Legislation that mandates ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) of individuals entering the Medicare program hasn't had much of a direct impact on mortality since taking effect in 2007, according to Stanford University researchers.

The legislation, called the Screening Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Very Efficiently (SAAAVE) Act, provides Medicare coverage for AAA ultrasound screening in new male Medicare enrollees with a history of smoking, and in women with a family history of AAA disease. But in an analysis of a sample of Medicare enrollees, the Stanford team found that the law hasn't yielded an improvement in AAA repair, AAA rupture, or all-cause mortality rates.

In addition, a low percentage of eligible Medicare beneficiaries are receiving screening AAA ultrasound scans, according to the study published online in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

"Implementation of the SAAAVE Act is still in its early stages, but the results of our study suggest that at three years, its impact on AAA screening is modest and is based upon abdominal ultrasonography use that it does not directly reimburse," wrote a team led by internal medicine resident Dr. Jacqueline Baras Shreibati. "The low rate of abdominal ultrasonography use in this group of Medicare beneficiaries suggests that simply providing coverage for a screening test may not be sufficient to lead to widespread adoption."

The one-time screening abdominal ultrasound scan covered by the SAAAVE Act is provided as part of the "Welcome to Medicare" package for those 65 years old entering the program if they meet certain criteria: men who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes or women with a family history of AAA disease. The scan must be performed during the first year of enrollment in Medicare.

To gauge the effect of SAAAVE, the researchers gathered a 20% sample of traditional fee-for-service Medicare enrollees from 2004 to 2008. They identified 65-year-old men eligible for screening, as well as three control groups (70-year-old men, 76-year-old men, and 65-year-old women) who were not eligible for the program (Arch Int Med, September 17, 2012).

Beneficiaries were included in the study if they were eligible for Medicare based on age and not due to disability or end-stage renal disease. Those who received abdominal MRI or CT during the study period were excluded, as those studies may be used in lieu of a screening abdominal ultrasound to detect AAA.

After the exclusion criteria were applied, the researchers included 781,264 beneficiaries in the study's main analysis, including 374,310 65-year-old beneficiaries (47.9%) and 406,954 70-year-old beneficiaries (52.1%).

Logistic regression analysis was then performed to assess for any change in outcomes at one year after the exam.

No identifiable benefit

The act did not lead to changes in 365-day rates of hospitalization for ruptured AAA, elective AAA repair, or all-cause mortality, according to the researchers. No statistically significant change in outcomes was found in comparison with the reference groups of 70-year-old men, 76-year-old men, or 65-year-old women.

The researchers did find a small but statistically significant increase in abdominal ultrasound use among SAAAVE-eligible beneficiaries in comparison with the control groups in the study (p < 0.001).

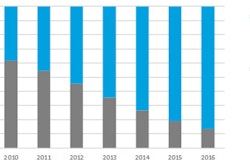

Abdominal US use among Medicare beneficiaries

|

Increased use of abdominal ultrasound was found in 65-year-old men in comparison with 70-year-old men (adjusted odds ratio, 1.15; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11-1.19) (p < 0.001). The researchers found that this increased use was still present even after excluding SAAAVE-specific AAA screening (adjusted odds ratio, 1.12; 95% CI: 1.08-1.16) (p < 0.001).

"After multivariable adjustment, we found that the association of the SAAAVE Act with receipt of abdominal ultrasonography was statistically significant but of modest size," the authors wrote.

Small effect to date

The overall direct impact of the SAAAVE Act has only been modest, according to the researchers.

"There was an 11% to 17% relative increase in abdominal ultrasonography use compared with three different control groups and adjusted for confounding factors," the authors wrote. "Furthermore, although two-thirds of men aged 65 years were eligible for AAA screening because of a history of ever smoking, fewer than 10% of men in this age group received any abdominal ultrasonography after 2007. Consequently, most men who qualified for SAAAVE Act AAA screening did not undergo it."

The primary effect of the program actually related to an increase in abdominal ultrasound studies that were not reimbursed, according to the researchers. After 2007, abdominal ultrasound experienced a significant increase during the first year of enrollment for male beneficiaries, but fewer than 3% of scans were reimbursed using the SAAAVE-specific CPT code, according to the authors.

"One possible explanation is that the SAAAVE Act encouraged physicians to order, or enrollees to request, AAA screening, even if enrollees were not eligible for SAAAVE-reimbursable screening (for example, no smoking history)," the authors wrote. "Another possibility is that enrollees were eligible for SAAAVE, and AAA screening was ordered, but the screening was billed as non-SAAAVE abdominal ultrasonography because it did not meet the complex criteria for reimbursement, which required screening to take place after the Welcome to Medicare examination, within one year of taking up Medicare Part B."

Furthermore, ordering physicians may have been reluctant to use the SAAAVE-specific CPT code due to fear of not being reimbursed, according to the researchers.