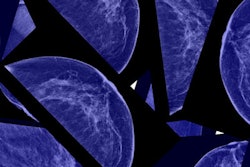

Continuing a campaign going back to at least 2000, researchers from the Nordic Cochrane Centre in Copenhagen take aim at screening mammography in a January 10 article in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The group claims that breast screening doesn't reduce the incidence of advanced tumors, and that one-third of tumors detected actually represent overdiagnosis.

A team led by Dr. Karsten Juhl Jørgensen wanted to determine the extent to which mammography resulted in overdiagnosis, or the detection of cancers that would never pose a threat to the health of women being screened (Ann Int Med, January 10, 2017). Cochrane researchers for decades have been harsh critics of breast screening, which they believe mostly detects indolent cancers and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). This week's study is no exception.

"Seventeen years of organized breast screening in Denmark has not measurably reduced the incidence of advanced tumors but has markedly increased the incidence of nonadvanced tumors and DCIS," the authors wrote. "These findings raise questions about whether screening provides the promised benefits of reduced breast cancer mortality, less invasive treatment, and reduced disease burden."

However, as with previous research from the Nordic Cochrane Centre, the study has prompted an immediate response among prominent breast radiologists who have criticized the center's work in the past.

Effective screening?

Effective breast cancer screening should detect early-stage cancer and prevent advanced disease. However, overdiagnosis occurs when mammography detects small tumors that may never affect the patient's health during a lifetime, Jørgensen and colleagues wrote. The researchers emphasized that "the problem with overdiagnosis is that it exposes patients to the potential harms of treatment, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, without a clinical benefit."

Jørgensen's group therefore sought to assess the association between screening and the size of detected tumors and to estimate overdiagnosis using data taken from two Danish cancer registries. In Denmark, women are screened biennially between the ages of 50 and 69.

To determine trends in overdiagnosis, the researchers used two approaches. In the first, they measured the incidence rates of advanced tumors (larger than 20 mm) and nonadvanced tumors (20 mm or smaller) in before and after periods in areas that had screening and in areas that didn't have screening. The number of overdiagnosed tumors was the difference between the number of tumors in the screening areas and the areas without screening.

In the second approach, they estimated trends in overdiagnosis by comparing the incidence of advanced tumors in women ages 50 to 84 in areas with and without screening, as well as comparing the incidence of nonadvanced tumors in women ages 35 to 49, 50 to 69, and 70 to 84 in screening and nonscreening areas. Jørgensen's team defined the screening area as Copenhagen, Funen, and Frederiksberg; the nonscreening area was the rest of Denmark.

Using the first approach, the group found that 271 invasive breast cancer tumors and 179 DCIS lesions were overdiagnosed in 2010, for a rate of 24.4% for invasive tumors and DCIS combined and 14.7% for invasive tumors only. Using the second approach, 711 invasive tumors and 180 cases of DCIS were overdiagnosed in 2010, for a rate of 48.3% for both invasive cancer and DCIS and 38.6% for invasive tumors only.

"When our approach accounted for regional difference in women younger than the screening age, our estimate of overdiagnosis (including DCIS) was 48.3%," the group wrote. "Therefore, one in every three breast tumors detected in women aged 50 to 69 years was probably overdiagnosed."

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Otis Brawley of the American Cancer Society emphasized the dangers of overdiagnosis by comparing it to racial profiling.

"If the lesion fits the profile of something that killed people in the past, the natural inclination today is to assume that the lesion will grow, spread, and eventually kill," he wrote. "However, some of these lesions may be genomically predetermined to grow no further and may even regress. In many respects, considering all small breast lesions to be deadly and aggressive types of cancer is the pathologic equivalent of racial profiling."

Intentional obfuscation?

Advocates for breast screening are critical of the paper, as they have been of past work from the Nordic Cochrane Centre, dating back to 2000. Indeed, study co-author Dr. Peter Gøtzsche in 2012 published a book titled Mammography Screening: Truth, Lies and Controversy that offered an indictment of breast screening and suggested that the best way to decrease breast cancer risk is to avoid being screened.

The science behind the current study is deliberately confusing and draws conclusions from faulty data, according to Dr. Daniel Kopans of Massachusetts General Hospital.

"The paper is far more complex than is needed, and this simply clouds the underlying premise," Kopans told AuntMinnie.com via email. "The authors claim that there was little reduction in women with advanced cancers when they compared data -- not women -- from 'screening areas' in Denmark to those in 'nonscreening areas' as an indication that screening was finding 'fake' cancers. This is the fundamental problem with this paper: It does not provide direct information as to which women were participating in screening (nor at what frequency) and which women were not participating in screening. No one has any idea as to whether or not women in the 'nonscreening' areas had the same underlying risks, and there are no data on which women were being screened outside the program."

There's no reason why the study authors shouldn't look at actual women, their screening behavior, and the results from screening (or not participating in screening), according to Kopans.

"This repeated use of methods of obfuscation should be discouraged and direct data should be required," he said.