic examinations and to write concise reports.

One other day a week she went to another major city in Malawi, Blantyre, and taught ultrasound to technicians at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. The country's only radiologist, Dr. Sam Kampondeni, works there.

"Sam shows up every morning and takes care of patients using an old CT machine that is broken down half the time," Sarrazin said. "And in the afternoon he has to go to his private clinic because the public hospital pays very little -- certainly not enough to feed your family."

She also did some of the work she'd set out to do in uploading images and transmitting them via the Internet with a Mac computer to the department of medical physics at the University of Toronto, despite the fact that electricity is a rare and unreliable commodity in Malawi.

There were significant challenges every day, not least of which came from the country's high morbidity and mortality rates.

"Because therapeutic options are very, very limited, we'd see children and adults simply dying of treatable conditions, which is very difficult to watch, especially coming from the first world," she said. "And the other thing I found personally extremely challenging was the endless demand and not being able to help everyone. I had a lot of guilt. It took me weeks to get used to just doing what I could, contributing to the extent that I could."

Even though their stay was devoid of many comforts and almost all electronic devices, including television, Sarrazin and her family all received tremendous satisfaction from the experience -- as evidenced by a comment from Sarrazin's 10-year-old daughter after adjusting to their new life in Africa.

"Mom, I absolutely know that I'm having the best year of my life," her daughter said.

Sarrazin and her husband plan to return when the children have grown up.