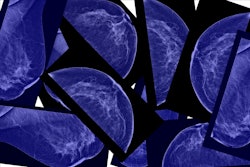

Messaging on breast cancer screening cessation can impact older women’s intentions to stop, suggest findings published August 19 in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers led by Nancy Schoenborn, MD, from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD, found that a breast cancer screening cessation message significantly increased older women’s intentions to stop undergoing annual mammography.

"The message is intended to make women aware that stopping screening is an option, and may be the right decision for some women," Schoenborn told AuntMinnie.com. "It is also intended to inform women about the potential harms of overscreening so they can make an informed decision."

Health experts continue to debate whether older women, particularly elderly women, should undergo annual breast cancer screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends biennial screening for women up to 74 years of age, a B-grade recommendation. In contrast, the American College of Radiology (ACR) does not have an age limit for annual screening.

The researchers highlighted that elderly women may be at risk of being overscreened. Previous reports suggest that about half of women over the age of 75 and more than 40% of women with a life expectancy of 10 years or less undergo breast cancer screening.

Schoenborn and co-authors studied the impact of messaging on older women’s support for and intentions of stopping breast cancer screening. They used a pilot-tested cessation message delivered to a hypothetical older woman with serious illnesses and functional impairment. The message was described as from one of three sources: a clinician, a news story, or a family member. The researchers issued an online survey in two waves in 2023 to participating women.

The team randomized participants into one of four groups: no message (control), a single message from a clinician at wave 1 and no message at wave 1 (group 2), a message from a news story (wave 1) and a clinician (wave 2) (group 3), and a message from a family member (wave 1) and a clinician (wave 2) (group 4).

To measure support to stop screening, the team used a 7-point scale. A score of 1 indicated “definitely should get a mammogram,” while 7 indicated “definitely should not get a mammogram.”

The final analysis included data from 3,051 women who completed wave 1 of the trial, and 2,796 women who completed wave 2. Women ages 65 and older were included in the trial, and the average age of participants was 72.8. Of the total women, 2,506 were non-Hispanic white and 272 were non-Hispanic Black.

Group 2 showed significantly higher support for stopping screening in the hypothetical patient at wave 2 (average score, 3.14, with 1 as reference) compared with the control group (average score, 2.68; p < 0.001).

Groups 3 and 4 had higher scores (4.23 and 4.12, respectively) compared with the control group and group 2 (p < 0.001).

“Message effects on self-screening intentions followed a similar pattern, with larger effects among participants 75 years or older or with limited life expectancy,” the researchers noted.

Schoenborn added that healthy older women in the study who should not yet stop screening were not discouraged to screen. However, the more frail or ill older women who were recommended to stop screening reported higher intentions to stop.

Schoenborn added that clinicians and radiologists can use such information as feasible communication tools for their patients.

"It is not our intention to be overly prescriptive for how clinicians would discuss with an individual patient or to dictate the decision for any women," she told AuntMinnie.com.

The team called for future research to engage with potential messaging sources to study the feasibility and acceptability of multilevel messaging strategies and their effect on screening behavior.

The full study can be found here.