VIENNA - What do expert radiologists know that less experienced radiologists don't? How to search through images and what to look for, Irish researchers reported during a presentation on Saturday at ECR 2014.

After performing an observer study with eye tracking on four groups of readers, a team led by Dr. Brendan Kelly of the University College Dublin (UCD) School of Medicine and Medical Science also concluded that radiologists first learn how to search like an expert before they diagnose like one.

"It's not just what you see, it's the way you see it that counts," he said.

Dr. Brendan Kelly from UCD School of Medicine and Medical Science.

Dr. Brendan Kelly from UCD School of Medicine and Medical Science.

The researchers sought to determine how image interpretation skill develops throughout a medical career, as well as to provide an evidence base for training. Research in the literature has shown that expert radiologists tend to fixate on pathology very quickly and don't need to dwell very long to make a decision. These visual search tasks are a learned skill, Kelly said.

Of course, it's crucial to make the correct decision once an abnormality has been perceived, he added.

"It's all very well to move your eye to that fine lung nodule that could be indicative of that pathology," he said. "But if you don't make the correct decision on what you see, there wasn't much point to looking at it in the first place."

The researchers formed four clinician groups to participate in the research project, including five consultant radiologists (who served as the reference expert group for the study), four radiology registrars (fellows), five senior house officers (SHOs), and six interns.

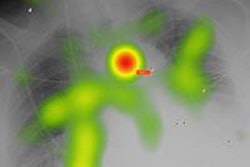

These participants were asked to read 30 chest radiographs, of which 14 had a pneumothorax, and they recorded their level of confidence in the presence or absence of a pneumothorax. While they were interpreting the studies, their eye movements were tracked by a Tobii TX300 eye tracker. Receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analysis was performed to determine diagnostic accuracy.

The sessions yielded data that included more than 15,000 unique observations and 750 diagnostic decisions. The group analyzed factors such as time to first fixation (how long it took to see the pathology), fixations before localization, fixation duration (dwell time), and total visit count (how many times they returned to an area they'd already seen, an indication of indecision).

| Eye-tracking results in 4 readers groups | |||||

| Group | Average time to first fixation | Average total fixation duration | Average max visit count | Fixations before localization | Average time taken |

| Consultants | 0.649 sec | 0.34 sec | 1 | 2.333 | 323.6 sec |

| Registrars (fellows) | 0.648 sec | 0.5117 sec | 1.111 | 1.679 | 313 sec |

| SHOs | 1.912 sec | 0.674 sec | 1.833 | 4.038 | 574 sec |

| Interns | 2.153 sec | 1.337 sec | 2.067 | 4.738 | 973.4 sec |

All of the eye-tracking metrics improved significantly between the registrar and SHO level (p < 0.001), but there were no significant differences between the intern and SHO groups or between the registrar and consultant level.

The point of statistically significant improvement differed for diagnostic accuracy. ROC analysis showed that accuracy improved significantly only from the registrar to the consultant level (p = 0.009)

This shows that an expert search pattern predates the development of expert levels of diagnostic accuracy, Kelly said.

"You learn to see like an expert quicker than you learn to make decisions like one," he said.

Specific training is therefore required to improve radiology expertise. "At the novice level, it's the search pattern where you need to intervene, whereas at the expert level it's the decision-making," Kelly said.