Black women had high rates of health conditions linked to worse breast cancer outcomes in a study published on December 7 in Cancer. These trends could be contributing to worse breast cancer outcomes for Black women despite years of better treatment options and widespread screening mammography.

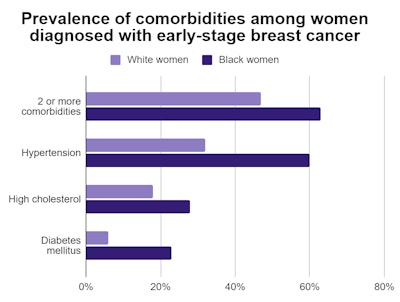

The retrospective study, led by Kirsten Nyrop, PhD, looked at differences among 548 Black and white women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Black patients had higher rates of hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes at diagnosis, even after the authors adjusted for age and body mass index (BMI) score.

Both obesity and HR+ breast cancers have been rising in the U.S. for decades. While new treatments and widespread screening mammography have resulted in better breast cancer outcomes overall, Black women are still more likely to die from breast cancer than white women.

One study cited by Nyrop and colleagues found that Black women with highly treatable HR+ breast cancer were almost 4.5 times more likely to die from breast cancer than white women after adjusting for stage, grade, and treatment type. Some of this mortality gap can be explained by known factors, such as insurance status, but the authors wondered whether obesity rates also contributed to some of the differences in outcomes.

"Early breast cancer is highly treatable, and survival rates have improved steadily due to treatment advances and early detection through mammograms," stated Nyrop, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in a press release. "However, the high rates of obesity, overall comorbidities, and obesity-related comorbidities observed among women with early breast cancer -- especially among Black women -- can contribute to disparities in overall survival of these patients."

In the new study, Black women were significantly more likely than white women to have two or more comorbidities at breast cancer diagnosis. Even after adjusting for age and BMI score, Black patients still had a 1.45-times greater prevalence of hypertension, 1.43-times greater prevalence of high cholesterol, and 1.44-times greater prevalence of diabetes.

The authors also analyzed only women with HR+ and HER2- breast cancers, which result in excellent mortality outcomes. In this cohort, Black women had almost twice the prevalence of two or more obesity-related comorbidities and three times the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. They also had 1.4-times the prevalence of hypertension.

"The study by Nyrop et al has not only highlighted the importance of recognizing racial disparities among obesity trends, but stressed the need to address comorbidities early in breast cancer management for patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds," wrote Drs. Caitlin Taylor and Jane Lowe Meisel from Winship Cancer Institute at Emory University in Atlanta in an accompanying editorial.

"Given the known prognostic implications of obesity and obesity-related complications among patients with breast cancer, these differences in prevalence are significant and undoubtedly contribute to the overall disparities noted in breast cancer outcomes among Black women," wrote Taylor and Meisel.

The findings reinforce the importance of managing comorbidities for women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Clinicians should also take into account larger trends when interpreting the findings, Nyrop added.

"Findings from this study need to be considered within the larger context of the cancer-obesity link and the disparate impact of the obesity epidemic on communities of color in the United States," she stated. "As the COVID-19 pandemic has glaringly underscored, there is an urgent need to address the systemic and socioeconomic aspects of obesity that disproportionately affect minority communities in the U.S. if we are to reverse health disparities."