During his four months at Balad Air Force medical center in Iraq, some 60 miles north of Baghdad, the trauma cases treated by Dr. Jason Huang bore little resemblance to what he experienced at the Center for Neural Development and Disease at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

Many of the U.S. soldiers' head injuries were cases that Huang had never seen before in civilian practice in the U.S., even in cases of gunshot wounds. "There is no comparison to the degree of injuries we saw over there," said Huang, a neurosurgeon and assistant professor of neurology.

Huang and the only other neurosurgeon in Iraq saw more than their share of severe head trauma caused by so-called improvised explosive devices, or IEDs. "The weapons are unconventional," he added. "They don't shoot at you. The majority of U.S. casualties are from IEDs."

In addition to military personnel, the base also treated Iraqi civilians. "[They] became a significant portion of your practice," Huang said, "because any time there is collateral damage or a suicide bombing and mass casualties, most of the Iraqis came to us. We are the last line of defense."

The Balad hospital is a level I trauma center. Huang described the medical equipment at the base as very good, allowing the OR personnel to adequately handle emergency trauma surgeries. There are two four-slice CT scanners (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) at the hospital and there is 24/7 radiology coverage, but no MRI scanner.

|

| Clinicians and Balad staff prepare a head trauma patient for a CT scan. All images courtesy of Dr. Jason Huang. |

"For us, we had to adapt our practice style to the theater, because all we had were the CT scanners," Huang said. Cases such as a brain tumor which required more extensive care and imaging technology were transferred to a military hospital in Germany.

During his deployment from January to April of this year in Iraq, Huang saw approximately 300 trauma cases per month at the Balad hospital. During that time, he and his fellow neurosurgeon surgically and nonsurgically treated approximately 1,200 soldiers, which included coalition forces from other countries and Iraqi soldiers.

Huang noted "a deep decline" in U.S. casualties during his tour, but the trend did not lessen the volume of patients at Balad. While the number of head injuries to U.S. soldiers was trending down, head injuries for Iraqi soldiers was increasing.

|

| Drs. Jason Huang (left) and Major Richard Clatterbuck, the other neurosurgeon in Iraq during Huang's four-month tour, collaborate in the operating room. |

The biggest challenge for surgeons at Balad was the undetected injury. An initial CT scan may show that the brain looks relatively normal, in terms of subdural hemorrhage or contusion, but what is sometimes not seen is a soft-tissue injury, which may be extensive.

"An explosion causes quite devastating injuries. On the surface, it causes severe soft-tissue injuries," Huang said. "Our imaging studies may show the devastating picture of fragment injuries of the brain. You can see multiple fragments within the brain on the CT scan, but without the fragment injury, the imaging study can be deceiving."

With the limitations of CT, soldiers may develop headaches, memory problems, other cognitive deficit symptoms, and depression as a result of head trauma, despite an initial CT scan that was deemed negative.

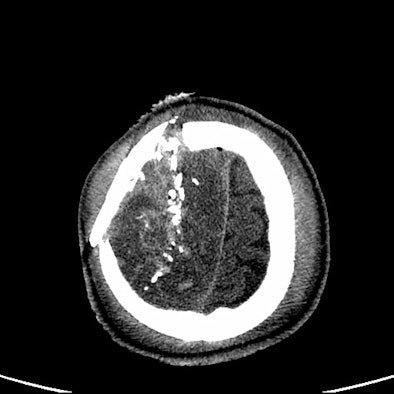

|

| Image of a U.S. soldier whose CT scan did not reflect his severe blast head injury. Neurosurgeons performed a craniectomy, even though the CT scan did not show midline shift. |

|

| Image of a second U.S. soldier whose head CT scan did reveal the extent of damage from head trauma. |

"Blunt injury is very different from anything we have seen in previous wars. The CT scan doesn't tell you the degree of injury from the blast itself, but CT is still good for any hemorrhage," Huang said. "There is no hemorrhaging or no contusion, so there is no imaging evidence of brain injury of those soldiers, but then you examine them later and they are not normal."

U.S. soldiers who exhibit those conditions are sent to Germany for further evaluation by MRI. "There is evidence that if you follow-up soldiers, an MRI scan may show additional injury, but you won't see that on CT scan," Huang said.

Experience gained

As for applying his time in Iraq to his practice at the University of Rochester Medical Center, Huang said the "most important thing I learned was the teamwork and cooperation among the different specialties. Over there, there are no residents working to assist. Sometimes, a craniotomy is a two-man job."

Huang was aided at times by a thoracic surgeon who would assess the craniotomy cases.

"If you work well across the different disciplines and with nursing and other staff members, it will improve outcomes," he emphasized. "That is one of the most valuable lessons from my military experience."

The teamwork and dedication of the medical personnel paid dividends. Huang said the facility had a 98% survival rate for U.S. soldiers going through the hospital.

By Wayne Forrest

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

October 15, 2008

Related Reading

Routine CT scanning is most cost-effective for minor head injuries, March 7, 2008

256-slice CT brings new possibilities in head imaging, May 28, 2007

MRI, CT remain front and center in head trauma imaging, April 18, 2007

Brain damage in boxers occurs long before symptoms, November 15, 2002

Imaging is rarely definitive in concussion, February 21, 2002

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com