The presence of breast arterial calcifications (BAC) on a screening mammogram doesn't necessarily signify that a woman has coronary heart disease (CHD), according to a new study published in the February issue of Radiology.

Researchers at Staten Island University Hospital in Staten Island, NY, examined whether, in women who had cardiac catheterization, breast arterial calcifications seen at screening mammography correlated with coronary heart disease (Radiology, February 2010, Volume 254:2, pp. 367-373). Mammograms were considered positive for BAC when the calcification was found on one of two standard views in the right or left breast, or in both breasts.

The presence of breast arterial calcifications in screening mammography and their link to coronary heart disease has been well studied but remains unresolved, according to the study. It's a frustrating state of affairs because if such calcifications were a CHD marker, it would make screening mammography an even more powerful test for women's health.

"Many investigators have studied BAC and cardiac risk factors ... [but] there is no substantial convincing evidence that links BAC to CHD lesions seen at angiography. ... If BAC were found to be a marker for CHD, there would be major public health benefits to using a single diagnostic test to screen for two diseases," wrote Dr. Mario Castellanos and colleagues.

It's this lack of clarity about what the presence of BAC means that leaves many clinicians undecided about whether BAC findings should prompt a stringent cardiac evaluation.

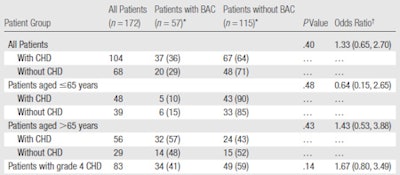

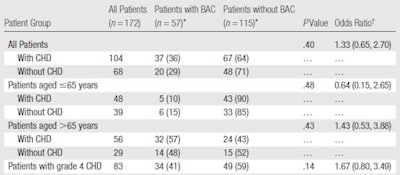

In their study, Castellanos and colleagues looked at 172 women (mean age, 64 years) who underwent coronary angiography. The women were divided into two groups: those with CHD (104) and those without (68). The study team identified the severity and location of coronary heart disease, and reviewed screening mammograms that had been acquired within one year of cardiac catheterization for presence of breast arterial calcifications. Women who had not received a mammogram in that time period underwent one as part of the study.

Thirty-seven of the women with CHD (36%) had breast arterial calcifications and 20 women without CHD (29%) had BAC (p = 0.40), for a total of 57 BAC-positive mammograms. But because the results aren't statistically significant, they demonstrate that BAC and CHD are not associated, Castellanos said, although he conceded that the study sample was small.

"Any time you have a negative study, you do have to ask yourself whether you sampled enough," he told AuntMinnie.com. "But at least with the number of patients we included in our study, we didn't see an association [between the two conditions]."

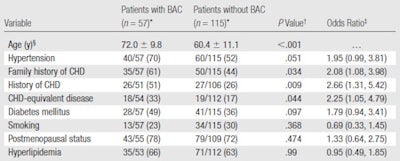

The group found that women with a family history of CHD had a higher incidence of breast arterial calcifications compared to women without a family history of the disease. Approximately 61% of patients with BAC, compared with only 44% of patients without BAC, had a family history of CHD (p = 0.034).

| Frequencies of BAC among patients with and those without CHD |

|

|

Data were calculated by defining CHD as grades 1-4 and by using BAC as a dichotomous variable -- that is, as either present or absent. * Numbers in parentheses are percentages. † Numbers in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. All tables courtesy of the Radiological Society of North America. |

"We identified a significant association between BAC and cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, and stroke) despite the fact that BAC was not associated with angiography-depicted CHD," the researchers wrote. "A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the origin of CHD in women is more complex than simply the development of an obstructive lesion in the coronary circulation."

| Associations between cardiac risk factors and BAC status |

|

|

Values are based on the associations between cardiac risk factors and BAC status in the 172 study patients. * Unless otherwise noted, data are numbers of patients, with percentages in parentheses. The denominator is smaller than the total number of patients in the given BAC group in some cases because the history of CHD, CHD-equivalent disease status, menopausal status, and presence or absence of hyperlipidemia were unknown for some patients. † P-values for categorical variables were computed by using two-tailed Fisher exact tests. ‡ Numbers in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. § Mean age ± standard deviation. CHD-equivalent disease refers to peripheral vascular disease, angina, transient ischemic attack, or stroke. |

The mean age of patients with breast arterial calcifications, 72 years ± 9 years, was older than the mean age of patients without BAC, 60 years, ± 11 years.

Finding breast arterial calcifications in screening mammograms can act as a prompt to give a woman age-appropriate breast screening -- something doctors should already be doing. But it doesn't mean a woman should go directly to a stress test, according to the researchers.

"We advise caution in using BAC as the only indication for initiating an extensive cardiac workup," they wrote. "It seems more prudent to screen for the classic modifiable cardiac risk factors, such as smoking, dyslipidemia, diabetes, family history of CHD, and metabolic syndrome."

By Kate Madden Yee

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

January 27, 2010

Related Reading

Breast screening could pull double duty for tracking heart disease, June 1, 2004

Heart disease risks tied to fat distribution in women, May 27, 2004

Breast radiotherapy linked to heart disease deaths, March 18, 2004

Breast cancer can recur in interpectoral lymph nodes, February 19, 2004

Mammogram findings indicate higher risk of heart disease, December 4, 2002

Copyright © 2010 AuntMinnie.com