AuntMinnie.com presents the 15th in a series of columns on the practice of ultrasound from Dr. Jason Birnholz, one of the pioneers of the modality.

Fellow Ultrasounder,

I really appreciate invitations to lecture away from home. There's the obvious ego boost when your colleagues and peers believe you can share knowledge with them, and I have been very fortunate over the years in getting a chance to visit colleagues all around the globe. But far from being a one-way flow of information, I always felt that I learned more than my hosts and audiences.

That also happened a few weeks ago when I was honored to receive a lifetime achievement award from the Israel Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG). On this trip, I gleaned an insight about our work that I had never put into words before. To adequately share it, though, I need to take you back to my beginnings in ultrasound and in radiology.

The 1960s (a fabulous time)

Sometimes I mention "cognitive dissonance" when people ask me to talk about the history of ultrasound. As physicians, we strive to be completely truthful; we acknowledge our "mistakes" when they involve patient care because that is how we learn and maintain objectivity. But for something innocuous like personal remembrances of the past, it's all too natural to replace something we did or didn't do or thought with something a bit more favorable -- that's resolution of cognitive dissonance in action.

Dr. Jason Birnholz.

Dr. Jason Birnholz.

I'm trying to keep that in mind as I attempt to recreate my time as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service, posted to the clinical center at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, in 1968. I had started my tour as a cardiology hopeful, assigned to a program researching exercise stress testing for early detection of occult coronary artery disease. My interest in ultrasound was piqued by its possibilities for monitoring myocardial dynamics.

I was able to locate and receive on loan one of the world's first mechanical sector scanners from Magnaflux. The scanner was stillborn commercially when Magnaflux's parent company closed it down soon after initial product development. It had a very narrow field-of-view and only operated at about seven frames per second, which was sort of useful for the mitral valve but not much else.

However, I started looking at livers, performing more like a kind of sonic biopsy since the field-of-view was so restricted. I transferred to the Cancer Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), where I had the incredible opportunity to scan patients and then assist in the operating room during their laparotomies. I had also obtained an Aloka B-mode machine, very possibly the only one in the U.S. at the time.

Diagnostic radiology residency

I next embarked on clinical B-mode scanning with no background at all. I interviewed the pioneers I could find on the East Coast and read what I could find (in English). It became clear that I needed to learn about imaging, so I applied for a diagnostic radiology residency. My first interview was at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), where I wound up when my tour of duty ended.

The radiology department faculty at MGH included Dr. Douglass Howry, whom I think of as the founder of ultrasound. He made his own water bath sector scanner a year after finishing medical school in Colorado in 1947 and went on to refine it with engineers Bliss and Posakony. He then associated with the nephrologist Homes in the early 1950s in a series of clinical applications.

Somewhere along that path, he finished a radiology residency himself. Unfortunately, Howry was away when I had my interview. He had not set up an ultrasound facility at MGH, but it was suggested that in my free time I might work with him toward that end. If only. Before I moved to Boston, he died of a massive myocardial infarction while boating. So I never had the chance to meet him or learn of his vision for the field he made possible.

My NIH equipment was donated to MGH, and I was able to start a clinical ultrasound service while I was a resident. This wasn't as precocious as it might seem; diagnostic radiology residents of that era usually did something else first, such as an internal medicine residency or an equal number of years of general surgery. My coresidents could each have done something similar with the skills they already had.

Our radiology residency had lots of time devoted to pathology, including weekly correlation conferences for the entire department and rotations in anatomic pathology. The objective was to relate any and all imaging findings -- for all modalities and techniques -- to both the gross and microscopic anatomy of a case.

I don't want to imply that this was special to MGH. I believe and assume that it is an integral part of all approved residencies everywhere. In fact, this orientation is something I took for granted and never thought to bring up with my closest radiology colleagues in other countries such as Switzerland, the U.K., China, Japan, Singapore, Greece, South Africa, and Colombia.

My 1st lecture and the original Aunt Minnie

The first time I was invited to give a talk out of state, complete with an honorarium and a plane ticket, was I think in 1973 or 1974 by Dr. Michael Grossman for the newly formed ultrasound unit in the department of radiology at the University of Cincinnati. This was the department headed for ages by Dr. Ben Felson. He was, and deserved to be, an absolutely iconic figure in 20th-century diagnostic radiology.

I have a recollection of Felson expressing his notion of pattern recognition in interpreting chest films by saying something like, "When your Aunt Minnie walks into a room, you know who she is instantly, without having to think about any of her visible properties or features." This understanding of the role of unconscious thought in our work is scarily prescient of current psychological research on the subject from Dijksterhuis et al (Perspectives on Psychological Science, June 2006, Vol. 1:2, pp. 95-109).

I don't think I really understood the brilliance of this metaphor until I started to write this article. The Aunt Minnie concept needs to be viewed against the central panorama of pathology (and pathophysiology) in radiologic education. When a physician begins with a patient, there is a probabilistic process and conscious listing of the likely diagnostic possibilities, always ordered from the worst thing that might be present to the least urgent. Obviously, there will be a big difference if you have an unconscious person brought into an emergency room versus an outpatient appearing for a preventive health session.

