Can 3D mammography be the next large-scale population screening tool? The quest for cost-effective individual screening methods remains a priority for breast cancer imaging specialists, but the complexity of different factors in screening presents a huge challenge to researchers. Results from several trials in Europe may spell change for screening programs.

While individual screening is most likely be the optimal weapon to wield in the fight against breast cancer, the evidence to support large-scale implementation remains scarce, and limited health budgets also hamper such programs. The compromise of "a middle way," using evidence-based 2D mammography screening that has proved a cost-effective method for most women, would seem a practicable tool. But 3D mammography (digital breast tomosynthesis [DBT]), which is considered to have clear advantages for detecting cancer in dense breasts, is now emerging as a potentially viable population screening method.

It could take five to 10 years for a transition from 2D to DBT in the general population, if reliable data support a change, according to Dr. Sophia Zackrisson.

It could take five to 10 years for a transition from 2D to DBT in the general population, if reliable data support a change, according to Dr. Sophia Zackrisson."For the moment we must stick to evidence-based screening methods for women at moderately increased risk of breast cancer, and at the same time, build on existing data for other methods to prove that there could be another more cost-effective protocol," said Dr. Sophia Zackrisson, senior consultant radiologist and associate professor of radiology at Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden. "Three large prospective trials in 3D mammography have taken place in Norway, Sweden, and Italy and are yielding some initial promising results."

During their design, it was believed that the trials would show that 3D mammography would prove most beneficial for screening women with dense breast tissue, explained Zackrisson, who is presenting at today's "ECR meets Nordic countries" session. However the first results are now in from all three trials, and, startlingly, additional cancers have been found with 3D mammography in all types of breast, with no clear trend for dense breasts categorized as BI-RADS 3 and BI-RADS 4, she said.

Other screening methods, such as handheld or 3D automated ultrasound and also contrast-enhanced MRI, are not suitable to roll out in large-scale screening programs, but remain tools for individual screening of high-risk women. In handheld ultrasound, a recent U.S. report of a large modeling trial found no cost benefit when comparing the yield of extra cancers detected versus the high number of false-positive findings. Meanwhile, MRI is already used as an individual screening tool in high-risk women who are BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive.

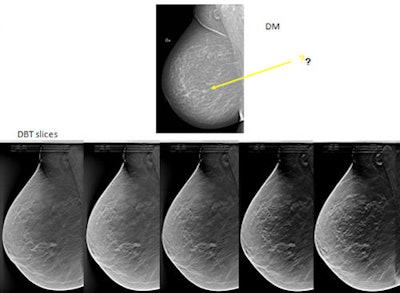

Tumor not easily seen on 2D digital mammography. With 3D DBT, it is obvious there is a spiculated tumor. This shows five tomosynthesis slices in which the lesion is in focus. The breast is not especially dense, but a small amount of overlapping tissue is enough to hide the tumor on digital mammography. Images courtesy of by Dr. Sophia Zackrisson, Skåne University Hospital, Malmö.

Tumor not easily seen on 2D digital mammography. With 3D DBT, it is obvious there is a spiculated tumor. This shows five tomosynthesis slices in which the lesion is in focus. The breast is not especially dense, but a small amount of overlapping tissue is enough to hide the tumor on digital mammography. Images courtesy of by Dr. Sophia Zackrisson, Skåne University Hospital, Malmö."The problem is that we have an established screening strategy for low and average risk in the fatty breast and for women at high risk and very high risk. However, for women with dense breasts, some of whom will be at a higher risk than those with fatty breasts, there is no such screening strategy," said Zackrisson, who is also section head of oncologic imaging.

DBT may provide an alternative to 2D mammography, given that it seems to already be detecting additional cancers in all breast types. However, the question of changing screening methods for the general population is a complex issue that needs long-term trials to ascertain certainty of improved results. Such long-term trials will establish cost-effectiveness in terms of false-positive rates, human resources required, reading time, and overdiagnosis of indolent slow-growing cancers that wouldn't have caused harm or death during the individual's life time.

While none of the DBT trials were designed or powered to measure overdiagnosis, interval cancer rates can be used as a surrogate measure of whether new screening methods are picking up an increased number of relevant cancers.

"Because already we have to screen a lot of healthy women to find cancer, any new methods shouldn't introduce a too high number of false positives or more overdiagnosis into results. If we get good trustworthy data, we might see some changes in five to 10 years, but it will take a long time for a transition from 2D to DBT in the general population, if at all," she noted, adding that if no decreased interval cancer rate could be perceived, then the evidence would not support a change.

Zackrisson also pointed to the need for risk estimation models as part of the strategy to catch women who might slip through the current and any future screening net. These models would help to assess each woman's individual risk, and the Gail model and the Tyrer-Cuzick model are two examples to help assess individual risk. These two models are not yet accurate enough to be used in clinical practice, but the idea is that the preimaging data provided by a tried and trusted risk estimation model would take into account not just breast density, but also age, reproduction and hormonal influences, family history, and breast disease problems such as cysts, benign precancerous stages, and cellular pattern change.

