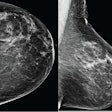

The screening mammography debate has come to the September issue of Radiology through a pair of articles from the most vociferous advocates on either side: One group is led by Dr. Daniel Kopans of Massachusetts General Hospital and the other by Drs. Peter Gøtzsche and Karsten Jørgensen of the Nordic Cochrane Centre.

Key to the debate is the issue of overdiagnosis, with Gøtzsche and Jørgensen, along with Dr. John Keen from John Stroger Hospital in Chicago, arguing that mammography screening leads to the diagnosis of breast cancers that would never become clinically evident or lethal if left undiscovered. They take the position that breast screening is a multibillion industry that's protected by a combination of vested economic interests and emotional advocacy groups.

Meanwhile, mammography's proponents, led by Kopans and colleagues Robert Smith, PhD, of the American Cancer Society (ACS) and Dr. Stephen Duffy of Queen Mary, University of London, counter that there is no clinical evidence to support the Cochrane's group's claims that some cancers would "spontaneously disappear" if not treated. Overdiagnosis is a fact of life in all areas of medicine, and women should not be denied access to the life-saving benefits of mammography because of it, they claim.

The commentaries are sure to fuel an already heated debate that has been roaring for at least 10 years, and one that was highlighted by the 2009 controversy over the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's (USPSTF) withdrawal of its recommendation that women ages 40 to 49 receive annual screening. The USPSTF cited overdiagnosis and overtreatment as some of mammography's "harms" that should be weighed against its benefits when considering whether to screen younger women.

Mammography screening: Just say no?

Jørgensen and colleagues pull no punches in their commentary, writing that although breast imagers "prefer to think that their daily activities improve health and save lives ... the average breast imager could be doing more harm than good" (Radiology, September 2011, Vol. 260:3, pp. 621-627).

"Proponents of mammographic screening generally say that the benefit is large and established beyond doubt, that there is little overdiagnosis, and that screening leads to less invasive treatment," Jørgensen et al wrote. "The truth is that the benefit is doubtful, that overdiagnosis is substantial and certain, and that screening increases the number of mastectomies performed."

Is mammography screening effective? Not really, Jørgensen told AuntMinnie.com in an email.

"The decrease in breast cancer mortality over the past 20 years has been largest in young age groups that have not been invited to screening," he said. "Also, the decreases in breast cancer mortality in Europe have not been related to when screening was introduced. This is unequivocal evidence that factors other than screening have been responsible for the decreases in breast cancer mortality. Although these observations cannot exclude a small effect of screening, the expectation that screening would considerably contribute to improved breast cancer survival has been shown to be wrong."

So if screening mammography has no effect on breast cancer mortality, or only a very small effect, there is little or no benefit left to justify screening, "especially now that it has been generally accepted that screening causes substantial overdiagnosis, in addition to the many false positives with their associated psychological harms," Jørgensen said.

Unfortunately, breast cancer has been politicized such that open discussion of its benefits or harms is difficult, Jørgensen believes.

"Breast cancer clearly has a special status [compared to other diseases], based mostly on emotions," he said. "Politicians gain popularity by supporting the fight against a feared disease, [so] despite high human and economical costs, it would take very strong politicians, indeed, to go against screening and subject themselves to easy [accusations of] prioritizing money over women's lives, false as these accusations may be."

Screening advocates have an interest in high compliance levels with screening, and there are economical and professional vested interests that should not be underestimated -- in the U.S., screening produces about $6 billion in annual revenue, just from the mammograms, and both cancer charities and medical societies accept substantial financial support from the screening industry, according to Jørgensen.

"We would advise both women and policymakers to take a look at the conflicts of interest of those that encourage screening while attacking those who advise informed decision-making," he said.

Stop the madness

Taking the pro-mammography position, Kopans, Smith, and Duffy question both the motivations and scientific underpinnings of the Cochrane group's antimammography position in their article (pp. 616-620). They believe that the research coming from the Cochrane group has long been problematic -- so much so that it has regularly been challenged, Kopans told AuntMinnie.com.

"It is unclear who the 'Cochrane group' really is, and how it deserves an association with regard to mammography screening," Kopans said. "One person, Peter Gøtzsche, was 'the group' for many years. He wrote an article in the Lancet in 2001 that was so vigorously challenged that the journal had him rewrite it. Multiple international reviews have pointed out the major scientific weaknesses and violations of trial analysis in his approach. His methods of analysis have been repudiated and discredited by numerous reviews, yet he still is able to get scientifically unsupportable material published."

The authors' understanding of overdiagnosis is misguided, according to Kopans.

"With regard to 'overdiagnosis,' [Jørgensen et al] take disparate pieces of information and try to link them into an argument," he said. "They write as if they do not understand fundamentals such as 'prevalence' and 'incidence' and extrapolate information without actually having direct data. They appear to have no interaction with women with breast cancer. I have been in the field for over 30 years. I have polled my colleagues around the country. There are many women who refuse care, yet none of us has ever seen a breast cancer 'melt away.' If this occurred in 30% of cancers, why has no one seen it?"

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment occur in all aspects of medical care, Kopans said, and doctors seek ways to reduce them. But the potential for overdiagnosis is not a reason to deny women the opportunity to have their lives saved by early detection.

"[Screening opponents] have been allowed to publish scientific nonsense that is given equal credibility to actual science," Kopans said. "Part of the problem is that none of the major medical journals has published the materials that support screening. I and others are, routinely, turned down when we send in material to refute the nonsense that [screening opponents] publish. Until the medical journals stop being guided by their undisclosed biases and permit an accurate analysis of data, the public will continue to be misled and confused."

Contention? Considerable

Pairing essays that address controversial topics has been a feature in Radiology for a number of years, according to journal editor Dr. Herbert Kressel, who commissioned each commentary. Sometimes authors share outlines and drafts during the writing process, but in this case, they did not.

"This subject is so contentious that we thought it best for the groups to work independently," Kressel told AuntMinnie.com. "I think it's likely that neither author will be totally happy with not having the last word."

The debate highlights the disconnect that can exist between medical specialists and epidemiologists. In this case, there's an interesting gap between the radiologist's understanding of cancer and an epidemiologist's understanding, Kressel said.

"Radiologists see a lesion, and even if they don't know whether it's cancer or not, they assume it is and biopsy it," he said. "The Cochrane group is saying that we're biopsying things that have cancer characteristics but probably would not kill. Their observations are based on an epidemiologist's perspective, and there's a gap there between this perspective and radiologists'."

The commentaries may not change minds, but they may give radiologists a better understanding of the issue of overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening, according to Kressel.

"The issue of overdiagnosis is particularly important, and there's been a lot of discussion about it in terms of breast cancer, although the concept applies to a variety of cancers," he said. "It's important for radiologists to understand the dimensions of the conversation and particularly how it relates to breast cancer, so they can be more informed in discussions with colleagues and patients."