Cinematic rendering is capable of enhancing the visualization of CT scans. But does it provide diagnostic value beyond standard imaging techniques? The answer was yes for the interpretation of a complex aortic scenario detailed in a new study published in Emergency Radiology.

In the case report, senior author Dr. Elliot Fishman and colleagues from Johns Hopkins University used cinematic-rendered images to clarify an irregularity found in a patient's aorta after an acute traumatic injury. The exquisite detail of the images helped confirm a diagnosis of ductus diverticulum -- ruling out the initial suspicion of acute aortic injury and ultimately avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures (Emerg Radiol, January 11, 2018).

"We are just beginning to understand the potential applications of cinematic rendering, but we absolutely believe there are important roles for this new technique," first author Dr. Steven Rowe told AuntMinnie.com. "The images are undoubtedly striking, but beyond that, in the near future we and others will begin to apply cinematic rendering to quantifiable parameters and generate meaningful data that we think will demonstrate the utility of the method."

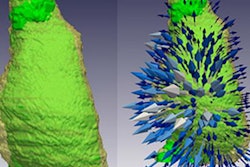

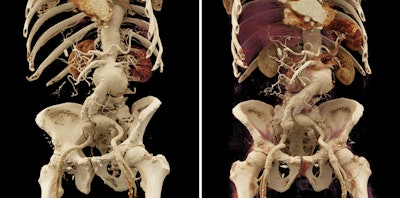

Cinematic-rendered images of a large abdominal aortic aneurysm. Courtesy of Dr. Steven Rowe, PhD.

Cinematic-rendered images of a large abdominal aortic aneurysm. Courtesy of Dr. Steven Rowe, PhD.Clear representation

Though not the most common consequence of blunt trauma, acute aortic injury is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and it poses a serious threat to patient health when it occurs, according to the authors. Treatment of the condition almost always involves an invasive procedure -- usually arteriography or thoracic surgery -- which heightens the need for an accurate diagnosis.

A challenge, however, is that various abnormalities of the aorta mimic an acute aortic injury and often confound its detection, they wrote. Differentiating abnormalities in the aorta from aortic injury "is of paramount importance in order to spare patients the morbidity of unnecessary thoracic surgery."

In the current case, a 23-year-old woman arrived at the emergency department of Johns Hopkins Hospital after a motor vehicle accident left her with pain in her chest and upper back. She had chest wall tenderness and was unable to lie down comfortably for an extended period of time. Her physicians ordered an intravenous, contrast-enhanced CT angiogram of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to evaluate the injury.

The CT angiography scans revealed a nondisplaced sternal fracture, a mediastinal hematoma, and an outpouching near the start of the descending aorta, which is the area most frequently damaged in incidents of traumatic aortic injury. Collectively, these findings suggested a likely acute traumatic injury to the aorta.

Not entirely satisfied with this initial determination, the researchers processed the CT data to create one set of 3D images with volume rendering and another via cinematic rendering software (syngo.via VB20, Siemens Healthineers). It took roughly the same amount of time for them to review each set of images.

"There is undoubtedly a learning curve with both [volume rendering and cinematic rendering], but once appropriate window/level and width presets are available to highlight all of the different tissues and structures of interest, using these methods does not add prohibitively to the time already spent reviewing the 2D images," Rowe said.

Both of these visualization techniques rely on a reconstruction algorithm to generate 3D images from stacked CT scans by sending a projection of light through the volumetric dataset. The principal difference between the methods is that standard volume rendering assumes that a single ray of light passes through the dataset, whereas cinematic rendering uses a global illumination model that takes into account the propagation of thousands of rays of light.

Pronounced advantage

Examining the cinematic-rendered CT scans enabled the researchers to refine their observation of the aorta and make a few key, previously unseen observations:

- The outpouching resembled an incomplete patent ductus arteriosus/ductus diverticulum.

- The outpouching joined the aortic arch at an obtuse angle.

- Bleeding was isolated to the anterior mediastinum, and the fat around the aortic abnormality was normal.

These additional features, along with consultation from the vascular surgery service, helped the team understand that the outpouching was not an acute injury to the aorta, but rather ductus diverticulum -- an outgrowth of the ligament that binds the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta. Follow-up imaging 48 hours after the initial CT exam eventually verified this final diagnosis.

The initial incorrect diagnosis was a result of the folding back of the diverticulum under the aortic arch, which gave the false appearance of an intimal flap in the 2D reconstructed images, according to the authors. A pronounced advantage of cinematic rendering in this particular case was the highly detailed shadowing of the aortic arch onto the ductus diverticulum -- leaving a clear representation of their internal arrangement.

"Although the rate of misdiagnosis of traumatic aortic injuries is actually quite low even without the benefit of cinematic rendering, the consequences of misdiagnosis tend to be significant, either leading to inappropriate lack of treatment for patients with a very serious and life-threatening aortic injury or to needless surgery in patients that have only a ductus diverticulum," Rowe said. "Therefore, we strongly believe any additional images that might help the radiologist (such as cinematic rendering) are crucial."

Ultimate applications

Rowe and colleagues are using cinematic rendering on a daily basis at their institution. Thus far, they have explored its possible clinical applications within cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and oncologic (primary and metastatic tumors) systems.

Several of their experiences include using cinematic-rendered images to detect traumatic injuries and uncover clinically relevant aspects of these injuries (Emerg Radiol, January 2018, Vol. 25, pp. 93-101). They also pointed to the enhanced surface detail of cardiac anatomy, stenoses, and intracardiac neoplasms when using cinematic rendering compared with traditional volume rendering (Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, January-February 2018, Vol. 12:1, pp. 56-59).

"We still have a lot of work to do to figure out the ultimate applications of cinematic rendering," he said. "Potential advantages include better surgical planning (due to the added realism and detail of the images), patient education and engagement (because of the more intuitive nature of the images), and medical student/resident/fellow education."