Gadolinium-enhanced MRI scans have been the gold standard in suspected cases of benign tumor vestibular schwannoma and multiple sclerosis, but given the growing evidence that the contrast agent can leave deposits in the brain, debate has ensued about how to image wisely.

Gadolinium has already been a subject of debate with questions about its cost-effectiveness, but the news that gadolinium has been found deposited in the brain and in other body tissues -- even though there is no evidence to suggest it causes any adverse effects -- has increased the intensity of the discussions. The question many radiologists have been asking is: Is it always necessary to use gadolinium contrast agents in imaging? In regard to vestibular schwannoma and MS, this question will be explored at today's Pros and Cons Session.

"The use of contrast-enhanced MRI, during observation of a known vestibular schwannoma or surveillance after surgical or radiotherapy treatment, has become questioned," said Dr. Francesca Pizzini, a neuroradiologist at University Hospital Verona in Italy.

The problem has arisen because MRI has a central role in evaluating vestibular schwannoma in first diagnosis and follow-up, with contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images considered to be the gold standard for tumor assessment.

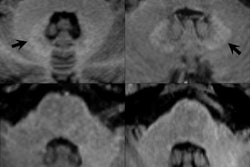

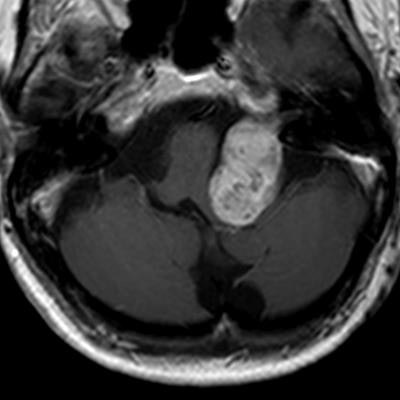

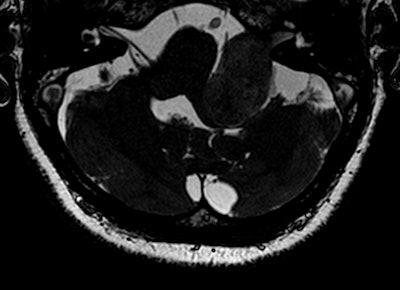

High-resolution T2-weighted (above) and enhanced T1-weighted (below) images of large intra- and extrameatal vestibular schwannoma. All images courtesy of Dr. Francesca Pizzini.

High-resolution T2-weighted (above) and enhanced T1-weighted (below) images of large intra- and extrameatal vestibular schwannoma. All images courtesy of Dr. Francesca Pizzini."Gadolinium-based contrast agents increase the relaxation rate of water protons in the region where they distribute, thus providing relevant information on pathologies, involving changes in the vascular density and permeability and structural differences," she said. "Unenhanced sequences available are not currently providing comparable and alternative structural details."

Her hope is that today's session will also assess the diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution T2-weighted scans as an alternative to gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted scans in different clinical settings.

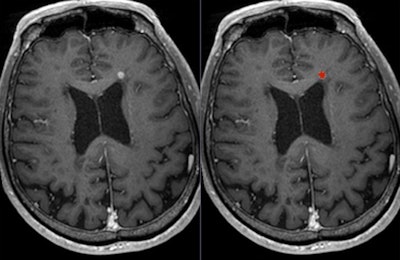

Postgadolinium T1-weighted image shows lesion (left: original image; right: lesion marked in red).

Postgadolinium T1-weighted image shows lesion (left: original image; right: lesion marked in red).Most of the controversies regarding the use of gadolinium focus on the primary diagnosis -- rather than follow-up and post-treatment -- of vestibular schwannoma, which is a benign intracranial tumor of the myelin-forming cells of the vestibulocochlear nerve in the internal auditory canal next to the brain. Patients may present with sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and balance problems, but only a small percentage of people with these symptoms will have vestibular schwannoma, explained Dr. Berit Verbist, a neuro and head and neck radiologist at Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

Thus, this is one of the arguments given as to why there is no need to use gadolinium in diagnosis, both from a cost and safety perspective.

"Several studies propagate screening by noncontrast enhanced MRI. Yet, by definition, screening means testing of an asymptomatic population to identify those who are susceptible to a given disease," she said, adding that she plans to draw on the scientific literature in today's presentation to help inform radiologists' decision-making and enable them to image wisely.

Verbist suggested instead that clinicians should "prescreen" patients, selecting only those with symptoms, at risk of vestibular schwannoma, to have an MRI with gadolinium. "That way you only image selected patients," she said, noting that the sensitivity of gadolinium for picking up very small lesions means any disease can be identified in the early stages in these high-risk individuals. While efforts are being made to define criteria of patient selection for imaging, it is important to bear in mind there are presently no reliable nonimaging tests to identify high-risk individuals, she continued.

"If you decide not to use gadolinium, then you have to enhance awareness of clinicians and counsel the patient that small schwannomas and other diseases may be missed," Verbist said.

Dr. Wim Van Hecke, chief executive of Belgium-based start-up firm icometrix who will be speaking today about imaging of MS, agreed that given the recent discussions about gadolinium and its role in disease diagnosis and follow-up, it was important to evaluate its use and clinical necessity. He thinks follow-up MRI scans in MS using contrast should be questioned.

"I believe that for the diagnosis of MS, the use of a gadolinium-enhancing scan is still highly recommended. ... For the follow-up MRI scans, it should be a clinically informed decision, involving the treating clinician and the patient," he noted. "We indeed observe that the use of gadolinium for the follow-up scans is becoming less and less the rule. Instead, a gadolinium scan is requested in specific cases when its use can potentially answer a clinical question."

While, the use of contrast-enhanced MRI scans is the only way to observe blood-brain-barrier disruption due to an inflammatory lesion, Van Hecke said that recent developments of imaging analysis techniques allowed radiologists to evaluate and quantify new and enlarging T2/fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) lesions, which also represent disease activity in patients with MS.

As awareness of gadolinium retention grows, he thinks it is important to communicate clearly with neurologists, clinicians, and patients, on the use of the contrast agents. Ultimately, more research is needed to evaluate gadolinium retention in the brain, he added.

Pizzini agrees that more clinical studies are required. "There is a need for wise use of the available gadolinium-based contrast agents and/or of alternative unenhanced sequences until any possible health risks will be completely excluded and until new kinetic/thermodynamic stable gadolinium complexes will be discovered."

In many cases, wise imaging will come down to a case-by-case basis, and it is important now to take more clinical information into account before setting an imaging protocol for patients, she said.

Originally published in ECR Today on 2 March 2018.

Copyright © 2018 European Society of Radiology