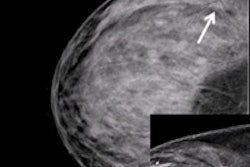

Breast cancer screening programs in Switzerland should be wound down, as screening does not clearly produce more benefits than harms, according to an editorial by two members of the Swiss Medical Board published on 16 April in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The editorial echoes the recommendations made in a report in February by the board, a nongovernmental group that advises government agencies and healthcare service providers. That report has already led to controversy within Europe by breast imagers, who believe the report relies too heavily on controversial studies.

The Swiss Medical Board began reviewing mammography in January 2013, well aware of the controversies swirling around breast screening, wrote Dr. Nikola Biller-Andorno, PhD, from the University of Zurich and Dr. Peter Jüni from the University of Bern.

They became concerned primarily because the ongoing debate was based on reanalyzing the same, predominantly outdated trials; none was initiated in the era of modern breast cancer treatment, Biller-Andorno and Jüni wrote. Also, it wasn't obvious to them that the benefits of mammography screening outweighed the harms.

"The relative risk reduction of approximately 20% in breast cancer mortality associated with mammography that is currently described by most expert panels came at the price of a considerable diagnostic cascade, with repeat mammography, subsequent biopsies, and overdiagnosis of breast cancers -- cancers that would never have become clinically apparent," they wrote.

The researchers cite the recent Canadian National Breast Screening Study as evidence of overdiagnosis (BMJ, 11 February 2014).

The third concern Biller-Andorno and Jüni expressed is the "pronounced discrepancy between women's perceptions of the benefits of mammography screening and the benefits to be expected in reality."

For example, in a telephone survey of random samples of women in the U.S., U.K., Italy, and Switzerland, 717 out of 1,003 women said they believe mammography reduced the risk of breast cancer deaths by at least half, and 723 thought at least 80 deaths would be prevented per 1,000 women who were invited for screening (International Journal of Epidemiology, October 2003, Vol. 32:5, pp. 816-821). In actuality, the relative risk reduction is 20%, and breast cancer screening would prevent one breast cancer death per 1,000 women screened, according to the researchers.

"How can women make an informed decision if they overestimate the benefit of mammography so grossly?" Biller-Andorno and Jüni wrote.

In the February report, the Swiss Medical Board recommended no new systematic mammography screening programs be introduced and that a time limit be placed on existing programs. The board also stipulated that the quality of all forms of mammography screening should be evaluated, and clear and balanced information should be provided to women regarding the benefits and harms of screening.

"It is easy to promote mammography screening if the majority of women believe that it prevents or reduces the risk of getting breast cancer and saves many lives through early detection of aggressive tumors," Biller-Andorno and Jüni wrote. "We would be in favor of mammography screening if these beliefs were valid. Unfortunately they are not, and we believe that women need to be told so."