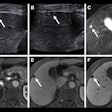

Using ultrasound to identify liver damage in alcoholic patients helps inform treatment decisions in this population and may even lead to improved prognoses, according to a study published online in Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

Liver disease due to alcohol use can manifest in a variety of conditions: steatosis, steatohepatitis, acute alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis of the liver, and hepatocarcinoma. Some of these can be reversed or mitigated if the patient quits drinking. For example, steatosis without inflammation can be reversed if drinking is stopped. Once steatohepatitis has been established, liver damage can't be fully reversed, but quitting alcohol can lessen portal hypertension.

And since alcoholic patients tend to be more vulnerable to hepatitis C, a timely diagnosis can lead to better prognosis and treatment planning, wrote a team led by Dr. Daniel Fuster of Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain (Drug Alcohol Depend, July 19, 2018).

Although ultrasound is regularly used to diagnose nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, it's less frequently used for the screening and early detection of liver disease in patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), the authors noted.

"New strategies aimed at the early detection and treatment of liver-related conditions are needed for this population. Liver ultrasound is an easy-to-perform technique that is rarely used in asymptomatic patients with AUD," the team wrote. "We aimed to describe ultrasound findings of liver disease in patients seeking treatment for AUD."

Common cause

Liver disease is a leading cause of death around the world and can include chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic liver disease. But disease related to the consumption of alcohol is on the rise, according to Fuster and colleagues.

"Both in the U.S. and some European countries, there has been an increase in liver-related mortality due to end-stage liver disease, mostly because of the impact of alcohol consumption," the group wrote.

For the study, Fuster's team used abdominal ultrasound to identify steatosis (fatty liver), hepatomegaly (liver enlargement), heterogeneous liver, and portal hypertension in 301 patients with median age of 46 and alcohol consumption of 180 grams per day for at least 10 years. The group defined analytical liver injury as at least two of the following:

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels between 74 and 300 units per liter (U/L)

- AST/alanine aminotransferase ratio of greater than 2

- Total bilirubin of more than 1.2 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL)

The group defined advanced liver fibrosis as a Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score of 3.25 or higher (scores range from < 1.45 to > 3.25).

Among the patient cohort, prevalence of the hepatitis C virus was 21.2%, AST levels were 42 U/L, and ALT levels were 35 U/L (indicating liver enlargement or mild to moderate fatty liver disease); 16% of patients had analytical liver injury and 24% had advanced liver fibrosis.

Of all the patients, 77% had at least one ultrasound abnormality, and 45% had at least or more than two. Abnormal ultrasound findings included the following:

- 57.2% steatosis

- 49.5% liver enlargement

- 17% heterogeneous liver

- 16% portal hypertension

Patients with hepatitis C had a higher incidence of heterogenous liver and portal hypertension compared with those without the infection (25.4% versus 14.5% and 27.1% versus 13.8%), the group found.

"Liver damage is a major driver of disease burden in patients with unhealthy alcohol use, and liver disease is often diagnosed in advanced stages," Fuster and colleagues wrote. "Results ... indicate that there is a need for the assessment of liver damage in patients seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder."

Another tool in the arsenal

The consumption of alcohol is associated with liver disease progression and increased risk of alcoholic hepatitis, according to Fuster and colleagues. So using abdominal ultrasound in patients seeking treatment for alcohol dependency could be helpful for making clinical decisions and taking appropriate therapeutic action. Perhaps it could even give patients more incentive for quitting drinking, the group wrote.

"Liver ultrasound appears to capture a significant proportion of mild to moderate abnormalities in patients who do not meet the [analytical liver injury] or [advanced liver fibrosis] criteria," the team concluded. "In this regard, the use of ultrasound to detect early stages of liver disease may promote alcohol cessation."