What if you could make it easier to find breast cancer in your patients, just by having them take a pill? That's the tantalizing idea behind an animal study presented by University of Michigan researchers on March 15 at the American Chemical Society meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Greg Thurber, PhD, and colleagues have developed a near-infrared imaging agent that can be delivered orally in pill form. The agent binds to cancer cells or blood vessels unique to tumors, releasing a dye that fluoresces under near-infrared light.

While a number of challenges remain, the researchers believe the pill could offer a functional imaging component as a complement to an anatomical modality such as ultrasound to better identify and characterize breast cancer.

Targeted probe

The group's research is designed to address one of the big limitations of mammography: namely, that it's an anatomical modality that doesn't acquire functional information that could denote malignancy.

"The problem with mammography is that you're taking a picture of the breast tissue, and from that trying to identify which lumps or lesions are malignant," Thurber said in a press conference about the research. "What we're trying to do is develop a molecular probe that specifically binds to cancerous cells."

The pill would be taken a day or two before the patient arrived at the doctor's office, allowing for absorption of the targeting agent via the digestive tract. The physician would then pass an infrared light over the patient to screen for breast cancer, according to Thurber.

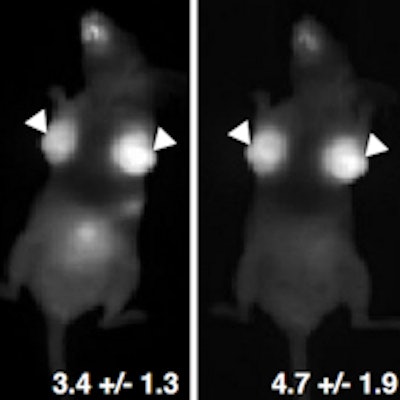

When he and his colleagues tested the agent on mice, they found that 50% to 60% of the agent was absorbed into the bloodstream and attached specifically to cancer cells. The fluorescent signal from the tumor was stronger than the signal from the surrounding tissue, according to the researchers.

A scan of one of the mice with orthotopic breast cancer tumors. Image courtesy of Dr. Greg Thurber, PhD.

A scan of one of the mice with orthotopic breast cancer tumors. Image courtesy of Dr. Greg Thurber, PhD."We injected human breast tissue cells into the mammary fat pads of the mice, and over one to two days saw a high uptake of the fluorophore in cancerous tissue," Thurber said.

The compound is water-soluble, and it gets filtered by the kidneys and excreted in the urine, Thurber said. The dye is already in use in Europe for other clinical applications, which could help speed its approval for this particular use in the U.S.

Going deeper

One limitation of the technology is that at this light wavelength, tumors can only be detected at a depth of 1 cm to 2 cm, according to Thurber. This means that currently the agent could only be used for imaging disease that is close to the surface of the skin. However, pairing this molecular technology with ultrasound could make it more effective, he said.

"Ultrasound is a safe imaging method, but like mammography, it doesn't offer any molecular information," he said. "Pairing near-infrared imaging with ultrasound could be an effective and noninvasive way of accurately identifying malignant lesions."

If Thurber and colleagues are successful in formulating an oral imaging agent for clinical use, its high image contrast could be helpful for women with dense breast tissue, the group said. The researchers are trying to design the agent to specifically seek out aggressive tumors, which could help clinicians distinguish them from slow-growing cancers such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

"We're very interested in accurately diagnosing disease at an early stage," Thurber said. "We hope this technology could offer a way to make breast cancer screening more efficient."