A good risk prediction model would provide a number for individual risk, and this would help screening program organizers decide the cut-off point for moderate, high, and very high risk.

There should be a frank, objective, and open discussion about the pros and cons of any screening program, according to Zackrisson, both to find the optimal method and provide the latest information, so that women can make up their own minds as to whether they wish to participate.

"The bigger question is: Are we using the money in the right way? With limited budgets we need to ask whether instead of funding breast cancer screening we should not instead be helping people to quit smoking," she noted. "I'm always open to debate on the topic. This is a complex issue. Individual screening sounds easy but it's not. One should always think twice before implementing such programs."

ECR delegates will also learn about mammography screening in Denmark, which has a high incidence of breast cancer and high age-standardized breast cancer mortality. Mammography screening in Denmark has been intensively discussed for over two decades. While the Danish Parliament decided in 1999 that Danish women aged 50 to 69 should be offered mammography screening every second year, national mammography screening was not implemented until 2007.

Dr. Ilse Vejborg believes the Danish trial proves beyond doubt that mammography screening has an impact on breast cancer mortality, but urges researchers to remain aware of the balance between benefits and harms.

Dr. Ilse Vejborg believes the Danish trial proves beyond doubt that mammography screening has an impact on breast cancer mortality, but urges researchers to remain aware of the balance between benefits and harms."At the same time we have two longstanding programs which combined have covered around 20% of the target population of women aged 50 to 69 years in Denmark. As we -- in contrast to, for instance, Norway -- have had a very low percentage of opportunistic screening we have had a "natural experiment," which has given us a unique opportunity to perform research on a screened population of women compared to unscreened," said Dr. Ilse Vejborg, head of radiology at the University Hospital of Copenhagen Rigshospitalet and head of the Regional Mammography Screening Programme.

After 10 years of mammography screening in the Copenhagen municipality, breast cancer mortality was cut by 25% in the whole target group of invited women and by 37% among those who participated one or more times. Before screening started, women in Copenhagen had significantly higher breast cancer mortality than the rest of the country. After 10 years of screening, breast cancer mortality in Copenhagen was significantly lower than in the rest of Denmark, she added.

Combined statistics from the two longstanding programs in Copenhagen municipality (started 1991) and Funen County (started 1993) show that overdiagnosis among participants is between 1% and 5%.

"Mammography screening without doubt has an impact on breast cancer mortality, but it is important to be aware of the balance between benefits and harms. To minimize the harms and optimize the benefits, the screening program must have a high-quality standard which should be monitored continuously," Vejborg said, pointing to 11 indicators used to monitor the quality of the Danish program.

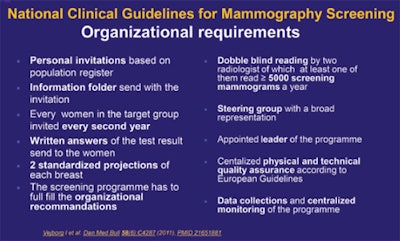

Such high-quality screening programs work in accordance with European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Mammography Screening and Diagnosis, she noted. The criteria include the following: The program should provide personal invitations based on population registers; each woman who does not decline should be invited every second year or in accordance with the defined interval in the program; double-blind readings should be undertaken by two radiologists, at least one of whom should be a high-volume reader of more than 5,000 mammograms a year; and performance and early surrogate indicators -- e.g., participation rate, recall rate, technical recall rate, operation ratio for benign versus malignant lesions, percentage of small cancers 1cm or smaller, and percentage of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) should be monitored and be in line with the recommendations.

High-quality programs must adhere to guidelines and be continuously monitored with indicators that remain in line with recommendations, according to Dr. Ilse Vejborg.

High-quality programs must adhere to guidelines and be continuously monitored with indicators that remain in line with recommendations, according to Dr. Ilse Vejborg.The five regions involved in the Danish trial are required to send data to the National Mammography Screening database.

"We now have data from three biannual screening rounds showing that the Danish mammography screening program is working to a high-quality standard," she concluded.

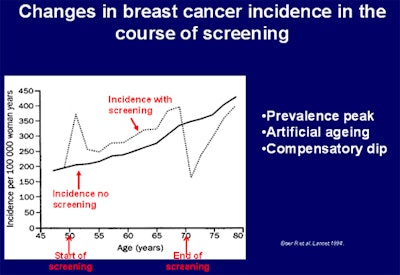

Overall, invited women participating in the Copenhagen program experienced a drop in breast cancer mortality of 25%. Image courtesy of Dr. Ilse Vejborg, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen.

Overall, invited women participating in the Copenhagen program experienced a drop in breast cancer mortality of 25%. Image courtesy of Dr. Ilse Vejborg, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen.Originally published in ECR Today on 4 March 2016.

Copyright © 2016 European Society of Radiology