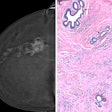

Mammograms should not be done on a one-size-fits-all basis, but instead should be tailored to factors such as a woman's age, her family history of breast cancer, and her own values -- but particularly the density of her breasts, according to a new study in the July 5 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study challenges current mammography screening guidelines from groups such as the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which recommend one frequency -- either every year or every two years -- for all women.

It indicates that using age as the primary factor to decide when to start screening mammography isn't enough, said lead author Dr. Steve Cummings from the San Francisco Coordinating Center at the California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute.

"Our study shows that other factors, particularly breast density, are just as important, if not more so, in helping a woman decide what is most appropriate for her," he said. "We show that mammography should be personalized. The best interval for you depends on your age, breast density, and other risk factors for breast cancer."

Model-based study

Cummings and colleagues used data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program; and the medical literature. The team developed a model to compare the lifetime costs and health benefits for women who got mammograms every year, every two years, every three to four years, or who never received a mammogram (Annals of Internal Medicine, July 2011, Vol. 155:1, pp. 10-20).

The women all had different risk factors for breast cancer, and the model assumed that all began as healthy individuals but could subsequently fall into one of five different categories:

- Remain healthy

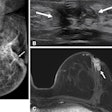

- Develop ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

- Develop localized invasive breast cancer, regional invasive breast cancer, or distant invasive breast cancer

- Die from invasive breast cancer

- Die from causes other than breast cancer

The authors used the data to estimate how many extra mammograms over 10 years would be needed to prevent one death from breast cancer in those having mammograms once every three to four years compared to no mammograms, and in those having mammography every two years compared to once every three to four years. They also estimated the costs for each frequency of mammography for each year of quality life gained.

When should screening start?

The study showed that women with a first-degree relative with breast cancer or with a history of a breast biopsy should have an initial screening mammography at age 40. And if the woman's breast tissue is dense, screening is all the more crucial, according to the researchers.

"For women age 40 to 49 with high breast density and with either a first-degree relative with breast cancer or a prior breast biopsy, the benefits versus harm for performing mammography every two years is similar to screening an average-risk woman in her 50s," according to study co-author Dr. Karla Kerlikowske from the University of California, San Francisco. "This amounts to about 20% of women in their 40s. For women age 40 to 49 without these risk factors, it is reasonable to wait until age 50 to start mammography screening."

Cumming's team found that yearly mammography was not cost-effective, in that it was expensive and yielded little additional health benefits compared to mammography once every two years, regardless of breast density or other risk factors. The frequency of mammography, however, is not just a clinical decision: It also carries a strong emotional component, according to the group. False-positive mammography results can cause significant anxiety; thus, the effect of the exams on a woman's quality of life should be considered in her decision about when to start screening as well.

But not everyone agrees with the study's conclusions. Basing screening protocols on risk factors isn't necessarily the best approach, according to Professor Stephen Duffy of Queen Mary, University of London. Duffy recently authored a study in Radiology that suggests the benefits of mammograms are even greater than previously thought (Radiology, June 28, 2011).

"The trouble with risk-based screening is that you get a marginally more cost-effective strategy for screening, but it ignores the hidden cost of additional complexity," Duffy told AuntMinnie.com. "Having a program based on age has the advantages that everyone understands it, risk is very strongly related to age, and the marginal cost of determining age is close to zero. There is a strong feeling that the success of the U.K. program is partly due to its one-size-fits-all simplicity."

The new study also spotlights the importance of breast density and cancer risk. Awareness about breast density has increased since 2009, when the state of Connecticut passed a law that mandates that women receive notification on their breast tissue density after a mammogram. Now many more states are drafting or presenting similar legislation, including California, Florida, Kansas, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, and Ohio. Last month, Texas Gov. Rick Perry signed that state's version of a breast density notification bill, "Henda's Law," into law; it will take effect September 1.

As these efforts move forward, the authors of the new study say that their findings indicate a need for better stratification of breast cancer risk and the cost-effectiveness of screening mammography.

"We believe that considering breast density, previous biopsy, and family history of breast cancer when deciding on a mammography screening strategy is appropriate," the authors concluded.