Whether it involves physicians, patients, healthcare professionals, or insurance companies, communication is an essential component of day-to-day healthcare practices. Historically, much of that communication has been analog, taking the form of the spoken word as a doctor and patient discuss a care plan. Other examples of analog healthcare communication include a hand-written toxicology report, a printed lab result, and a sheet of x-ray film.

In these formats, the information is relatively easy to protect and control. By storing these physical documents in a secure environment and transferring them by courier, a healthcare provider could readily assure patients their medical information was safe.

However, information stored in this manner is not easily processed for research nor can it be quickly communicated to or shared with a remote peer. Unfortunately, healthcare providers are slow to adopt digital solutions for information generation, storage, or transmission. This reluctance to transition to a digital environment has been noted and identified as "among the most serious threats to the health industry, ahead of rising costs," according to InformationWeek (January 31, 2005, Vol. 1024, pp. 18-19).

In an environment that stores information in digital form, that information may typically be found in two states: either in archive or transmission. Stored digital information is generally considered to be at the least risk as hardware, software, and even physical measures are often taken to ensure the information remains secure and inaccessible to unauthorized users.

Data that is being transmitted is exposed to public systems, and is in jeopardy of being accessed and copied by potentially malicious third-party users. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) document, "Health Insurance Reform: Security Standards: Final Rule" (Federal Register, February 20, 2003, Vol. 68:34) states: "The confidentiality of health information is threatened not only by the risk of improper access to stored information, but also by the risk of interception during electronic transmission of the information."

Required but not supported

This risk must be taken into consideration, as the result of such exposure could have devastating effects on users as well as the patient whose personal information is exposed. John Jones, an attorney at Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis in Philadelphia, indicated in Physician's News Digest (May 2000) that regardless of the status of patient consent, malpractice is sure to arise because of confidentiality breaches during digital communications. He further stated that even though the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986 provides punishment for the illicit capture of any form of digital communication, the sender of an e-mail could potentially still be at risk of civil charges and penalties.

Although legislation for the protection of digital communication in general has existed for a number of years, legislative imperatives for protecting patient information are relatively recent. Even though HIPAA specifies the obligation healthcare providers have for protecting confidential records and their responsibility to log and document medial record activity, the details of how this is to be achieved is left to the responsibility of the implementing facility, according to HHS.

Few healthcare providers possess such expertise in-house or have access to funds required to enlist the consultative assistance of third-party organizations, leaving them with the obligation and constraints of the legislation but little to no useful assistance in meeting those obligations. Because of this, concern over a real solution to confidentiality remains and grows even larger.

The slippery slope of standards

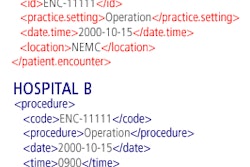

Some consider medical information and communication standards, such as HL7 and DICOM, to be a satisfactory response to the question of security and patient confidentiality. HL7 is widely used in healthcare for the transmission of many types of patient-related information from one system to another. It is used in the transmission of detailed physician visit information, test results, and payment and insurance information. DICOM typically addresses the interoperability of medical imaging devices, such as CT scanners, PACS applications, and other radiology-centric technologies.

The 2002 chair of DICOM Working Group 14, Larry Tarbox, stated that DICOM relies exclusively on the use of secured communications channels. The standard itself does not specify requirements or solutions for ensuring confidentiality; it focuses on interoperability. The result of this is that, although standard adherence may mean that a transmission involving at least two parties may be successful despite the fact two disparate systems are involved, no assurance or even consideration of security and privacy is provided through adherence to the standard.

Because little to no federal funding exists in support of developing standards, those who do adopt a standard such as HL7 do so voluntarily and are unsupported in this process, according to Edward Shortliffe (Health Affairs, September/October 2005, Vol. 24:5, pp. 1222-1223). Subsequently, healthcare providers invest time and money in an attempt to adhere to standards but may find their transmission destination does not. At this point, in addition to having a potential breach in information security through this transmission link, they may not even be able to share applicable medical information with their communication peer.

Home-grown security

Because of the low level of support provided to a facility by legislation and current standards, the quest for a solid solution regarding patient confidentiality and information security leads to the home of digital communication, the information technology (IT) department. It is by basing the digital transmission of patient information on the technology industry-accepted security measures in place and in use that compliance with legislation and protection of patient privacy may be ensured.

In most cases, much of the transmitted medical information is passed between nodes within a hospital network. Because any isolated system is generally considered secure from external intrusion, intranetwork communication is commonly only at risk for internal leaks.

Internal compromise of secure healthcare networks is not a new problem. In 1998, 16 state employees in Maryland sold confidential patient information from the state medical database to an HMO. The betrayal of confidentiality in this manner undermines public trust of healthcare providers and diminishes the perceived value the digital format brings to patients.

