Is there a role for deception -- most commonly, hiding the true purpose of a project -- in medical research? It depends, according to an article published June 22 in Academic Radiology in which researchers reviewed their experience with a 2017 radiology residency bias study that used the method.

Concealing an experiment's purpose in order to "avoid conscious reactivity in participants that might otherwise compromise the data, or to gain participation that might otherwise have been declined" is the most common form of research deception, wrote a team led by Dr. Charles Maxfield of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC.

"Deception is a common feature of research design, although not commonly employed in the medical literature," the authors noted. "When the value of the findings are socially important and cannot be obtained by methodological alternatives, and if the possibility of harm to participants is minimal, research using deception can advance scientific knowledge and promote the general good of society."

The first rule of research that involves humans is that the subject's autonomy is respected, primarily by being informed about the nature of the research, Maxfield's team noted. But sometimes "honestly informing subjects of the purpose for a study can present an obstacle to answering important research questions when full disclosure may influence the very phenomena under investigation," the group wrote.

"In these cases, deception of research subjects may be experimentally necessary in order to capture ecologically valid behavior outcomes," the authors wrote.

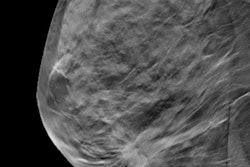

How might this play out in radiology? Maxfield and colleagues described an experiment they conducted in 2017 to study discrimination against obese or "unattractive" radiology residency candidates. They created fictitious radiology residency applications that included academic and nonacademic accomplishments as well as a picture of the supposed candidate across a "spectrum of facial attractiveness and obesity." Radiology faculty at five academic centers believed they were screening actual applications as part of their department's residency selection process.

The study found that obese and less attractive applicants did in fact receive lower scores and were less likely to be invited for an interview.

"Without using deception, it would have been impossible to make these findings," Maxfield's group wrote.

But the study came with a cost. When informed of the deception, most participants understood that it was necessary to use the fictitious applications for the study. Yet some felt betrayed and opted out of follow-up research. In fact, a formal complaint was filed with the Investigational Review Board (IRB) by one participant; although the IRB confirmed that the study was above board, the research team granted this participant's request that their data be withdrawn.

"We remain concerned that participants will be less inclined in the future to participate in the resident selection process or in departmental research," the team wrote.

Deception as a research tool requires careful consideration, according to the authors.

"A careful balance between methodological and ethical considerations must be sought by those considering this methodology," they concluded.