Women with multiple sclerosis (MS) are less likely to have breast cancers detected through screening mammography than women without MS, according to Canadian research published April 27 in Neurology.

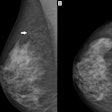

A team led by Patti Groome, PhD, from Queen's University in Ontario found that after adjusting for age, diagnosis year, and income, the odds of breast cancer being detected through routine screening mammography was 32% lower in women with MS. The group also found that people with MS are more likely to have colorectal cancers detected at an early stage than those without MS.

"Studies in other populations suggest women with physical limitations, such as difficulty standing unaided, are less likely to get mammography screening," corresponding author Ruth Ann Marrie, PhD, told AuntMinnie.com. "Specific strategies to address these physical barriers need to be addressed."

Current evidence shows that people living with MS, a debilitating autoimmune disease of the nerves, have compromised access to cancer screening. Women with MS who have mobility impairments are less likely to undergo preventive cancer screening than women with MS without mobility impairments, research also says.

The authors wrote that longer diagnostic intervals might occur for these patients if cancer symptoms were mistakenly attributed to MS or if cancer symptoms were less significant than other competing health problems.

Groome et al wanted to evaluate how MS and cancer patients go through the diagnostic process by documenting three interconnected parts. These include screening versus symptomatic detection, cancer stage, and length of time for a diagnosis to be reached. They then compared the experiences of both respective patient populations, looking separately at breast and colorectal cancer to see whether findings were consistent across cancer types.

The team looked at data from 351 patients with both MS and breast cancer, 1,404 matched patients with breast cancer without MS, 54 patients with MS and colorectal cancer, and 216 matched patients with colorectal cancer without MS.

The researchers found that MS was associated with fewer screen-detected cancers in breast cancer, with an odds ratio of 0.68, and possibly colorectal cancer with an odds ratio of 0.52. They also found that MS was not linked to differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis, with an odds ratio of 0.81 for stage I cancer. However, they also found that MS was associated with greater odds of stage I colorectal cancer (odds ratio, 2.11).

Screening mammography detected breast cancer in patients with MS 29.3% of the time, compared with 37.7% of the time in patients without MS (p = 0.004).

The team also found that the median length of the diagnostic interval did not vary between people with and without MS in either cancer cohorts. The median interval in breast cancer patients with MS was 35 days, compared with the interval of 34 days in patients without MS.

The study authors wrote that based on these findings, as well as other research, compromised processes for diagnosing cancer become visible through fewer screen-detected cancers. They called for disparities in care for MS patients to be addressed.

"MS-related disability may prevent people from getting mammograms and colonoscopies," Groome and colleagues wrote. "Understanding the pathways to earlier detection in both cancers is critical to developing and planning interventions to ameliorate outcomes for people with MS and cancer."

Marrie told AuntMinnie.com that the team is interested in learning more about treatment following cancer diagnosis, as well as barriers to cancer screening.