SINGAPORE – MRI plays a pivotal role in trauma cases by detecting lesions in the acute, subacute, and chronic phases of brain injuries, yet screening patients for implanted devices remains a primary safety concern, according to a leading expert.

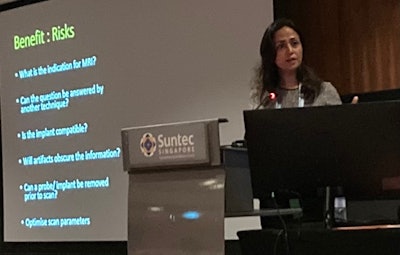

In a presentation May 6 at the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine meeting, Sumeet Kumar, MD, a senior consultant neuroradiologist at Singapore’s National Neuroscience Institute, discussed indications for MRI in head trauma cases, noting that MRI can detect small contusions often missed on first-line CT scans.

“In the acute phase, MRI is often done as a follow-up to a negative CT scan when the CT scan doesn’t explain the patient’s low consciousness as measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale,” she said.

These injuries may include so-called “diffuse axonal injuries,” or shearing (tearing) of axons when the brain shifts and rotates in the skull, and Kumar showed an example of this type of injury in a motorcyclist.

In the subacute phase, MRI can play a role detecting secondary injuries, such as raised intracranial pressure, brain herniation, arterial infarct, and infection, and in the chronic phase of head trauma, MRI is useful for detecting repetitive trauma in athletes and military personnel, such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, Kumar said.

In all trauma cases, however, the primary safety concern is screening for implants in patients, Kumar noted.

“Most commonly, we see patients with neuromonitoring devices such as ICP [intracranial pressure] monitors,” she said.

For instance, Kumar noted a case in a 20-year-old trauma patient with an MRI-compatible ICP monitor who experienced a significant thermal brain injury during an MRI scan. Heating due to the radiofrequency radiation in the MRI caused the tip of the transducer to melt, which results in injury to white matter at the site.

Upon further investigation, clinicians noted that scanning conditions, including the configuration of the transducer, MRI parameters such as the type of radiofrequency coil, and the specific absorption rate limit, deviated from the manufacturer’s recommendations, according to the case.

“It’s crucial to follow the manufacturer’s safety instructions,” Kumar said.

However, while manufacturers claim their devices are MRI-compatible, this may need to be taken with a grain of salt, Kumar added. She said in a recent survey of 12 manufacturers of orthopedic implants – which also need to be screened in patients before MRIs – 100% responded that they could not publicly say that their implants were completely MR safe, she said.

“This doesn’t say that MR can’t be performed in patients with implants, but it shifts the burden of the decision-making to the treating physicians … and clearly this is an area that needs more work,” Kumar said.

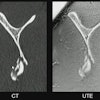

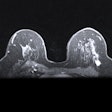

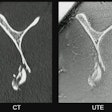

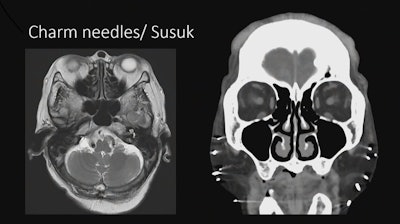

Imaging showing implanted charm needles in a patient.Image courtesy of Sumeet Kumar, MD

Imaging showing implanted charm needles in a patient.Image courtesy of Sumeet Kumar, MD

Kumar also noted a few safety concerns in cases with “local flavor,” such as patients with magnetic eyelashes and implanted subcutaneous charm needles. Charm needles are placed by shamans, so there is a spiritual belief associated with them related to enhancing a person’s beauty or energy, she said.

“And the bearer is not supposed to disclose it. They will not tell you that they’ve got them,” Kumar said.

A recent study determined that the needles are made mostly of gold, so they have been deemed safe in patients undergoing MRI scans, and Kumar said she and her colleagues have imaged multiple patients with these needles with no adverse events.

Lastly, MRI exams in trauma patients are safe and effective if clinicians ensure that the indication is appropriate, check the compatibility of implants and follow manufacturers’ guidelines, perform a thorough screening process, and above all, assess that the benefits to the patient outweigh the risks, Kumar concluded.