The use of 3D imaging in trauma applications is escalating rapidly, helping to improve the process of surgical planning, and in some cases eliminating or reducing the extent of invasive surgeries. The technology is also stimulating face-to-face collaboration between radiologists and surgeons.

The installation of 32-, 40- and 64-slice multidetector-row CT (MDCT) scanners by hospitals is increasing their availability to trauma patients. Because MDCT images have sharper resolution and better reformatting capabilities, they are replacing conventional CT scans and general radiographic imaging that had been routinely ordered for trauma patients.

Steady improvement in 3D imaging software is the factor most attributed to the increased use of 3D imaging in trauma, according to researchers and clinicians contacted by AuntMinnie.com. Multiplanar reconstruction has become highly automated; 3D reconstruction has been simplified, enabling users to create detailed images rapidly within a five- to 10-minute period using either a dedicated 3D workstation or software installed on a PACS diagnostic workstation. It's also much easier for radiologists to become proficient with current versions of 3D software.

3D trauma imaging is primarily used for skeletal injuries, facial trauma requiring oral maxillofacial surgery, vascular trauma, and trauma involving the diaphragm. It's become a vitally important tool to physicians and surgeons staging emergency treatment and surgical planning. On the downside, the technology rarely helps radiologists make a better diagnosis, and it adds to workloads.

Surgical collaboration

Surgeons can relate better to an anatomical image showing a 3D perspective of injuries, rather than trying to visualize the injury by looking at a series of CT slices on an axial plane. In many cases, radiologists find explaining the scope of an injury in detail easier with a 3D anatomical model, said Dr. James Jelinek, chairman of radiology at Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC.

"Radiologists do not get much benefit from 3D imaging because it is not their job to think about how to put pieces of anatomy back together," Jelinek said. "Orthopedic surgeons, however, greatly value and request 3D images because it enables them to do better surgical planning for pelvic, shoulder, and spine fractures, particularly as this relates to selection and placement of screws and plates."

3D trauma imaging is also helping stimulate face-to-face professional consultation by radiologists with surgeons and emergency department physicians. Both the creators and users recognize that the creation of 3D images for trauma applications may most effectively be done as a collaborative process by the surgeon and radiologist who has already made a diagnosis from axial images.

Images that help surgeons most are typically created in real-time, with the radiologist and surgeon sitting together in front of a workstation. In this manner, as the surgeon observes the images being created, he or she can explain the exact orientation and other features needed. This type of collaboration is bucking the growing trend of decreased communication between radiologists and referring physicians after PACS implementation and images become widely and immediately available.

At the University of Chicago Hospitals (UCH) in Illinois, the more routine 3D images are immediately created by either technologists or radiologists based on the radiology department's established protocols, said Dr. Michael Vannier, a professor of radiology. These 3D images are added to the CT procedure image folder already online in the PACS as soon as they are completed. They are then positioned as the first image within a folder for immediate access by emergency physicians.

"One of the reasons that my beeper goes off is that an emergency physician or surgeon is asking where his/her 3D images are when opening a study on a PACS," Vannier said. "He/she also may be asking if I can create a different image, and if he can come over to the department to work with me to get exactly what he needs."

As with many Level I trauma centers, UCH has 3D imaging service available on a 24/7 basis.

Workload tradeoffs?

At the University of Maryland's R. Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center in Baltimore, 3D imaging has become part of the routine workload, just like the steadily increasing number of exams having very large number of images, according to Dr. Stuart Mirvis, a professor of diagnostic radiology and director of emergency radiology/trauma radiology. The trauma center averages 7,000 annual visits, and is staffed by five trauma radiology specialists.

Mirvis noted that very few research papers have been published that scientifically measure the value of 3D anatomical imaging to surgeons, or measure outcome differences in patient care. He also questions the feasibility and ethicality of such a study.

"Its impact may not be measurable, but our surgeons say 3D imaging for specific applications is of immeasurable value to them," he said.

One of the greatest benefits of 3D imaging is the ability to visualize the extent of an injury, particularly a vascular one, prior to initiating surgery, said Dr. Kathirkama Shanmuganathan, a professor of diagnostic radiology at the trauma center. For example, the technology can help surgeons identify the existence and precise location of a hole in the diaphragm, enabling them to repair it with the least invasive surgery necessary.

Another frequent use of 3D imaging is to display the extent of injuries to branches within the splenic parenchyma. 3D helps emergency physicians with the management and planned treatment of injuries to the spleen.

Shanmuganathan finds that 3D imaging even provides value in helping him diagnose significant lower thoracic and upper abdominal injuries.

"The diaphragm is a tough structure and a complex anatomy," he said. "To appreciate all of it in the axial plane is not easy. It is possible to miss subtle diaphragmatic injuries on axial images. Having the reformatted images helps me better identify penetrating trauma where the injuries are going to be very small than by axial images alone."

3D is of greatest value to radiologists when displaying injuries to what are normally complex anatomic structures, said Dr. Clint Sliker, an assistant professor of diagnostic radiology and member of the trauma radiology section. Evaluations of these structures can be complicated by many small displaced fragments.