The next stage of diagnosis, and the one that pertains to image interpretation, is causal: determining the specific form of pathology or pathophysiology that resulted in the image findings. This is the goal no matter what form of imaging you are using, ultrasound included.

When you have seen a lot of images and you have a thorough grounding in the pathology underlying the images, and you possess a complete understanding of that imaging process, the recognition and initial identification of abnormalities are generated by unconscious mechanisms.

The ISUOG

With that background in mind, I'llreturn now to my recent trip to Israel. The ISUOG said a lot of nice things about me when I was introduced, and I will always be grateful.

The Israeli birthrate is something like 3.4 children per couple. It is a semisocialized healthcare system with all pregnant women mandated to have at least two ultrasound exams: one in the first trimester and another at about 20 weeks that is only to be performed by a physician from a limited pool that has been specially certified. The group consists mainly of obstetricians plus a handful of radiologists. Like here in the U.S., there doesn't seem to be much direct cooperation between these two specialties.

The Israeli patient population is young and fit, and the overwhelming clinical concern is recognition of malformations and/or aneuploidy, with, I suspect, a lot less worry about premature labor, diabetes, hypertension, and growth retardation than here in the U.S. I, the Israelis themselves, and most others believe that on a national level, they are the best in the world for finding or excluding structural problems in fetuses. This made the invitation and award even more special for me.

I knew there was probably nothing about the recognition of congenital anomalies that I could tell them or that they might listen to, so I constructed my first talk along the lines I would have followed if the RSNA had asked me to do a plenary session talk. I started with some basic perceptual psychology concerning display phase and pseudocoloration of images (below) before moving on to the main topics that had to do with cytogenetic foundations of fetal development and their influence on image findings.

A 9-week embryo with a physiologic type umbilical hernia from "Foundations of Ultrasonic Fetal Screening for Congenital Anomalies," presented by Dr. Birnholz in Tel Aviv in April 2014. All images courtesy of Dr. Birnholz.

A 9-week embryo with a physiologic type umbilical hernia from "Foundations of Ultrasonic Fetal Screening for Congenital Anomalies," presented by Dr. Birnholz in Tel Aviv in April 2014. All images courtesy of Dr. Birnholz.I thought I would focus on one of the mysteries of genetic expression: How is it possible that the same syndrome can have different major features in different afflicted children? That is a kind of variability on an organ level. The same process is just as striking on a tissue level, especially if we cling to the notion that if cells look alike histologically, then they are truly the same. Psoriasis is a good example; this is a genetic condition. When it is triggered by some immune or environmental factor, a rash occurs but large areas of skin are spared. You have all seen fatty infiltration of the liver in a geographic pattern. And it is the same process that underlies the skip areas of presentation of Crohn's disease and celiac disease in the gastrointestinal tract.

I alluded to the new field of transcriptional architecture that maps genotypes within tissue slices. One of the early findings about the developing brain is that this tissue is uniquely homogeneous in its genotypic features. A recent report described patches of disordered cytoarchitecture in the frontal and temporal cortex in autism. These are believed to have resulted from islands of altered genetic expression during fetal development, when there is uniform and apparently normal cellular morphology (Stoner et al, New England Journal of Medicine, March 27, 2014, Vol. 370:13, pp. 1209-1219). As molecular biology advances, we will have to extend our capabilities as well. John Landon Down described the clinical features of trisomy 21 in the mid-19th century and the association with an extra chromosome occurred in the mid-20th century.

I had chosen a blend of imaging technology and the molecular foundations of ultrasound image findings in fetuses, with a minimum of nitty-gritty things about simple pattern recognition. When I had finished, I felt I had disappointed them all and that no part of that failure could be blamed on language.

A live exam

The highlight of the meeting was a live demonstration of fetal echocardiography by Dr. Israel Shapiro, who has been concentrating on this application longer and probably more expertly than anyone else in the ISUOG. He had not seen the patient before.

He performed the exam in seclusion, and it was piped in high-definition video to the auditorium. During the stepwise sequence of the study, he identified an aberrant origin of the right subclavian artery, which is not only impressive but significant, as this has about a 20% association with aneuploidy, even as an isolated finding.

The fetus was initially prone, and there seemed to be a fair amount of poking and prodding and changing mom's position to get the fetus into a better position for scanning, which is pretty common. But the scanning itself seemed pretty jumpy to me. The dialogue was in Hebrew, which I don't understand, but my friends told me that a lot of the narration was about achieving four-chamber and three-vessel views. The exam included B-mode imaging and color Doppler. All other features of the heart and great vessels were normal and very well-demonstrated.

Irreconcilable differences?

The jumpiness of probe movement kept nagging at me. I had always tried to convey to radiology residents and fellows in my academic days that they were to "inspect" whatever region they were looking at, and when they found something of interest, they should center it in the field and rotate the probe. At the same time, they were to reserve a little attention for readjusting the equipment as necessary to maintain the best image quality and decide if their current transducer was really best.