In addition to using illegally acquired information for making costly coverage decisions, some companies will go to great lengths to acquire information that may benefit them in many aspects of business. According to an article in Healthcare Financial Management (October 1998, Vol. 52:10, pp. 66-68), 35% percent of Fortune 500 companies stated they have used personal medical information in the hiring-decision process. By considering these examples and understanding the value this information has, and therefore the lengths to which a company will go to acquire it, yet another reason to protect this information is evident.

Internal controls in the form of information security policies are instrumental in protecting sensitive information. In implementing policies, companies are taking reasonable steps to protect themselves from the risks associated with the use of various computer systems.

In addition to policies, facilities may utilize the logging functionality built into many software applications. Software developers may be required to support such functionality to allow their customers to achieve compliance with legislation such as HIPAA. In addition, patient information security and privacy mandates extend to healthcare facilities outside the U.S. Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament demands data security and accountability in the European Union that is quite similar to U.S. legislation.

HIPAA compliance for logging is complex because the rules do not explicitly state the items that must be tracked. They merely state that audit logs must track who accesses protected data stores. Many facilities opt to also include details such as individual user login and logout activity, the required display of patient-specific information, and the modification of patient data.

Considering the software, logging, and policies required to make data as safe as possible within a healthcare facility's network, additional components are required to secure medical information transmitted outside that network. Appropriate hardware and software must be in place and properly configured to maintain the division between external Internet traffic and internal network traffic in a healthcare facility. These items include firewalls, secure socket layer (SSL) servers, and virtual private networks (VPNs).

A firewall is a device installed between the internal network of a facility and the public Internet. It serves the purpose of controlling access to the internal system, and is designed to forward and filter individual messages. An SSL server provides end-to-end security for applications. In a healthcare setting, these applications are often Web servers that publish patient-related data to users outside the facility. As this sensitive information travels out of the hospital network realm, it is protected and kept confidential through the use of this transport layer technology.

VPN technology can serve somewhat the same purpose as SSL in that it serves to encrypt information, protecting it from being viewed by a third party. A VPN solution typically is implemented as a component within the facility that is connected to by users launching a VPN software client. The solution is highly scalable and creates a private network that ensures communication between the client and the host facility remains secure and encrypted.

Considering the lengths to which a healthcare provider must go to achieve and maintain data security for confidential patient information, mistakes may be made in countless ways. Hospital staff members may tape that hard-to-remember passwords under their keyboard or write it on the back of their identification badge. E-mail sent outside the facility is, as a rule, unencrypted and patient information may be included in those messages. In addition, the physical security of hospital-based servers is often overlooked.

Further, legacy systems may have too much trust placed in them -- even though they were implemented years before and have never had their level of data protection reviewed. These legacy systems may present wide-open doors for intruders to access sensitive systems connected to them. A worst-case scenario would be if those legacy systems themselves possessed confidential patient information and it became available outside the facility. Reviewing existing hardware, systems, and configuration is vital and should be performed on a regular basis by IT administrators.

Last off the blocks

For too long, information security has been one of the last items to receive funding from hospital chief financial officers or attention from chief information officers. The lesson that is being learned now is that chronic underfunding of security projects leads to higher costs later. One of the reasons for this is that revenue-generating projects tend to be funded first, leaving the "ancillary" departments of the hospital with the remnants of the budget. However, as security breaches become evident and, more importantly, the repercussions from them, both financial and community reputation costs begin to add up dramatically, according to Healthcare Financial Management (February 2006, Vol. 60:2, pp. 56-60).

Although excellent arguments can be made for funding revenue-generating departments, the departments that are repositories for medical information such as IT, medical records, and radiology have a significantly more prolific role than ever before. The contribution these departments offer a healthcare facility is significant and is relied on by the institution and its external customers, such as referring physicians, clinics, and imaging centers.

All departments in a healthcare enterprise require the capability to communicate information in a secure and confidential manner throughout the confines of its network. Additionally, they must now be able to move information across the Internet to serve remote users or communicate information with third-party enterprises, such as other healthcare providers or insurers. The time is clearly overdue for the medical information industry to focus on security during the transmission of confidential information.

By Rocklyn Lien

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

January 19, 2007

Rocky Lien is a trainer for a medical imaging developer and is responsible for preparing administrators for their role in the implementation and management of PACS. He is a registered technologist with 11 years of experience in the radiology field.

Related Reading

Crafting an RFP for device and systems security, November 9, 2006

GAO: CMS needs to improve IT security, October 4, 2006

Practices that embrace EHR security regulations inspire patient confidence, July 14, 2006

HIPAA compliance remains inconsistent, April 12, 2006

Dealing with HIPAA changes in 2006, April 6, 2006

Copyright © 2007 Rocklyn Lien