A research paper published on Thursday by the British Medical Journal has cast fresh doubt on the value of breast screening by suggesting that declining mortality rates are due more to improvements in treatment and the efficiency of healthcare systems than mammography screening.

"A growing number of people are asking questions about the evidence behind screening. We have to get rid of the infatuation with mammography and take a look at the hard facts," said lead author Dr. Philippe Autier, research director at the International Prevention Research Institute in Lyon, France. "Our findings don't support the mass screening of women and show that screening by itself has little detectable impact on mortality due to breast cancer."

It's time for radiology to end its infatuation with mammography, according to Dr. Philippe Autier.

It's time for radiology to end its infatuation with mammography, according to Dr. Philippe Autier.

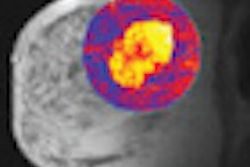

In an exclusive interview with AuntMinnieEurope.com, he advised radiologists to give much greater consideration to other emerging diagnostic methods, particularly MRI, although he conceded that worries persist about breast MRI's cost-effectiveness.

Autier also urged decision makers to look more closely at how breast screening is organized and implemented. He noted that huge differences exist in how screening is performed across Europe, and there is a particularly serious shortage of reliable data in both France and Germany. He added that he was disappointed himself about the findings, and he was prepared for a strong reaction from the supporters of breast screening.

Autier and his co-authors from France, the U.K., and Norway studied statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO) mortality database on cause of death between 1980 and 2006, as well as data sources on risk factors for breast cancer death, mammography screening, and cancer treatment. They found that from 1989 to 2006, deaths from breast cancer fell by 29% in Northern Ireland, 26% in the Republic of Ireland, 25% in the Netherlands, 20% in Belgium, 25% in Flanders, 16% in Sweden, and 24% in Norway (BMJ, July 28, 2011).

These trends in breast cancer mortality rates varied little between countries where women had been screened by mammography for a considerable time, compared with those where women were largely unscreened during that same period, the authors wrote. Furthermore, the greatest reductions were in women ages 40 to 49, regardless of the availability of screening in this age group.

From 1965 to 1980, cervical cancer mortality fell earlier and more strongly in Nordic countries that implemented nationwide screening programs, compared with those that delayed screening. Autier's team used a similar approach to compare trends in breast cancer mortality within three pairs of European countries: Northern Ireland versus the Republic of Ireland, the Netherlands versus Belgium and Flanders, and Sweden versus Norway.

The researchers expected a reduction in breast cancer mortality would appear sooner in countries with earlier implementation of screening. Countries of each pair had similar healthcare services and level of risk factors for breast cancer mortality, but were different in that mammography screening was implemented about 10 to 15 years later in the second country of each pair.

"The contrast between the time differences in implementation of mammography screening and the similarity in reductions in mortality between the country pairs suggest that screening did not play a direct part in the reductions in breast cancer mortality," they wrote. "Improvements in treatment and in the efficiency of healthcare systems may be more plausible explanations."

Breast cancer mortality in the paired European countries with similar socioeconomic status and access to treatment was comparable after 1989, despite the 10 to 15 year difference in mammography screening implementation. The downward trends in mortality started before or shortly after the implementation of the screening program. The researchers also found the greatest reductions were in women ages 40 to 49, regardless of the availability of screening in this age group; reductions in women ages 70 to 79 were highly variable and did not correlate with the timing of screening in younger age groups.

Autier published another article in the BMJ last August about disparities in breast cancer mortality trends between 30 European countries (BMJ, May 2010, Vol. 341, pp. c3620). In a retrospective trend analysis of the WHO mortality database, he found that changes in breast cancer mortality after 1988 varied widely between European countries. Women younger than 50 showed the greatest reductions in mortality, and in countries where screening for that age is uncommon. The increasing mortality in some central European countries reflects avoidable mortality, according to the article.