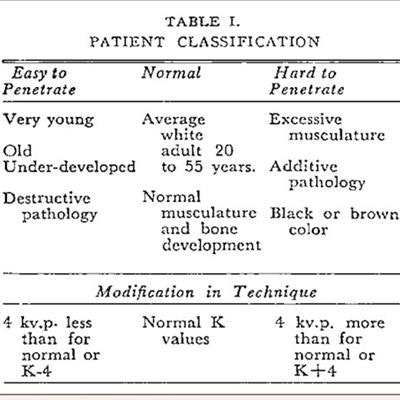

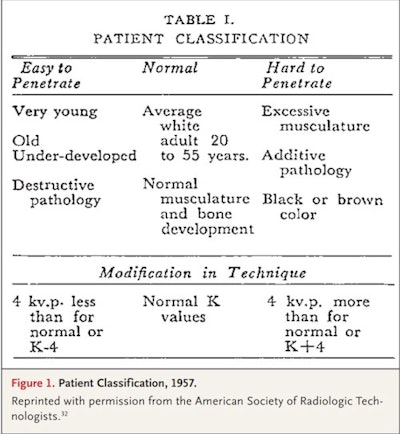

Black people historically received higher x-ray radiation doses due to mistaken racial beliefs about their body habitus and skin color, and it was common practice as late as 1968 to set higher radiation dose levels for Black patients, authors wrote in a September 7 article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a practice the authors called "race adjustment," guidelines used in the first half of the 20th century for performing x-ray exams on Black patients routinely recommended using higher kVp settings than for other individuals due to the false belief that it was more difficult for x-rays to penetrate the tissues of Black patients. For example, a 1905 review article falsely claimed that darker skin offered more resistance to x-rays.

This belief -- that Black people have denser bones or thicker skin -- permeated medical textbooks and clinical practice recommendations throughout most of the 20th century. This led radiologists to increase radiation dose levels for a single x-ray by up to 60% in Black patients.

X-ray classification card from 1957 indicating recommended radiation doses for different types of patients. Image courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine.

X-ray classification card from 1957 indicating recommended radiation doses for different types of patients. Image courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine.The practice prevailed until 1968 when it was discontinued, largely due to the impact of an exposé by consumer advocate Ralph Nader, the authors wrote. And even then, the change was resisted by professional societies like the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the American Dental Association (ADA), wrote science historians Itai Bavli, PhD, and Dr. David Jones, PhD, of Harvard University in Cambridge, MA.

Analysis of how and why this particular institutionalization happened in the 1960s can provide insights applicable to the reckoning and reassessments of healthcare disparities that are occurring today, they added.

The practice of giving larger x-ray doses to Black patients was brought to national attention when the U.S. Senate held hearings on the Radiation Control for Health and Safety Act of 1968. The legislation was prompted by growing concern about the safety of radiation equipment and the laxity of existing regulations.

At the hearings, Nader testified that technologists were exposing Black patients to higher x-ray doses than white patients because of a "generalized intuition or folklore."

This claim led to larger debate among Nader, senators, and health officials, and prompted objections and denials from the ACR and the ADA, according to Bavli and Jones. They quoted William Stronach, executive director of the ACR, who wrote in a letter dated May 29, 1968, that Nader's allegation was "a combination of misunderstanding and half-truths which needs untangling."

Nader shot back that the ACR was only seeking to protect its autonomy to define professional standards, a desire that led the group to deny a practice that radiologists simply could have acknowledged and reassessed, the authors wrote.

Ultimately, Nader's testimony prompted the Senate to request more information, with the U.S. National Center for Radiological Health issuing a formal statement on June 18 advising against using race to adjust x-ray exposure for diagnostic imaging.

"One might have expected x-ray technologies, which see through the skin to deeper structures beneath, to be spared racialization. They were not," Bavli and Jones wrote.

To its credit, the ACR was one of the first medical societies to address racial injustice after George Floyd's murder in May 2020, the authors noted.

Ultimately, the percentage of x-rays taken of Black Americans that used increased exposures is unknown, as is how many people were potentially harmed, the authors wrote.

Lessons to be learned include that superficial social and medical beliefs can become embedded in medical practices and institutions. The race adjustments for x-rays were introduced even though no compelling evidence had been published to justify them. In fact, race adjustment is still used uncritically with Black patients in many areas of U.S. medicine, the authors wrote.

Second, the easy racialization of x-rays highlights the peril of widespread use of race categories, the authors suggest. Even when a specific use of racial categories and race adjustment might benefit patients, physicians should consider the lessons of history and proceed with caution, interrogating the evidence, the possible biases that influence decisions about diagnosis and treatment, and the possible harmful effects, they wrote.

"The history of radiology provides another example of how the institutionalization of race categories -- the translation of beliefs about race into formal recommendations, policies, and practices -- can perpetuate health inequities and harm marginalized groups," Bavli and Jones concluded.