The number of CT scans performed on children with head injuries who are at intermediate risk of traumatic brain injury could be cut in half by putting many kids under observation rather than scanning them immediately, according to a new study of more than 40,000 children published in Pediatrics.

Considering the risks associated with CT, especially in younger patients, appropriate and safe guidelines are needed to reduce the number of inappropriate head CT scans. The results of the new study indicate that a period of observation can spare children unnecessary radiation without missing important brain injuries (Pediatrics, May 9, 2011).

Only a small percentage of children with blunt head trauma have serious injuries, but many are scanned with CT immediately upon presentation to the emergency department. With an eye toward heightened radiation risks in children, Dr. Lise Nigrovic, of Children's Hospital Boston, and colleagues wanted to find out if delaying CT scans in patients with mild head injuries led to more serious problems in the group that waited. It did not.

Even though the rate of clinically serious findings was similar in patients who were observed versus those who went directly to CT, "the overall rate of CT was 4% lower in the observation group," Nigrovic told AuntMinnie.com in an interview.

As might be expected, children who were observed before the CT decision was made were more likely to have clinical factors that would place them in the intermediate-risk group than children who were not observed. But when adjusted for the severity of head injury and the practice style of different hospitals, the rate of scans for observed patients "was about half -- 53%" the rate for similar nonobserved patients, Nigrovic said.

Nigrovic co-led the study with Dr. Nathan Kuppermann, from the University of California, Davis, and 23 other institutions in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). The prospective analysis of children with minor blunt head trauma assessed the clinical impact of different CT strategies -- waiting to scan or not waiting -- on CT use and outcomes.

The authors compared CT use rates between children who were observed and those who went directly to CT, using a generalized estimating equation model to control for hospital clustering and patient characteristics.

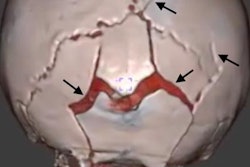

Clinically important traumatic brain injury was defined as an intracranial injury resulting in death, neurosurgical intervention, intubation for longer than 24 hours, or hospital admission for two nights or longer. Patients with scores of 14 or 15 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) were enrolled at presentation to the emergency department within 24 hours of the traumatic event.

Excluded were patients with trivial injuries and without signs of traumatic brain injury (TBI), penetrating trauma, or comorbidities. Medical records were analyzed to assess outcomes, including the rate of CT scan use and the frequency of clinically important TBI.

"Observation is for children who aren't at the lowest risk and aren't at the highest risk" of TBI, Nigrovic said. Rather, observation is for those in the middle-risk groups -- who don't appear normal but whose injury isn't obviously severe -- for whom observation can be very helpful, she said.

Among the 40,113 children studied, the rates of clinically important TBI were similar between children who were observed prior to CT (0.75%) and those who were not observed (0.87%), even though CT use was 3.9% lower in children who were observed (31.1% versus 35.0% for nonobserved patients).

After adjustment for hospital and patient characteristics, the difference in CT use remained significantly lower among patients who were observed, with an adjusted odds ratio for obtaining a CT scan in the observed group of 0.53 (95% confidence interval: 0.43-0.66).

"I think what's driving this observation strategy is the recognition that CTs have their own associated risks, and although that risk is long-term, the child has many years ahead of him so those risks are experienced over a long lifetime, and you don't want to do unnecessary scans," Nigrovic said.

The results showed that observation before making a decision regarding CT use was common (14% of patients) and was associated with approximately one-half the adjusted odds of obtaining a CT scan compared with nonobserved patients. In addition, the rate of CT use was lower for patients whose symptoms improved during the period of observation.

For patients who, after observation, had either no initial headache or improved headache, no vomiting or improved vomiting, or GCS scores of 15, the CT rate was 976 of 4,010 (24.3%), compared with 13,837 of 40,113 (34.5%) for the whole population -- a significant reduction considering the at-risk population.

"Although the risk of clinically important TBI in this intermediate-risk group is non-negligible, cranial CT itself presents radiation risks," the authors noted. The observation strategy is important, they added, because "it allows CT to be used selectively for children who are not in a high-risk group for clinically important TBI and whose symptoms progress or do not resolve over a period of observation."

In rare cases, children with apparently minor blunt head trauma will initially be asymptomatic but then will clinically deteriorate after a period of time, typically due to expanding intracranial hematoma or progressive cerebral edema. However, recent studies suggest that the rate is extremely low.

"These studies offer additional evidence that observation after minor head trauma provides an important management strategy for a subset of children with apparently minor blunt head trauma by allowing symptom progression or resolution in a monitored environment," the group noted.

As for study limitations, the investigators were unable to determine the cost differential, if any, between the patients who were observed and those who were not.

More studies are also needed to determine the appropriate duration of clinical observation. Observation times were not measured in this study, though "common practice is between four and six hours after an injury," Nigrovic said. Both costs and observation time "need further work," Nigrovic said.

Have the results changed the practice of CT use after pediatric head trauma at Children's Hospital Boston?

"At our institution, [observation] is a commonly used practice; in my own department, it's something I do commonly and I think that my colleagues do as well," she said. "It's not part of a formal protocol to date. But I think this is likely to be used more commonly over time across the country as we increasingly become concerned about radiation exposure."