When radiologists think about mammography, transgender patients may not first come to mind. But transgender women and men are not immune to breast cancer and other health concerns. How often do these patients need mammograms? And what are the best screening practices?

Although the answers to these questions aren't always clear-cut, an article in the current issue of Radiographics outlined what radiologists need to know about breast imaging for the transgender population.

"At our institution, we have found that increasing numbers of transgender individuals are coming to our clinics," lead author Dr. Ujas Parikh, from the New York University School of Medicine, told AuntMinnie.com. "Breast imaging is deeply rooted in delivering evidence-based medical care, but this is difficult to achieve when we have limited data on breast cancer risk and appropriate imaging in this population."

Dr. Ujas Parikh.

Dr. Ujas Parikh.

The term transgender describes people whose internal and external gender identity do not match the sex assigned to them at birth. In contrast, cisgender describes people whose internal and external gender identity are the same as the gender assigned at birth.

An estimated 1.2 million transgender people live in the U.S., and more transgender individuals are choosing to alter their physical appearance through hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery. As a result, it's increasingly likely that radiologists will encounter an individual from this population.

"Radiologists need to be aware of the unique needs of the transgender population," Dr. Parikh said. "We need to deliver appropriate care to a population that is gaining in visibility and will be more ever-present in our clinics."Transgender women

Many transgender women use estrogen and antiandrogen medications to appear more feminine, the authors noted (Radiographics, January-February 2020, Vol. 40:1, pp. 13-27). The associated hormonal changes can lead to breast growth that peaks two to three years after the start of hormone therapy.

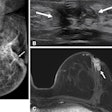

Transgender women who take high levels of estrogen develop breast tissue that appears radiographically similar to the tissue of cisgender women. This includes breast ducts, lobules, and acini, as well as the potential of developing cysts, fibroadenomas, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia, and other benign findings. In addition, transgender women can have a range of breast densities, and one study found that about 60% have dense or very dense breast tissue.

More cases of breast cancer in transgender women are being reported in the scientific literature, but the breast cancer risk for transgender women on hormone therapy is unknown, according to Parikh and colleagues. There is also no unified recommendation for mammography for transgender women.

Many advocacy organizations recommend breast cancer screening every one to two years starting at age 50, especially if a patient has been using hormone therapy for more than five years. Some guidelines recommend early screening if the patient has other breast cancer risk factors, including testing positive for the breast cancer gene (BRCA). If a radiological or palpable finding is suspicious, the recommendations are the same as for cisgender women, the authors noted.

In addition, some transgender women have what is colloquially known as top surgery to increase their breast size and/or fullness. In some case reports, transgender women have developed anaplastic large-cell lymphoma associated with breast implants. Silicone implants can also rupture, something that should be looked for with mammography.

Finally, some transgender women inject silicone, mineral oil, liquid paraffin, and other particles and fillers into their breast tissue despite this practice being banned in the U.S. Contrast-enhanced MRI may be beneficial to evaluate this subset of patients.

Transgender men

Transgender men who choose to participate in hormone therapy typically take testosterone, and some may also use progestins and medication to prevent alopecia. Long-term testosterone use is associated with an increase in breast connective tissue and a reduction in breast glandular tissue. It is unclear whether testosterone affects breast cancer risk, Parikh and colleagues wrote.

Some transgender men also have top surgery to remove breast tissue. Unlike a mastectomy, top surgery sometimes includes chest contouring and nipple grafting to appear like a male breast. In some cases, surgeons request preoperative mammography before performing top surgery for transgender men.

There is not enough data to determine breast cancer risk for transgender men with top surgery, although some breast cancer cases have been reported, the authors noted. Ultrasound and MRI may be helpful to evaluate transgender men who have a palpable concern but not enough breast tissue for mammography. For transgender men who have not had top surgery, screening and mammography recommendations are the same as for cisgender women.

"Although evidence-based breast cancer care in the transgender population is in its infancy, it’s important to recognize that there are multiple factors to keep in mind when assessing whether a transgender patient should be screened for breast cancer," Dr. Parikh said. "While there is a need to establish clear evidence-based screening guidelines for this population, it also must be recognized that not every transgender patient has the same breast imaging needs."