"Inspect" was the only term I could think of, but it was always understood because everyone had the same basic concept drilled into them about seeking a causal pathology-based diagnosis. The "view" was not particularly important, as the examiner was always seeking to evaluate a volume, even though individual frames were by necessity cross-sectional.

Specific views were treated as entry-level aids while one was acquiring the mental and physical coordination that prior generations of radiologists had applied to x-ray fluoroscopy or multiple plane films in orthogonal or oblique planes. In fetal imaging, views are always oriented by fetal position, not the transverse or longitudinal grid superimposed on people supine on an exam table.

I've never thought there was any difference between sorting out volumetric findings from a set of posteroanterior and lateral chest films and seeking a volumetric understanding of ultrasound findings from cross-sectional planes, no matter how they are oriented. I would think this is at the other side of the same conceptual mirror of a surgeon making a linear incision with a scalpel while keeping the volume anatomy of the region clearly in mind.

I recall introducing pediatric cardiology fellows to fetal echocardiography in the late 1970s and never having to work through specific "views," because their knowledge of fetal cardiac embryology and morphology was so excellent and definitely better than my own. They had no difficulty in thinking of the heart, not just about pictures of the heart.

Fetal echocardiography is an apt case to analyze because antenatal ultrasonic recognition of structural heart disease has always had the poorest performance statistics in large surveys. Naively, I had always wondered why this was so, or, indeed, why facilities that did a lot of fetal scanning frequently referred out routine screening cases for selective fetal echocardiography.

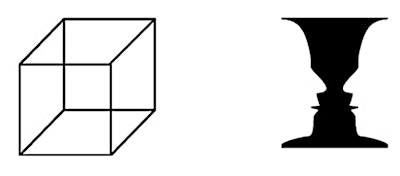

My opinion, with all the usual reservations about generalizing about any facet of medical practice, is that we have multiple communities doing ultrasound in separate applications and they may have absolutely different conceptual biases. Those who utilize ultrasound without a full, traditional imaging sciences background cannot understand the mindset of those who do, and those who have the knack of the gestalt typically cannot express the Aunt Minnie-ness they have internalized and use unconsciously. I wonder if this might be like only ever seeing one part of a Necker cube or a reversed figure?

Examples of a Necker cube and reversed figure.

Examples of a Necker cube and reversed figure.Perspective

There is a lot to be said for what I think of as "checklist" ultrasound based on specific "views" and looking for isolated "signs." It can work really well for limited local questions, such as to identify the presence or absence of nuchal translucency in a fetus. It is fast and efficient, and it can be spread rapidly over a large population via a cadre of minimally trained technologists or co-opted nurses, therapists, or physicians.

It is also more in keeping with a major trend in healthcare toward attention and immediate treatment of localized problems, combined with some blanket preventive health measures for the most common systemic problems. Ultrasound done this way is typically not considered definitive and usually involves confirmatory testing.

The alternate, classic radiologic scheme was the standard at the introduction of the first high-performance phased-array devices in the early 1980s. Relatively few centers were able to support specialists with the requisite skills and knowledge base. Attention was given to systemic conditions and to more of the ideal in terms of sequencing exams needed for individualized patient care.

Fetal imaging was kind of a special case because radiologists had spent the past 50 years or so avoiding x-ray exposure for pregnant women; there hadn't been an educational need to explore fetal pathology to the same degree that a neuroradiology rotation would explore the brain and spine.

For a variety of reasons, many radiologic facilities in the 1980s took the easy route of adopting checklist ultrasound for obstetric cases. As a result, I suppose that subsequent educational generations of radiology residents -- deprived of fluoroscopy and its direct patient contact applications, having diminishing ultrasound case responsibilities, and overwhelmed by the rapid changes in CT and MRI -- tended to regard ultrasound as an imaging orphan not worthy of the more demanding causal unconscious pathology-based paradigm that remained the standard in other forms of imaging.

By this point, you may have come to the conclusion that this is just an old guy saying things were so much better in the past or bemoaning why ultrasound has never become part of mainstream radiology. Really, though, the old times weren't that great anyway. For ultrasound, you could never see as well as you needed to, the general credibility of the entire method was always suspect, and there was way too much controversy among its practitioners, all of whom would have gained from more collegial cooperation and sharing.

I think this look at how we approach images and imaging is important and timely because we are again on the brink of a major improvement in ultrasound imaging technology. We all need to start planning now about the kind of exam we should be doing next year, whether it be as a physical exam tool with an enhanced point-of-care device or with the highest performance "mainframe."

It's time to relearn what Ben Felson and every other chest radiologist of that era knew and did when Aunt Minnie came to visit. For me, I'd get right up, give her a big hug, and welcome her back home.

Dr. Jason Birnholz was one of the few advanced academic fellows of the James Picker Foundation, and he has been a professor of radiology and obstetrics. He is a fellow of the American College of Radiology and the Royal College of Radiology, and he was an associate fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnie.com.