Now that virtual colonoscopy has been shown to detect significant colorectal polyps, the devil has taken refuge in the details. Indeed, radiologists who perform the CT procedure can cite any number of demons that will need to be exorcised before virtual colonoscopy is ready for the masses. And yet with new studies, new technology, and a growing body of clinical experience, investigators around the world are making progress toward resolving the many questions surrounding the procedure.

Technology will play a leading role. Will 3-D viewing methods eventually replace primary 2-D interpretation? How will the use of computer-aided detection affect sensitivity, specificity, and workflow? What are the limitations of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) schemes? And how will facilities handle larger numbers of patients while offering same-day colonoscopy when needed?

Lending considerable insight is Dr. Alec Megibow, a radiologist and virtual colonoscopy provider with New York University Medical Center in New York City. In a presentation at the 2002 Society of Computed Body Tomography and Magnetic Resonance’s Medically Principled CT Screening course in Boston, Megibow addressed workflow issues encountered when providing virtual colonoscopy services.

Assuming that colorectal cancer screening should be conducted, and that CT is capable of doing it, it's important to look at the challenges to operating a virtual colonoscopy program, Megibow said.

Patient acceptance comes first. "If we have this great test and nobody wants it, clearly it's not a great idea," he said. "Can CT colonography be performed in a clinically realistic time frame? And can the test be performed within a financially realistic reimbursement structure?"

Then there is the gap between the small number of people who are being screened for colorectal cancer and the large number of people for whom screening is indicated. The discrepancy will only grow as the population matures, he said.

"The (Centers for Disease Control) projects that the compliance target should improve from a rate of 37% -- that's how many people today access screening programs -- to 50% by the year 2010," Megibow said. Considering that many more people will be over age 50 in 2010 and therefore eligible for screening, he said, "this is going to be a significant manpower challenge."

Patient acceptance

Most studies of virtual colonoscopy's performance now include questionnaires to assess patients' "satisfaction, discomfort, embarrassment, anxiety, and a whole variety of parameters people feel can characterize the patient's experience at the CT scan," Megibow said.

For example, in a recent study by Dr. Maria Svensson from Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Göteborg, Sweden, 111 patients underwent virtual colonoscopy followed immediately by conventional colonoscopy. Among patients who preferred one exam over the other, 82% preferred VC (P < .00001). Overall, 69% with a preference considered colonoscopy to be more difficult (P = .002).

Virtual colonoscopy was considered "not painful" by 57% of 108 patients compared with 26% for colonoscopy, and more patients rated their pain higher during colonoscopy than during virtual colonoscopy (95% CI: 30%, 56%).

"Discomfort from air filling of the colon was the major complaint" of virtual colonoscopy, Megibow said (Radiology, February 2002, Vol. 222:2, pp.337-345).

A Belgian study found that 28% of patients preferred virtual colonoscopy even though they considered it equally or more uncomfortable than conventional colonoscopy. These patients preferred the faster procedure time (17 patients), lower physical challenge (14 patients), and the lack of sedation (12 patients) in virtual colonoscopy (European Radiology, June 2002, Vol. 12:6, pp.1410-1415).

Carbon dioxide rather than air insufflation has also been shown to reduce pain and discomfort in virtual colonoscopy, Megibow said, but CO2 adds to procedure time.

"The bottom line is that acceptance rates equal or exceed conventional colonoscopy," Megibow said.

Procedure time

"Can (virtual colonoscopy) be performed within a clinically realistic time frame, where the facility can operate efficiently, and credible diagnostic results can be maintained?" Megibow asked.

Breaking the procedure down to its component parts can help radiologists analyze workflow, he said. Facility time, exam time, reconstruction and data transfer time, diagnosis and reporting time -- each step offers opportunities to improve workflow to determine the reimbursement levels needed to operate profitably.

Posting patient questionnaires and forms on the Web can save time in the office, Megibow said. Most patient concerns have to do with the bowel cleansing that precedes the exam, an issue that also affects the facility's throughput. Providers must ensure that there are enough dressing rooms and restrooms for post-procedural use -- something Megibow said his own group must contend with whenever patient volumes spike.

"Every time (Today host) Katie Couric goes on TV in New York and (NYU's Dr. Michael Macari) is interviewed, we get this huge influx of patients," Megibow said.

Exam time is variable, and includes the patient getting on and off the table, air insufflation (about 40 puffs), and 2 CT image acquisitions, supine and prone. With a lot of experience, he said, it can all be done in 10-12 minutes.

Reconstruction and transfer time

On NYU's Volume Zoom scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen Germany), radiologists use a 4 x 1-mm dataset for a virtual colonoscopy exam. This results in about 350 images per acquisition, or 700 images for both prone and supine acquisitions. Reconstruction, at 1 second per image, takes about 11.5 minutes per exam.

