Ultrasound can help identify the features that could indicate less aggressive ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) on breast exams, possibly helping women avoid surgery, according to research published February 15 in Radiology.

Researchers led by Si Eun Lee, PhD, from Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea, developed a clinical model that they wrote could help determine if nonsurgical approaches can be used to treat this kind of DCIS in patients.

"We believe our model can be used before surgery to help clinicians decisively select lesions likely to be low nuclear grade DCIS," Lee and colleagues wrote.

DCIS makes up about 25% of newly diagnosed breast cancers. In recent years, more DCIS lesions have been detected due to more widespread breast cancer screening.

Surgery followed by adjuvant therapy is the standard treatment regimen. However, since many DCIS cases don't become invasive breast cancer, researchers have questioned whether they are overdiagnosed and if surgery is needed. Aggressively treating DCIS may not reduce breast cancer mortality and could cause complications in women with low-risk DCIS that won't become invasive, even without surgery, the researchers wrote.

But not all DCIS cases develop equally. High-nuclear-grade DCIS, which is more biologically aggressive, is linked to the development of high-nuclear-grade invasive cancer. Previous research suggests that the survival rates of women are similar whether low-nuclear-grade DCIS is surgically removed or not.

"Because the nuclear grade of DCIS is a proven predictor of poor prognosis, several prospective randomized trials are now focusing on patients with low nuclear grade or intermediate nuclear grade DCIS to undergo surveillance without surgery," the researchers wrote.

The Lee team wanted to develop a clinical model for use prior to surgery to identify low-nuclear-grade DCIS. They also wanted to look at factors linked to low-nuclear-grade DCIS at biopsy that was not upgraded to intermediate to high-nuclear-grade DCIS at surgery.

The researchers looked at data from 470 women with a median age of 50 years. They also looked at 477 pure DCIS lesions at surgical histopathologic evaluation collected between January 2010 and December 2015.

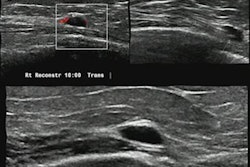

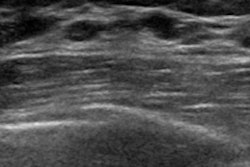

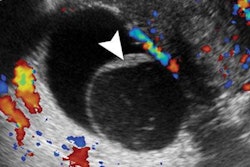

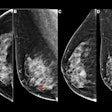

The women were divided into two sets, 330 for a training set and 147 for a validation set. The team reviewed ultrasound and mammography features. The clinical model included lesions that presented as a mass at ultrasound without microcalcification and no comedonecrosis at biopsy. This was used to identify low-nuclear-grade DCIS.

The study authors found this model had a high area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) curve of 0.97 in the validation set. They also found that the upgrade rate of low-nuclear-grade DCIS at biopsy was 38.8% (50 of 129).

The team wrote that low-nuclear-grade DCIS lesions manifesting as a mass at ultrasound without microcalcifications at mammography and no comedonecrosis at biopsy were not upgraded at surgery.

The group also added that the positivity of Ki-67, a nuclear protein that serves as an indicator for assessing biopsies from cancer patients, was inversely associated with constant low-nuclear-grade DCIS (p = 0.005).

"If low nuclear grade DCIS at biopsy was positive for Ki-67, the lesion could be reconsidered for possible upgrade to intermediate or high nuclear grade," the authors wrote.

The team also wrote that they believe there is room to better prognosticate DCIS in the future by using MRI features. This is because of angiogenesis being an "important factor" for grading DCIS, which can be depicted only with MRI.