Keep aware of the need to protect imaging equipment from cyberrisks that pose a threat to the safety of patients and institutions, urged Dr. Jacob Sosna, president of the Israeli Radiology Association. There is a terrifying possibility that a cyberattacker could alter the radiation dose given to a patient during a CT scan, and an attack on the hospital's air-conditioning may shut down and damage CT and MRI machines that function within a narrow temperature range, he warned ahead of today's session on cybersecurity.

"At home, everything is computerized, and we need to be aware that our work environment is the same," he said. "We are all connected to the web and threatened by cyberattacks."

In a slightly less alarming scenario, a ransomware attack might block access to patient data unless a bitcoin ransom is paid. He plans to give examples during his talk, including the WannaCry ransomware attack that hit the U.K.'s National Health Service (NHS) in May 2017.

Sosna, who is chairman of the radiology department at Hadassah Medical Centre in Jerusalem, recommends asking vendors about cybersecurity when procuring new equipment. Radiologists also should be aware of the security risks posed by patients and staff bringing in external data, such as MR images on a USB stick or a CD, which could be infected with computer viruses.

The challenges of delivering cybersecurity will be discussed by Dr. James Brink, radiologist in chief at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. He will explain how the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) of 1996 protects the medical records of U.S. citizens.

"My intent is to explain how this law has become more challenging to implement in the world of big data," he said, adding that to learn about artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, it may be necessary to share millions of patient records with external partners, and this creates more opportunities for a data breach.

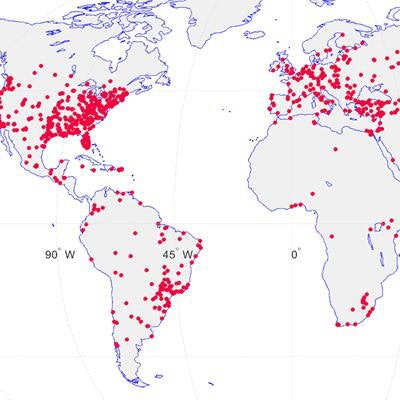

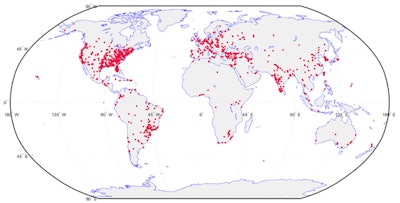

Radiology servers worldwide also are disturbingly vulnerable to cyberthreats. Dr. Oleg Pianykh, director of the medical analytics group in the MGH department of radiology, performed a worldwide security scan for DICOM vulnerabilities. The scan discovered an estimated 2,774 nonsecured hospital servers worldwide, half in the U.S., willing to share their data outside of their environment and unprotected by a firewall.

Clinical security vulnerabilities and hot spots, 2016: unprotected DICOM servers worldwide. Image courtesy of Dr. Oleg Pianykh.

Clinical security vulnerabilities and hot spots, 2016: unprotected DICOM servers worldwide. Image courtesy of Dr. Oleg Pianykh."When you manage protected health information in a world of machine learning, and then couple this with vulnerabilities, there's a substantive challenge to address as a profession," Brink said.

He admits there's no immediate easy solution to the big data challenge, but patient records can be protected by a variety of means. Although anonymization algorithms aren't perfect, they can be used as a risk mitigation strategy. Anonymized data can be maintained behind a firewall and external partners credentialed in data security before giving them access.

When it comes to protecting servers globally, Brink explained that the American College of Radiology is developing a security test to alert radiologists that their servers may be vulnerable.

At today's session, new data protection legislation in Europe will be discussed by Dr. Christoph Becker, professor of radiology and chair of the department of imaging at Geneva University Hospitals in Switzerland.

When the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force in May 2018, radiologists and radiology departments will have to observe new rules on protecting digital imaging data in daily clinical practice. For example, they will need to obtain explicit consent from patient before sharing their data, unless their national law allows for derogations. In addition, patients have the right to obtain information about their health record, including digital copies of images and diagnostic reports.

"We now have a Europe-wide legal framework for data processing, including imaging," he noted. "Depending on local/national law, radiologists have to comply with these requirements."

Becker adds that although some countries and hospitals are up-to-date, some organizational change will be needed for those not already in line with the regulations. There's also a need to find a compromise between protecting personal health data, forbidding processing without informed consent, and using big data to advance science.

The compromise between research and patient privacy is the focus of a talk by Erik Briers, PhD, a member of the Patient Advisory Group of the European Society of Radiology.

"Patients need to be in control of their data, but they do wish their data to be used, not only for their personal health but also in the context of research and clinical trials, which might benefit other patients," he said.

Briers explained that patients with complex diseases, such as cancer, often accumulate a huge volume of data throughout their treatment journey, such as pathology, lab, and radiology reports. It's essential that these reports are shared with treating clinicians to get the patient the right treatment.

However, although patients are generally happy for data to be shared for clinical research, they're often less happy for data to be given to an insurance company or a family member, because they might abuse the situation. An insurance or mortgage company could use the data to refuse a loan, for example. Employers may refuse to employ someone who's had a serious disease or, if the patient relapses later, they could dismiss them for not revealing an illness. For this reason, in France there is a law that -- after two or three years -- a serious disease will be forgotten, Briers explained.

He believes that patients have an altruistic sense that means they often want to share data above and beyond their medical reports -- provided it's used carefully. Diseases come from somewhere, and it can be useful for researchers to know people's employment records if, for example, all workers at a chemical plant have developed leukemia.

Originally published in ECR Today on 3 March 2018.

Copyright © 2018 European Society of Radiology