In yet another salvo in the ongoing battle over screening mammography, research published in the October 13 New England Journal of Medicine claims that the reduction in breast cancer mortality after the advent of screening mammography is primarily a result of improved systemic therapy, not earlier detection.

In fact, improved treatment is responsible for at least two-thirds of the reduction in breast cancer mortality since population-based screening mammography was implemented, wrote the group led by Dr. H. Gilbert Welch of Dartmouth College. Using data from the U.S. National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, the researchers analyzed size-specific incidence of breast cancer among women 40 and older to come to this conclusion (NEJM, October 13, 2016, Vol. 375:15, pp. 1438-1447).

The study follows earlier work published in the NEJM in 2012 from Welch and Dr. Archie Bleyer of Oregon Health and Science University, which concluded that overdiagnosis accounted for nearly a third of all newly diagnosed breast cancers.

As with the 2012 paper, this study has prompted an immediate response, both within organized radiology and among prominent breast radiologists who have criticized Welch's work in the past.

Screening's effectiveness

In their 2012 paper, Welch and Bleyer noted a 28% drop in deaths from breast cancer over 30 years, but they said this was a sign of overdiagnosis because women who were not exposed to screening had a greater reduction in mortality. The current paper tries to hone in on the effectiveness of screening by looking at the size of cancers being detected over the study period, on the theory that a shift toward smaller tumors could be a sign that screening was working.

Welch's group used SEER data from 1975 to 2012 to calculate the size of tumors in women age 40 or older with breast cancer. The researchers analyzed the size of cancers in women who died to calculate a size-specific cancer fatality rate for two time periods: a baseline period before widespread implementation of screening mammography (1975-1979) and a more recent period for which 10 years of follow-up data were available (2000-2002).

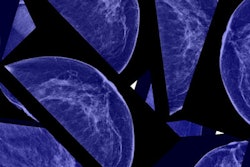

After the advent of screening mammography, the proportion of small invasive tumors detected (those smaller than 2 cm or ductal carcinoma in situ) increased from 36% to 68%, while the proportion of large invasive cancers (those at least 2 cm) decreased from 64% to 32%, Welch and colleagues found.

They wrote, however, that the trend was less the result of a substantial decrease in the incidence of large tumors (30 fewer cases of cancer were observed per 100,000 women in the period after the advent of screening than in the period before screening) and more the result of a marked increase in the detection of small tumors (with 162 more cases of cancer observed per 100,000 women).

"Assuming that the underlying disease burden was stable, only 30 of the 162 additional small tumors per 100,000 women that were diagnosed were expected to progress to become large, which implied that the remaining 132 cases of cancer ... were overdiagnosed," the researchers wrote. "The potential of screening to lower breast cancer mortality is reflected in the declining incidence of larger tumors. However ... the decline in the size-specific case fatality rate suggests that improved treatment was responsible for at least two-thirds of the reduction in breast cancer mortality."

Faulty assumption?

But that assumption about underlying disease burden is faulty, according to Dr. Daniel Kopans of Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital, who has authored a response to the paper.

"Their thesis is based on their incorrect guess that the incidence of invasive breast cancer was not increasing prior to screening," he said. "In fact, it had been increasing by 1% to 1.3% per year since 1940. If they did the analysis using the proper baseline, they would find that not only is there little if any overdiagnosis of invasive cancers, but, contrary to their claim, there has been a marked decline in advanced cancers over the time period -- and this is in direct relationship to the shift to smaller cancers due to screening."

Welch's team should also re-examine the size-specific case fatality rate numbers, and present them by actual sizes, rather than ranges, Kopans said.

"A shift in detection from 2 cm to 2.9 cm will have a major effect on deaths, as will a shift from 1 cm -- almost all cured -- to 1.9 cm, where lives are lost," he said.

The study is using the size-specific precision that was available in SEER in 1975, Welch told AuntMinnie.com.

"More precision becomes available in the early 1980s," he said. "In fact, what change there has been has been toward larger, not smaller, tumors. Among 1 cm to 1.9 cm tumors, the average size has moved from 1.37 to 1.38 cm, while among 2 cm to 2.9 cm tumors, the average size has moved from 2.25 to 2.29 cm. The bottom line is that the size distribution within categories is essentially stable."

Mixed results?

The introduction of screening mammography has had mixed results, Welch's group concluded. From the SEER data, a modest decrease in the incidence of large tumors can be observed, which suggests that screening has had the desired effect of advancing the time of diagnosis of some tumors destined to become large. But the larger increase in the incidence of small tumors suggests that screening has contributed to overdiagnosis.

"The magnitude of the imbalance indicates that women were considerably more likely to have tumors that were overdiagnosed than to have earlier detection of a tumor that was destined to become large," Welch and colleagues wrote.

It's just not true, Kopans said.

"The authors have clouded their analysis of the case fatality rates to claim that most of the decline in deaths is due to improvements of therapy," he said. "Yes, therapy has improved, but oncologists know that the most lives are saved by annual screening starting at the age of 40."

Organized radiology groups such as the American College of Radiology (ACR) echo Kopans' arguments against the paper. The numerical data used in the study actually show that mammography screening catches more cancers early and reduces the number of women with cancers of advanced size.

"The data do not support the authors' conclusion that improved therapy is more key to breast cancer survival than mammography screening," the ACR said in a statement. "Nor does the data support that mammography use leads to rampant overdiagnosis. The ... SEER database used by the authors does not provide the detailed information needed to support such claims ... and the ... assumption on which the conclusions are based is contradicted by the primary author's previous papers and well-established research."

Double-edged sword?

How will this debate over mammography screening affect physicians -- and women? The issue of overdiagnosis has become more familiar to a broader group of doctors, Welch told AuntMinnie.com.

"Physicians' understanding of cancer is changing, and while for a long time screening has been considered a kind of no-brainer, now the medical community is considering that it can be a double-edged sword," he said.

As for how conflicting studies regarding mammography's efficacy affect women's understanding of the benefits or harms of screening, opening up the discussion is a good thing, according to Welch.

"It's a mistake to consider mammography screening a public health imperative," he said. "Rather, it's a choice, and there's no single right answer. Women who feel positive about mammography should continue, but those who have felt pushed into it, or who have had negative experiences with false positives, should feel equally good about not doing it."