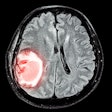

Perhaps for women at high risk who have dense breasts, according to Dr. Wendie Berg, Ph.D., head of the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN 6666) on whole-breast ultrasound screening. The ACRIN 6666 trial, more than half of which is funded by the Avon Foundation (the remainder of its funding is from the National Cancer Institute via ACRIN), consists of 2,809 women; researchers began enrolling participants in April 2004 and ended in February 2006.

Each woman is given a mammography exam and a breast ultrasound exam at entry, then again at 12 months and 24 months. The breast imager that does the ultrasound exam is blinded to the mammography exam, Berg said. The first results are expected this fall.

"The main issue is whether the combination of screening ultrasound and mammography is better than mammography alone for this population," Berg said. "We already know that ultrasound is not going to replace mammography, but it's important to give it a fair and objective evaluation."

Other studies have been conducted to evaluate breast ultrasound, and their results were promising: Breast ultrasound found three to four more cancers per 1,000 women not found in mammography. But these previous studies had a few limitations, according to Berg:

- They centered on average-risk, rather than high-risk, women.

- The breast imagers that performed the ultrasound exam were aware of the results from the woman's mammogram, which opens up the potential for bias.

- They didn't evaluate and/or report results for the women in subsequent years.

One of the exciting characteristics about breast ultrasound is that it not only appears to find cancers mammography misses, but 86% of the cancers it finds are node-negative, Berg said. "For breast cancer screening tests to be effective, they have to find the cancers that haven't yet spread," she said. "It's fair to say that if ultrasound can find these cancers, using it should save lives."

-- Kate Madden Yee