Radiologists can detect evidence of intimate partner violence before women disclose it and help facilitate earlier interventions to reduce cycles of abuse, according to a December 3 presentation at RSNA.

In a review of imaging from 1,322 cases, radiologic evidence of intimate partner violence was often present months or years before it was first self-reported, noted presenter Patrick Lenehan, MD, PhD, who led the study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Our overall takeaway and hope is that awareness of characteristic imaging patterns among radiologists can help us to detect [intimate partner violence] actually before disclosure and facilitate earlier interventions that can help break cycles of abuse for these patients,” Lenehan said.

Intimate partner violence is a serious public health concern, with recent U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates suggesting up to 40% of women in the U.S. have experienced some form of it -- physical, sexual, or psychological -- in their lifetime. While it can be difficult to detect in the clinical setting, previous work has demonstrated that radiologists can raise suspicion for physical intimate partner violence before it is self-reported, Lenehan noted.

In this study, Lenehan and colleagues aimed to validate this observation on an expanded cohort. The study population consisted of women who reported partner violence to Brigham and Women’s Hospital's violence prevention support program between 2013 and 2018 (“cases”; n = 1,322 patients with 28,872 imaging studies) and age- and race-matched women who did not report violence (“controls”; n = 5,520 patients with 48,637 imaging studies).

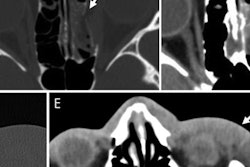

Two emergency radiologists reviewed each study and indicated whether intimate partner violence was suspected based on observed injuries and overall findings. Rates of suspected partner violence between cases and controls were compared using a crude odds ratio and Fisher-exact test.

In addition, the potential for early detection was assessed by summarizing the distribution of time between the date of initial self-reporting and the date on which a radiologist first raised suspicion of partner violence.

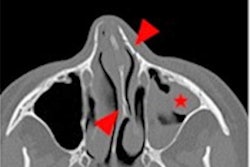

On review of the reports flagged as positive for injury, intimate partner violence was suspected by radiologists at any time for 158 of 1,322 cases versus 128 of 5,520 controls (12.0% versus 2.3%; p < 0.0001). Upper and lower extremity fractures were among the most common injury patterns seen on reports that preceded suspicion of partner violence for both groups, while facial fractures contributed disproportionately for cases (41 of 158 patients, 26.0%) compared to controls (10 of 128 patients, 7.8%).

In addition, among the 158 cases for whom partner violence was suspected by a radiologist, the median time between the date of first suspicion and initial self-reporting was 0 days, and 64 of these cases (40.5%) were suspected by radiologists at least six months prior to initial self-reporting.

"In patients with radiologic evidence of [intimate partner violence], the evidence was often present several months or years before it was first self-reported," Lenehan said.

Ultimately, the study builds on previous work by researchers at Mass General and the Trauma Imaging Research and Innovation Center (TIRIC) at Brigham and Women's Hospital. Lenehan noted contributions by Alex Kwon, a TIRIC research assistant and second author of the study.

“[This study] demonstrates the potential for radiologists to detect physical or nonphysical [intimate partner violence] and also provides some additional insight by including a control cohort so that we were able to assess specificity and apply this in a more translationally relevant way,” he concluded.

For our full coverage of this year’s meeting, visit our RADCast.