Dear MRI Insider,

A cousin of mine visited recently. It was a rare, sunny summer day in San Francisco and we opted to have lunch in the garden of a funky bistro. When we were led to the leafy back patio, my cousin looked around and inquired: "Could we sit someplace where there are less plants?"

At first I thought it was a bizarre request. But my cousin, a lifelong sufferer of asthma and its associated allergies, wasn’t merely being mercurial. For her, the threat of an asthmatic attack brought on by the abundance of foliage and flowers outweighed their aesthetic appeal.

More than 20 million Americans report having asthma, according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. In addition, there were 1.8 million asthma-related visits to U.S. emergency departments in 2000.

The AAAAI goes on to define the chronic disease as one in which "airflow in and out of the lungs may be blocked by muscle squeezing, swelling, and excess mucus. Patients with asthma may respond to factors in the environment, called triggers. In response to a trigger, an asthmatic's airways become narrowed and inflamed, resulting in wheezing and/or coughing symptoms."

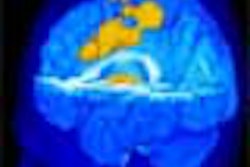

So what makes some people sensitive to those triggers? A team from the Center for In Vivo Microscopy at Duke University in Durham, NC, is hunting for the answer to that question, using dynamic MRI to simultaneously assess regional lung function and morphology. Currently testing their helium-based imaging protocol on mouse models, the group hopes to eventually sort out the complex circumstances that lead to asthma attacks. As an MRI Insider, you'll find the details here.

In related news, investigators from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville also used helium-driven MR studies to take a look at ventilation defects in asthmatics. To access this article, visit our MRI Digital Community.

If you are working on similar cutting-edge MR projects and would be interested in sharing your research-in-progress, please let me know at [email protected].