Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonitis:

Clinical:

LIP results from progressive alveolocapillary block due to nodular polyclonal lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphocytic infiltrate in the interlobular and interalveolar septae [12,15]. As an idiopathic disease, LIP is exceedingly rare and the condition is far more commonly a secondary disease in association with an underlying systemic disorder [9]. LIP is associated with: AIDS in infants and children (where it is the most frequently encountered pulmonary abnormality); and a variety of immunologic and autoimmune disorders such as Sjogren's syndrome (about 1% of Sjogren patients acquire LIP during the course of their disease [7]), pernicious anemia, myasthenia gravis, autoimmune thyroiditis [7], rheumatoid arthritis [7], systemic lupus erythematosus [7], and chronic active hepatitis [7]. LIP has also been described in association with multicentric Castleman's disease [3]. LIP can also occur as a late complication of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (graft versus host disease) [7,15].LIP occurs most often in the fourth to sixth decade of life and

women are affected more than men (2:1) [6,7]. Whites are affected

more than blacks [7]. Symptoms are usually insidious with mild

hypoxemia, cough, and progressive respiratory distress that

develop over a period of 3 or more years [9]. Approximately 60-80%

of affected patients have serum dysproteinemias- most commonly

polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia [7] or a monoclonal gammopathy

(usually IgM) [15]. Pulmonary function testing often reveals

a restrictive pattern [6]. Although LIP can sometimes be observed

on transbronchial biopsy, the definitive diagnosis requires

thoracoscopic or open lung biopsy specimens [7]. An exception to

this is in HIV-positive children in whom the radiologic appearance

and clinical symptoms are sufficient to support the diagnosis [7].

Treatment is with corticosteroids, although response is unpredictable, and treatment of the underlying disease [7,15]. Treatment usually results in improvement or resolution of symptoms in 50-60% of patients [6,7]. At least one third of patients are reported to have progressive disease despite therapy [15]. Approximately 33-50% of patients die within 5 years of diagnosis [7]. Malignant transformation is controversial- although it has been reported that approximately 5% of cases transform to lymphoma (low grade, B-cell) [7].

In children, the disorder is considered an AIDS-defining illness when confirmed histologically in patients under 13 years of age [7]. LIP can be seen in 16-40% of pediatric HIV-infected patients and is less common in HIV adults [2,7,13]. It has been suggested that LIP may be linked to the Ebstein-Barr virus [1,2,13]. The disorder has a chronic course, but a relatively good prognosis. LIP can occur at any stage of HIV infection, but usually occurs when the CD4 count is normal [13]. Paradoxically, if the radiographic features of the disorder improve, a decline in the patients immune status is often noted (coinciding with decreased CD4 counts) [4]. This change often heralds a clinical deterioration [4]. There is a variable response to treatment with steroids and otherwise healthy children can be observed [4].

Pseudolymphoma (now referred to as mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma or MALTOMA) represents a localized form of the disorder which is associated with Sjogrens syndrome that may occasionally progresses to non-Hodgkins lymphoma.

X-ray:

On CXR in LIP there is diffuse (but often lower lobe predominence), symmetric nodular (2-3mm) or reticulonodular pattern which may mimic airspace disease, but does not respond to antibiotic treatment. Medistinal or hilar adenopathy may occasionally be seen. The nodules can wax and wane in size and number [2]. Pleural disease and pleural effusion are rare (and if seen suggest another diagnosis) [5]. Airspace consolidation and bronchiectasis have been observed in pediatric patients with LIP and it is postulated that lymphocytic infiltration of the submucosa of the respiratory bronchioles leads to obstruction, inflammation, atelectasis, fibrosis, and finally dilatation [2]. Small cysts have also been described in patients with chronic LIP- possibly the result of small airway obstruction by peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltrate [2].

|

.LIP: This is a film on an 11 year old HIV positive male. The CXR reveals a diffuse, symmetric nodular pattern. The nodules were noted to wax and wane in size and number over time. |

|

|

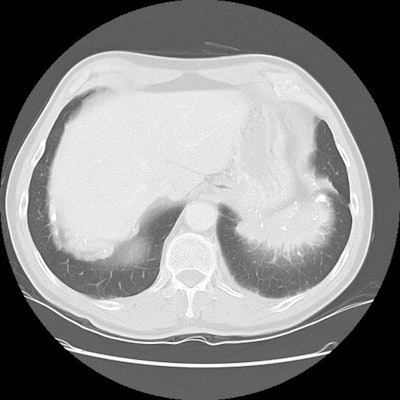

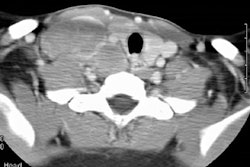

On CT findings can include small, 2-4 mm interstitial or

centrilobular nodules, ground-glass opacities, and ill-defined

centrilobular nodules [7,8,11]. Thin walled peribronchovascular

cysts can be found in up to 80-82% of patients with LIP

[5,9,11,14]- probably the result of the lymphocytic infiltrate

compressing bronchioles and subsequent post-obstructive

bronchiolar ectasia [7]. The cysts typically measure 1-30mm, have

a basal predominance, and are less numerous than seen in

lymphangioleiomyomatosis or EG [10,11]. Other authors indicate

that the cysts tend to have a peribronchial and subpleural

distribution [11].

|

.LIP: CT imaging in this adult patient with LIP revealed scattered ill-defined ground glass centrilobular nodules and extensive areas of ground glass opacity |

|

|

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiology 1995;197(1):53-58

(2) RadioGraphics 1996; 16: 1349-1362

(3) Radiology 1998; Johkoh T, et al. Intrathoracic multicentric Castleman's disease: CT findings in 12 patients. 209: 477-481

(4) J Thorac Imaging 1999; Pennington DJ, et al. Pulmonary disease in the immunecompromised child. 14: 37-50

(5) AJR 1999; Honda O, et al. Differential diagnosis of lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and malignant lymphoma on high-resolution CT. 173: 71-74

(6) Thorax 2001; Travis WD, Galvin JR. Non-neoplastic pulmonary lymphoid lesions. 56: 964-71. (No abstract available)

(7) Chest 2002; Swigris JJ, et al. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. A narrative review. 122: 2150-2164 (Review)

(8) AJR 2005; Marchiori E, et al. Pulmonary disease in patients with AIDS: high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. 184: 757-764

(9) Radiographics 2007; Mueller-Mang C, et al. What every

radiologist should know about interstitial pneumonias. 27: 595-615

(10) AJR 2011; Seaman DM, et al. Diffuse cystic lung disease at

high-resolution CT. 196: 1305-1311

(11) AJR 2012; Lichtenberger JP, et al. What a differetial a

virus makes: a practical approach to thoracic imaging findings in

the context of HIV infection- Part I, pulmonary findings. 198:

1295-1304

(12) AJR 2013; Nemec SF, et al. Lower lobe-predominant diseases

of the lung. 200: 712-728

(13) Radiographics 2014; Chou SHS, et al. Thoracic diseases

associated with HIV infection in the era of anti-retroviral

therapy: clinical and imaging findings. 34: 895-911

(14) Radiographics 2015; Sverzellati N, et al. American thoracic

society-European respiratory society classification of the

idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: advances in knowledge since

2002. 35: 1849-1872

(15) Radiographics 2016; Sirajuddin A, et al. Primary pulmonary lymphoid lesions: radiologic and pathologic findings. 36: 53-70