Seven hundred 512 x 512 images means about 512 MB (1,400 megabits) of data per study that must then be transferred to the workstation, Megibow said. A study takes 15-20 minutes to transfer on a T1 line (1.5 MB per second) or 2-5 minutes on an Ethernet line (10 MB per second).

"If you are in a facility directly where the scan is being performed, and you have instantaneous access, then this transmission time disappears," he said. "But many service paradigms revolve around having outlying sites shipping data to a central site, and you have to be cognizant of the type of transmission line you're going to be using."

Diagnosis and reporting

The radiology literature shows a wide variability in the time required to diagnose and report virtual colonoscopy results, Megibow said.

In a recent study at the Washington University in St. Louis, for example, 4 experienced academic radiologists averaged 15-23 minutes to read and report each study (Radiology, November 2002, Vol 225:2, pp.380-390).

A Belgian study found that interpretation times ranged from 17 to 47 minutes depending on reader experience (European Radiology, June 2002, Vol. 12:6, pp.1405-1409).

"The reading time really occupies the single largest chunk of the workflow," Megibow said, and so offers the biggest potential time savings.

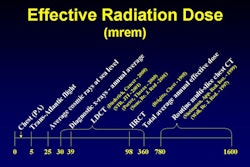

One can pare about 20 minutes from each case by using thicker sections, which also reduces the radiation dose, Megibow said. "But one has to question, even as we lower the dose further and further, (if) we will be preserving sensitivity and specificity to levels where we're operating right now."

Faster reading times will also be important when same-day conventional colonoscopy is implemented to remove significant polyps detected with virtual colonoscopy, Megibow said. Same-day colonoscopy exams are thought to be essential if virtual colonoscopy is to eventually screen large numbers of low-risk patients.

With same-day conventional colonoscopy, radiologists at his facility will no longer be able to batch-read VC results, Megibow said. The upside is that same-day exams will spur the development of new strategies to reduce reading times.

Primary 2-D vs. 3-D interpretation

Images can be read primarily in 2-D with 3-D endoluminal views for problem solving, or the other way around. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, its proponents and detractors.

"With the 2-D review, you can look at the prone and supine (images) together, and you have a much better chance of seeing the whole colon," Megibow said. This method is improving, with faster computers, and software that draws a line through the central lumen of the colon.

Megibow said he prefers the 2-D primary read, referring to 3-D continuously to help distinguish polyps from folds. Still, he said, in 2-D reference points are harder to track, as they roll and disappear and change location with regard to anatomic landmarks.

Three-dimensional review works better for problem solving, better for navigation, and has the ability to cross-mark focal abnormalities and reference them to the axial images, he said.

"But (with 3-D) you're worried about complete evaluation of the (colonic) surface, blind spots ... we miss a whole lot of things just like colonoscopists. And (3-D) is fatiguing ... the thing is spinning, it's turning, it's spiraling. My eyes get tired."

Not only does 3-D present ergonomic issues that have yet to be resolved, it provides no textural information that can help the radiologist look for air bubbles that distinguish stool from polyp, Megibow said.

CAD challenges

CAD systems rely on algorithms that assess shape, curvature, and texture to find polyp candidates, then eliminate some of the false positives, Megibow said. But CAD is a tricky proposition. The systems will need to be fine-tuned with very large case databases in order to achieve good sensitivity and specificity for polyps and colorectal cancers, he said.

For example, CAD systems will have to be adept at seeing through so-called polyp camouflages such as stool, folds, and the ileocecal valve. CAD will have to deal with nonrigid registration of prone and supine images that makes it difficult to line up colonic segments one on one.

The large databases underlying CAD schemes will need to include cancers whose morphology is less spherical than the adenomatous polyp model, including flat lesions. Unfortunately, Megibow said, building in these abilities could end up diluting CAD's ability to distinguish polyps and cancers from normal structures.

Finally, he said, studies show that about 10% of colonic segments are simply not well distended. Image noise is often a problem, especially with low-dose protocols. "This can be problematic," he said. "If this is difficult for us to see, the computer systems are going to have much more difficulty recognizing shapes."

Still, virtual colonoscopy has been demonstrated to be an acceptable method of detecting colorectal cancers. "The biggest opportunities are in reducing reading times, and computer-assisted diagnosis may offer significant benefits," Megibow concluded.

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

January 15, 2003

Related Reading

Multiobserver performance trial assesses utility of screening VC, November 27, 2002

CAD scheme offers faster, more accurate virtual colonoscopy, November 6, 2002

Medicare boosts outpatient mammography and colonoscopy payment rates, November 5, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com