The public desire for lung cancer screening and the ability of the medical profession to implement it are currently at odds, despite recent findings that suggest screening via low-dose CT can reduce mortality. The problem is lung cancer screening remains controversial and is not as straightforward as most people think, according to Dr. Stefan Diederich, PhD, head of diagnostic and interventional radiology at Marien Hospital, Dusseldorf, Germany, and president of the International Cancer Imaging Society.

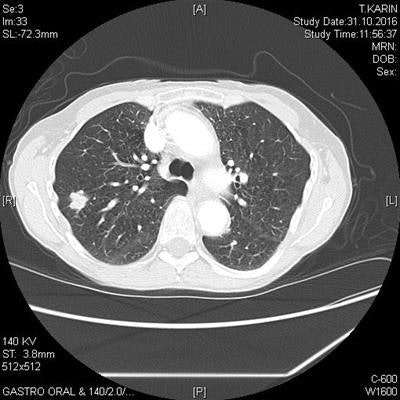

Advances have been made, but until recently, trials that looked at the effectiveness of detecting lung cancer via screening and the ability to save lives have returned disappointing results and no recommendations for use. The sea-change in attitude, however, first began with studies using a low-dose CT scan for the identification of malignant nodules. This led to an unexpectedly high number of cases of lung cancer discovered at early stages, Diederich said.

The randomized National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was conducted to see if CT could save lives, and the study reported a high number of lung cancer cases discovered at early stages, associated with a 20% reduction in mortality from lung cancer via screening. This was the first time such evidence had been found, and it highlights the significance of early detection, he added.

As a result, several recommendations were made to implement CT screening programs, as long as the criteria met those used in the NLST, but only a handful of countries, including the U.S., have actually implemented any form of screening program, and there is no movement to introduce an EU-wide scheme.

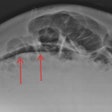

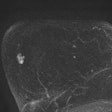

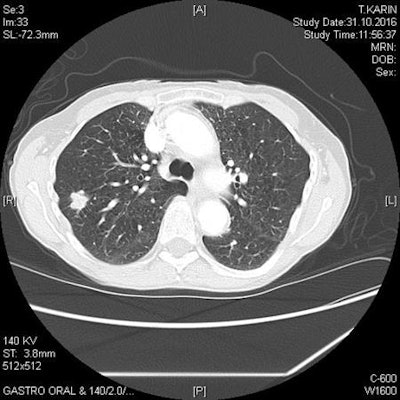

Solid lobulated nodule in the right upper lobe represents non-small cell lung cancer in a 73-year-old female smoker. Image courtesy of Dr. Stefan Diederich, PhD.

Solid lobulated nodule in the right upper lobe represents non-small cell lung cancer in a 73-year-old female smoker. Image courtesy of Dr. Stefan Diederich, PhD.While the public's wish for a screening program might be there, Diederich said a number of issues were hindering any widespread implementation. For instance, the NLST generated almost more questions than it answered -- for instance, will risk profiles different to those in the NLST benefit from screening, and how long and frequent should the screening regime be?

In addition, there were concerns that screening was still not effective enough. Lung cancer is the lead cancer killer worldwide because symptoms don't present until the cancer is at an advanced stage, by which time the survival rate is low; just 15% of people diagnosed with lung cancer will live for five years.

"So, 85 out of 100 people with lung cancer will die in the next five years. But even with this new screening, 68 individuals out of 100 will still die. That's two in three people dying even with screening," he explained. "It is a step in the right direction and why most medical societies recommend screening with CT. But mortality is only reduced; screening doesn't eliminate it."

There are two other issues: first, the exposure to radiation from the CT scans, which, in itself, can lead to cancer, and second, the anxiety that patients may feel while waiting for confirmation on whether identified nodules are benign or malignant. The bigger problem, however, is cost and who pays, according to Diederich. Screening means follow-up scans and the likelihood of regular annual screening, all at a cost to already struggling healthcare systems. Meanwhile, the modern drugs to treat lung cancer are increasingly expensive compared with treatments in the 1990s -- so "now people die with a higher cost," he commented.

Furthermore, the smokers who fall into the high-risk group for lung cancer are also at risk of numerous other diseases, such as other cancers and cardiovascular disease.

"As a result, if you cure a patient through screening, the problem is there might be additional costs to the healthcare system in the future," he continued. "Screening might be beneficial to the individual, but for society it might cost more if screening is implemented. The cost-effectiveness of screening is a complicated issue."

As such, predicting what the future might hold for lung cancer screening is difficult. In today's session, Dr. Anand Devaraj, a consultant thoracic radiologist at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust, U.K., and honorary senior lecturer at the Imperial College London National Heart and Lung Institute, intends to talk about the opportunities for further research in lung cancer screening and discuss these unanswered questions around cost-effectiveness and implementation.

He told ECR Today that there were opportunities to focus efforts on understanding how screening programs can be optimized in the future and that focus needed to concentrate on some key areas. These included selecting the most appropriate people for screening, and sufficiently engaging with them to ensure they turn up for their screen; identifying workforce requirements to implement screening; understanding the optimal frequency of screening; and how to best manage findings from scans, both lung nodules and other incidental findings as well.

"Some of the answers to the questions will be provided from analyses of data from existing screening trials," Devaraj said. "For other aspects, new research studies will be needed, either randomizing screening patients to different interventions or by modeling and simply comparing outcomes with historical data."

One trial in progress at the moment is the Dutch-Belgium NELSON trial, which many health authorities in Europe are waiting on, he said. "A second positive trial would be immensely supportive of lung cancer screening, and its results will also go some way to answering questions related to cost-effectiveness and applicability in different populations."

There is certainly a growing appetite among the medical community and patients for lung cancer screening, especially as early diagnosis is key to preventing lung cancer deaths. But while there are no guidelines currently, any future implementation will be a challenge and is likely to have a significant impact on many aspects of radiology, he added.

Originally published in ECR Today on 2 March 2017.

Copyright © 2017 European Society of Radiology