Although there were some variations in performance, it may not be necessary for users of ultrasound scanners to receive special training before scoring lung exams of patients with COVID-19, according to research published May 21 in Nature.

A group of researchers led by Dr. Markus Lerchbaumer from Charité Institute of Radiology in Berlin, Germany, found that while different types of observers had "fair to moderate" interobserver agreement in interpreting specific lung findings in patients with COVID-19, a little background in lung ultrasound goes a long way.

"As long as observers have some experience in lung ultrasound, no specific clinical background is needed for scoring the findings, even though specific expertise is often reported as a requirement," the authors wrote.

Examining the lungs in patients is usually performed with nonenhanced CT scans, but point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is being looked at as a safer method since patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus would not need to be transferred, and risk of exposure for medical staff would decrease.

The researchers said lung ultrasound may have a big advantage for COVID-19 due to its widespread availability and cost-effectiveness.

"Additionally, lung ultrasound has emerged over the last two decades as a noninvasive tool for the fast differential diagnosis of pulmonary diseases and is now used in different settings in intensive care," they wrote.

In the current study, 10 observers from three different medical specialties participated in rating 100 lung ultrasound images from 13 patients. These included observers specializing in intensive care medicine, emergency medicine, and physiology.

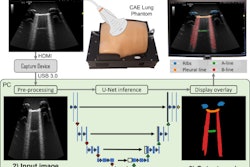

Images were acquired by a radiologist using a hand-held POCUS system (Viamo sv7, Canon Medical Systems) performed at the bedside. Ultrasound presets were optimized for lung ultrasound.

Through an online tool, observers could use multiple-choice options with predefined answers for rating the scans. Options included typical COVID-19-associated lung ultrasound findings; these included the following:

- Pleural thickening and fragmentation

- Presence of B-lines subclassified in single or confluent, subpleural consolidations

- Positive air bronchogram

Selecting none of these pathologies was also an option.

The team found that observers in the intensive care unit tended to interpret B-lines more accurately, while physiology researchers and emergency physicians more often categorized B-lines as confluent rather than single. This tendency became even stronger over the course of viewing instances, probably explaining the poorer than expected overall inter- and intraobserver agreement.

"We assume that ICU observers have greater clinical experience with patients with severe ARDS or cardiogenic edema and their corresponding lung ultrasound findings, especially compared to scientists whose experience relies on lung ultrasound in rodents," they wrote.

ICU observers, on the other hand, differed from the latter two groups regarding the identification of pleural thickening.

Meanwhile, agreement was highest for more distinct lung ultrasound findings such as air bronchograms and subpleural consolidations, as well as more severe lung ultrasound scores.

The researchers wrote that training lung ultrasound users may improve agreement and clinical feasibility. They also suggest that training material used for lung ultrasound in POCUS should pay better attention to areas such as B-line quantification and differentiation of intermediate scores, which revealed only "mediocre" agreement in the study.