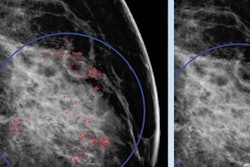

Radiologists who used computer-aided detection (CAD) software to read screening mammography exams had no better accuracy than those who didn't, according to a new study published online Monday in JAMA Internal Medicine. The findings are the latest to cast doubt on the value of breast CAD.

Researchers have been sounding the alarm on mammography CAD almost since the first software application was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998. While CAD for mammography has promised to help radiologists find cancers they might miss, this promise hasn't necessarily been fulfilled, wrote a group from several U.S. institutions.

Add to that the fact that breast CAD costs about $400 million per year in the U.S. -- a lowball estimate since it is based on Medicare reimbursement of $7 per exam, while private insurers pay more like $20 -- and you've got a formula for waste, according to the authors.

"CAD is a technology that does not seem to warrant added compensation beyond coverage of the mammographic examination," they wrote.

Too fast, too soon?

In 2002, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established reimbursement for the technology, sparking rapid uptake in practices across the country. In 2003, 5% of screening mammograms were digital and interpreted with CAD, but by 2012, 83% were digital and read with CAD (JAMA Intern Med, September 28, 2015).

Dr. Constance Lehman, PhD, from Massachusetts General Hospital.

Dr. Constance Lehman, PhD, from Massachusetts General Hospital.Early studies supporting the efficacy of CAD were performed in labs rather than clinical settings and measured the technology's ability to mark cancers on selected mammograms. But the "high sensitivities" reported in those studies did not translate into clinical practice, according to the authors.

"We found higher rates of [ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)] lesions detected with CAD on digital mammography, but no differences in sensitivity for cancer (whether for DCIS or invasive) and no differences in rates of invasive cancers detected," the group wrote. "A meta-analysis in 2008 of 10 studies of CAD applied to screening mammography concluded that CAD significantly increased recall rates with no significant improvement in cancer detection rates compared with readings without CAD."

The case of breast CAD is a classic example of a rushed rollout of new technology, according to lead author Dr. Constance Lehman, PhD, from Massachusetts General Hospital.

"CAD is a story of getting ahead of ourselves, and now we have to back up a bit," she told AuntMinnie.com.

Sensitive and specific

For the current study, Lehman's group compared the accuracy of digital screening mammography read with and without CAD between 2003 and 2009 in 323,973 women. Of the total mammograms, 495,818 were interpreted with CAD and 125,807 were read without it. Breast cancer was identified in 3,159 women.

The mammograms were read by 271 radiologists from 66 U.S. facilities that were part of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC). Of the 271 radiologists, 82 had never used CAD, 82 always used the technology, and 107 sometimes used it. The researchers assessed sensitivity, specificity, cancer detection, and interval cancer rates per 1,000 women, as well as factors such as patient age, breast density, menopausal status, and time since prior mammogram.

They found that the performance of the full set of 271 radiologists interpreting screening mammography was not improved by CAD for any of the metrics assessed, and there was no difference in any of the patient characteristic subgroups. Although there were slight differences in sensitivity, specificity, and cancer detection rate between the technologies, none of the differences were statistically significant, with the exception of CAD's detection of DCIS, which was slightly higher than when CAD wasn't used.

"CAD adds cost but no value to mammography's diagnostic performance," Lehman told AuntMinnie.com.

| Radiologist accuracy with and without breast CAD | ||

| Measure | With CAD | Without CAD |

| Sensitivity | ||

| Overall | 85.3% | 87.3% |

| Invasive cancer | 82.1% | 85% |

| DCIS | 93.2% | 94.3% |

| Specificity | ||

| Overall | 91.6% | 91.4% |

| Cancer detection rate per 1,000 women | ||

| Overall | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| Invasive | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| DCIS | 1.2 | 0.9 |

"If CAD were working well, we would see statistically significant p-values for it, and the only measure we're seeing with that is for detecting DCIS," said co-author Diana Buist, PhD, from the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle. "The fact that these percentages aren't significant supports the point that CAD is not effective."

In fact, CAD decreased sensitivity in the subset of 107 radiologists who interpreted mammograms with the technology and without it (these radiologists worked at various BCSC facilities, some of which had breast CAD and some of which did not). In this group of readers, sensitivity was 83.3% with CAD and 89.6% without it, while specificity was 90.7% with CAD and 89.6% without the technology.

Should we pay?

The study findings illustrate the pitfalls of adopting a new technology before it's been fully tested, Lehman's group believes. New technology needs to go through a thorough testing process -- starting in the laboratory, followed by a reader study and then an academic center -- before being adopted for general practice.

"We're all eager to get new technology out to patients, but it has to go through its paces," Lehman said. "CAD was rolled out and approved for reimbursement before this could happen."

The current study calls into question whether society should continue to pay for CAD use, wrote Dr. Joshua Fenton of the University of California, Davis, in an accompanying commentary also published online. Fenton has written several articles on CAD, most critical of the technology.

"Payments for ineffective services like CAD combine to bloat our healthcare economy," he wrote. "Congress should therefore rescind the Medicare benefit for CAD use. If we could curtail use of many similarly ineffective tests and interventions, we could significantly reduce U.S. healthcare expenditures while augmenting resources for effective care. ... The lesson of CAD is that broad societal investment in new medical technologies should occur only after large-sample evaluations prove their real-world effectiveness and justify their costs."

In any case, radiologists should be more vigilant when it comes to new technology, Lehman said.

"I've been inspired by the American College of Radiology, which is asking all of us to really own our profession and put our patients first," she said. "It's our responsibility to bring technology into our practices that's truly beneficial -- and to make sure any new advances are rigorously tested before that happens."