"3D imaging helps me get a global look at what is going on, and then I can go back to review the more detailed traditional thin-slice axial and multiplanar images," he said. "As an example, for a small number of acetabular and facial injuries, a fracture may be seen clearly only on a 3D view because it is running in a complex plane that standard views do not display."

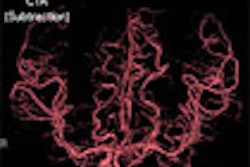

3D imaging of both CT and MRI benefits patients with life-threatening aneurysms. 3D visualization of cerebral vasculature from CT angiography and 3D views of MRI cortical surface and underlying tissues, with optional functional MRI fused with 3D anatomical display, enables neurosurgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston to plan procedures to spare crucial cortical areas. This also may reduce operating room time and improve patient care.

MDCT imaging and 3D reconstruction can speed treatment of the trauma patient. For example, when patients with facial trauma were admitted to the emergency department at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland several years ago, they received a head CT and C-spine and lateral radiographs. Once the maxillofacial surgeons became involved, they would typically request a CT of the face and additional radiographic imaging, said Dr. Jon Bradrick, director of the division of oral and maxillofacial surgery and an associate professor at Cleveland's Case Western Reserve University.

"64-slice MDCT provides one-stop shopping; enough images can be acquired to meet the needs of all specialists without requiring the patient to have additional time-consuming imaging," Bradrick said.

Washington Hospital Center reports a reduction in the number of patients automatically sent for interventional radiography and a reduction in some surgeries. An arteriogram used to automatically be ordered for patients with a penetrating injury to the head or neck. Now 2D and 3D reconstructions are being used to look for hematomas, or arterial or venous injury. Similarly, patients with lacerations to the liver or spleen who are stable without a huge amount of change on CT are observed rather than sent directly to an operating suite.

Maxillofacial surgery

At MetroHealth Medical Center, any patient with trauma that involves facial bones routinely has MDCT scans with 3D reconstruction.

"MDCT has revolutionized our diagnosis of patient trauma," Bradrick said. "The level of detail in these images and the 3D reconstructions allow us to better diagnose fractures and view their orientations. We realize today that when we were limited to general radiography and eight- and 16-slice scanners we missed a significant amount of trauma because we couldn't see it."

Condyle fractures of the mandible represent an excellent example of significant improvement in both diagnosis and surgical planning to repair them. 3D imaging displays a good orientation and location of fractures of an upper jaw split into two or three pieces, and shows the geometry of tiny fractures in the orbital floor area or nasal bones of the sinus cavities.

3D CT imaging also facilitates surgical planning by enabling maxillofacial surgeons to make accurate measurements of landmarks for the puncture of joint spaces in the jaw joint area. Bradrick said that previously he had to guess using his fingers to touch a patient's face.

Another example of how patient treatment can be intangibly improved with 3D reconstruction was seen in a MetroHealth case of a patient who had windshield glass inside his trachea. The glass could be easily seen on chest CTs, and ENT surgeons were planning to do a bronchoscopy to remove it, Bradrick said.

Creating a virtual bronchoscopy enabled MetroHealth's ENT surgeons to see exactly how they could navigate down the trachea, the dimensions of the glass fragments, and their position inside the trachea. Bradrick said that having this information in advance was beneficial to both the surgeons and the patient.

Bradrick said he trains his residents in how to do 3D reconstructions because he feels that it is important for surgeons starting their careers to have this knowledge and skill.

Pitfalls and caveats

Among the pitfalls of the technology, neck braces and backboards may be difficult to remove when sculpting in 3D. Volume averaging may create bone fractures, especially in areas of the skull that has thin bone with air on one side, such as the thin bone around the orbit.

Motion or metal can create artifacts that look like a form of pathology or an injury. In addition, streak artifacts that look like an injury within a blood vessel may be occur as a result of dental work. Sliker emphasized that a radiologist should always rely on traditional axial views, and never evaluate 3D images in isolation.

Because each 3D imaging application has specific strengths, most facilities have more than one 3D program available. Radiologists predict that 3D software will become homogenous in time.

PACS workstations do not yet have the full capabilities and processing power of dedicated 3D workstations, although radiologists like the ability to create 3D images at their PACS diagnostic workstations. PACS architecture and the network on which the system runs may not be able to manage movement of large amounts of data. Planning for the efficient management of 3D imaging used within a trauma setting may require changes to the PACS infrastructure.

"No matter what, there's no going backward -- 3D imaging is here to stay," Vannier said.

By Cynthia Keen

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 24, 2006

Related Reading

3D brings opportunities to sonographers, August 4, 2006

2D, 3D primary VC have their own advantages, July 28, 2006

Part I: Medical image processing has room to grow, July 4, 2006

3D lab efficiency may depend on who's in control, June 22, 2006

Technologists take advantage of 3D opportunity, April 25, 2006

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com