Researchers from Washington, DC, have successfully used augmented reality (AR) technology to perform image-guided spinal procedures on patients with an accuracy matching that of traditional fluoroscopy, according to research presented at the RSNA 2018 meeting in Chicago.

"This AR technology has the potential to really change the way we perform many [spinal] procedures" presenter Jacob Gibby from the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences told session attendees. "It will help to speed up the process. And where normal, traditional methods can be very cumbersome, like intraoperative MRI, these can be very streamlined and fast ... and reduce overall fluoroscopy radiation exposure to patients."

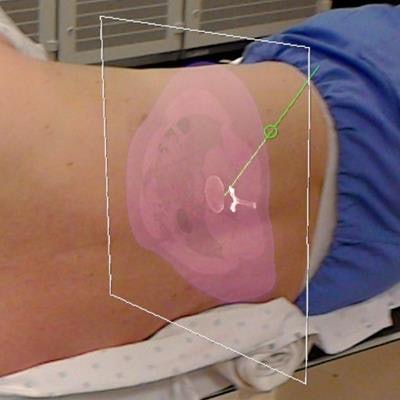

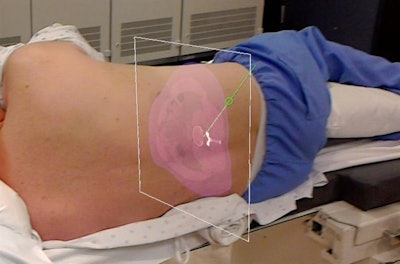

Augmented reality allows clinicians to view MRI and CT scans of the spine, labeled with planned trajectories for needle insertion, directly on a patient. Image courtesy of Jacob Gibby.

Augmented reality allows clinicians to view MRI and CT scans of the spine, labeled with planned trajectories for needle insertion, directly on a patient. Image courtesy of Jacob Gibby.The AR technique involves collecting MRI or CT scans of patients tagged with a QR code localizer along the spine. Clinicians then add the optimal trajectories for needle insertion to these preoperative scans and upload the data into an AR headset (HoloLens, Microsoft) using AR software (OpenSight, NovaRad).

Clinicians wearing the headset can choose to look at the MRI and CT scans or 3D virtual images of the patient anatomy overlaid directly onto the patient. Preoperative imaging with localizers allows for automatic registration of the AR images onto their precise corresponding location on the patient's body. Clinicians can also perform AR functions, such as manipulating the images in space, entirely with hand motions.

To test the viability of intraoperative guidance using AR, Gibby and colleagues simulated four different spinal procedures -- sacroiliac and facet joint injections, percutaneous discectomy, and lumbar puncture -- on radiodense 3D-printed lumbar models based on patient MRI and CT scans. Postoperative contrast-enhanced CT scans confirmed the accurate placement of needles for each simulation (to within at least 2.5 ± 0.4 mm of the planned site).

Following the success of these preclinical tests, the researchers used AR to facilitate the same spinal procedures on actual patients. They first planned the ideal site and positioning for needle insertion by examining 3D virtual models with AR. Next, a neuroradiologist, wearing an AR headset, superimposed the imaging data and the planned trajectory onto the patient's spine to guide the procedure in real-time.

For the facet joint injection, the researchers successfully accessed the appropriate joint space following a trajectory that could not have been established with traditional fluoroscopy due to the presence of bone spurs.

The lumbar puncture case also proved to be challenging because the patient was pregnant. Clinicians failed to extract spinal fluid after multiple attempts with the standard method, but by using the AR technique, a neuroradiologist was able to perform the procedure successfully on the first attempt.

This pilot study demonstrates that AR may be used to guide difficult procedures for which conventional methods of image guidance, such as fluoroscopy, CT, and MRI alone, may not be sufficient, Gibby noted.

"This technology is going to play a significant role in medicine as it begins to roll out," he said. "The question is: Where will radiologists be -- and will they take a central [position] to help move this technology forward?"