Time is of the essence when it comes to a polytrauma patient, yet numerous questions continue to arise about how and who should be scanned and for which conditions. For a close-knit multidisciplinary trauma team, making the right imaging decisions for patients with severe injuries can be complex and a matter of life and death. Trauma specialists will share their experiences at today's session.

Advances in radiology have played an important role in the management of polytrauma patients -- those with multiple and potentially lethal injuries, such as a combination of a pelvic ring fracture with laceration of the bladder or a hemothorax with blunt aortic injury. But specific guidelines on imaging such patients are in short supply, creating a multitude of questions, said Dr. Monique Brink, radiologist at Radboud University Medical Centre in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

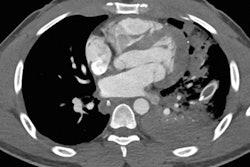

Volume-rendered, thick slab reconstruction of a thoracoabdominal trauma CT scan of a polytrauma patient with, among other injuries, a right-sided diaphragmatic rupture with herniation of the liver and the gallbladder into the thoracic cavity and also dissection of the left renal artery. Image courtesy of Dr. Monique Brink.

Volume-rendered, thick slab reconstruction of a thoracoabdominal trauma CT scan of a polytrauma patient with, among other injuries, a right-sided diaphragmatic rupture with herniation of the liver and the gallbladder into the thoracic cavity and also dissection of the left renal artery. Image courtesy of Dr. Monique Brink.Polytrauma patients generally undergo primary care according to advanced trauma life support (ATLS), a training program for the management of acute trauma cases that provides a solid framework and common language based on treating what kills people first. Prior to this, however, the radiologist has already been involved in the preparatory time-out procedure and briefing on the incoming polytrauma patient. This can provide the information needed for the radiologist to decide when and how to perform imaging, determine which examinations are justified and which modalities should not be used, and work out how the CT protocol should be tailored, she explained.

"The radiologist should take the lead in deciding how that imaging should be tailored to the specific trauma patient, and the radiologist should quickly and appropriately communicate on the most life-threatening imaging diagnoses first," noted Brink, adding that the radiologist should also advise whether further imaging if necessary.

This represents a major challenge, especially when specific guidelines on how and who should be scanned are only partly available. For example, no general consensus criteria exist for the justification and scanning protocol of whole-body trauma CT, although some decision tools have been developed to guide the use of brain, chest and neck CT, and a few good quality prospective studies on this topic have been conducted, she continued. Furthermore, there are significant and specific questions around which patients should undergo CT angiography of the neck to exclude blunt carotid injury and whether radiologists should perform split bolus CT in all patients.

Brink plans to address some of these issues today, and she intends to update ECR delegates on the most relevant guidelines on trauma imaging, while other speakers from the multidisciplinary trauma team will outline how to understand which traumatic diagnoses are game changers.

She acknowledged there was an issue around who should supervise or perform trauma imaging evaluation, noting that the diagnostic approach of a trauma CT scan is different to any other total body CT scan, for instance.

"Should this be a dedicated emergency radiologist with both general knowledge of all body parts, and specific competencies in acute radiology? Or should every radiologist invest in trauma radiology experience and knowledge?" Brink asked. "Are senior residents on-call competent enough to perform trauma radiology without immediate supervision by a radiologist? Is 'scan slicing' (primary evaluation of different body regions by different radiological subspecialists) a good idea or does this interfere with adequate teamwork?"

Members of the multidisciplinary trauma team assess a patient. Image courtesy of Dr. Joost Peters. Copyright: Frank Muller/Zorg in Beeld.

Members of the multidisciplinary trauma team assess a patient. Image courtesy of Dr. Joost Peters. Copyright: Frank Muller/Zorg in Beeld.Indeed, there was a further question about whether radiologists should position themselves in the trauma bay.

"You could argue that the presence of a (resident) radiologist during the whole resuscitation process is not efficient, and hard to implement in daily practice. This can be compensated by placing radiological workstations next to the emergency rooms and the CT scanner -- but this still remains a hospital-wide discussion on priorities," Brink said. "We believe that the direct benefit of the presence of radiology in the trauma bay highly outweighs the cost in a level 1 trauma center. ... The survival of trauma patients improves if the trauma team collaborates closely and systematically."

Dr. Joost Peters, a consultant in trauma surgery at the Radboud University Medical Centre and one of today's multidisciplinary speakers, noted that radiologists were an essential link and valued team member when it came to polytrauma patients and emphasized the need for communication.

From a trauma surgeon's point of view, "it is essential that we communicate regarding time management and findings from scans," he said, emphasizing that radiologists needed to be aware of the survey phase, speak the "common language" of ATLS, and realize that time is of the essence. "To obtain optimal communication and consequently good results, the fundamental guidelines of ATLS must be familiar to all involved in primary trauma care in the emergency department, including the radiologist."

Peters also noted, perhaps controversially, that sometimes it is not possible to wait for scan findings because the nature of the life-threatening injuries may not allow for any delays. "It is sometimes difficult to decide if you have the time to obtain radiological information," he said. "Sometimes the only right place (for the patient) to be is in the operating room."

However, he believed that in the future, scanning would be faster and more detailed, greatly helping the trauma team when dealing with a patient and providing answers to many of the current questions. Furthermore, he also believed hybrid operating rooms with more synchronized interventions would become more common. Likewise, Brink spoke of improved scanning guidelines and patient selection, as well as rapid computer-aided or even automated diagnosis of injuries in the future.

Originally published in ECR Today on 4 March 2018.

Copyright © 2018 European Society of Radiology