Maybe they're perfectionists: A new study from McGill University in Montreal found that radiologic technologists wanted to repeat far more head CT scans than radiologists, who seem more willing to put up with image noise and artifacts.

In research that included more than 100 repeated head scans, CT technologists not only rated mean image quality lower than radiologists, they opted to repeat about half of a group of head scans that were filled with artifacts; in contrast, only one-fifth of scans would have been repeated by radiologists. Interobserver agreement was moderate in both groups but slightly higher among radiologists.

"When presented with the exact same images, our techs wanted to repeat almost 30% more than our average staff or fellows," said third-year radiology resident Dr. Jaron Chong in a presentation at the RSNA 2012 meeting.

Fallout from dose accidents

The idea for the study came about in the wake of news reports in 2010 regarding excessive radiation doses at hospitals in California, Chong said. The team performed an audit that plotted dose outliers among the 40,000 or so scans performed at the institution that year.

"We wanted to prove that these events weren't happening at McGill," Chong said.

After reviewing the top 252 exams performed at the hospital, the group found that three categories stood out: random events, interventional procedures, and, oddly enough, CT head studies, he said. In all, 150 exams had repeated series from the base of the skull to the posterior fossa. Among them, 40% were successful and 60% were unsuccessful, "which begs the question: What was the point of those repeats?" he said.

It turned out that many of the dose outliers were due to repeated partial volumes of CT head scans secondary to image artifact, he said. But the image review showed that many of the repeated series were minimally diagnostic, were centered at the posterior fossa, and often involved radiosensitive tissues such as the eye lens.

The researchers therefore decided to test the threshold for bad studies between technologists, staff, and fellow-level radiologists. They picked a "greatest hits" collection of 122 of the worst head scans at McGill.

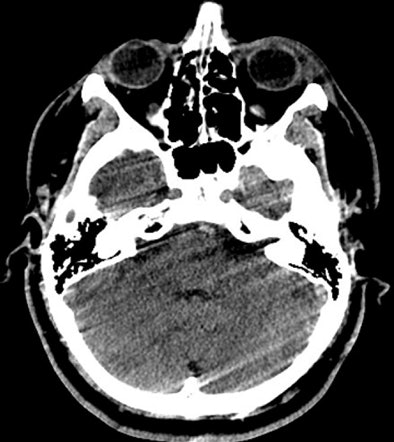

|

| One slice of a posterior fossa scan that 75% of technologists and none of the radiologists chose to repeat. All images courtesy of Dr. Jaron Chong. |

"We took out the noisiest single slice from each exam, we randomized and anonymized them ... and sent them as a quiz to our technologists and staff, asking them two questions: How would you rate this study? And, if you saw this scan at the console, would you repeat it?" Chong said.

Randomized, blinded exams were given to eight CT technologists, two board-certified radiologists, and one neuroradiology subspecialist fellow. The readers were asked to rate image quality (1 = worst, 5 = best) and state whether they would repeat the acquisition in a clinical trauma setting. Comments were also solicited from the readers after the exam to gain insight into the rationales of staff, fellows, and technologists.

Picky, picky

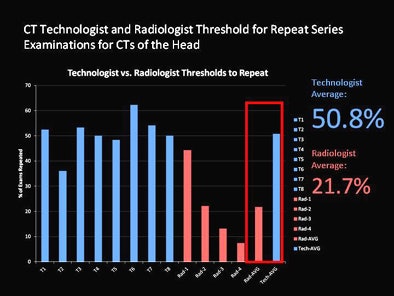

The results showed that CT technologists rated image quality lower than radiologists did (3.2 for technologists, compared with 3.7 for radiologists). The technologists opted to repeat acquisitions an average 50.8% of the time (range, 36% to 62%), versus 21.7% (range, 7.4% to 44.3%) for the radiologists. Therefore, the technologists opted to repeat the exam 30% more often than the radiologists and fellow.

"Now, some would look at this and say it's horrible -- it really isn't -- but 30% is where we can do better, and exactly where we can get our population dose savings from," Chong said.

|

| Presented with the exact same images as radiologists and blinded to diagnosis, context, or history, technologists wanted to repeat almost 30% more than the average radiologist or fellow. |

Digging a little deeper into the data, technologists continued to be two to three times more likely than radiologists to ask for a repeat scan, whether it was the first, second, or final image acquisition for a given patient, he said. And there was some relationship between subjective image quality and the desire to redo a scan, but multiple decisions to repeat scans were applied even to images scoring 3.0 or higher.

Overall kappa interreader agreement was moderate in both groups but slightly higher between the radiologists (0.52 versus 0.45), and there was increased consensus at the higher end of the image quality scale about whether or not the scan needed repeating, Chong said.

"It's important to understand what we are measuring here: individual preferences of our own technologists and our own staff in artificial simulations," he said. Clearly, the results don't apply to all situations and all hospitals, and the results don't mean that radiologists were too lenient in repeating exams.

"If you look back at the quality of the exam, most of those repeat series were really artifact-filled, and what we felt was happening was that there was discordance between the processes of the technologist and the processes of the radiologist," Chong said. "The technologist was trained to get the perfect image, and the radiologist to make the right diagnosis, and in the absence of specific guidelines each group focused on what it does best."

More should be done with these preliminary results, Chong said, such as showing the entire image series, being more transparent with the clinical information, and doing more testing of residents and nonradiological staff.

"But this remained an interesting project for me because by running this quiz, we were running a psychological test; we were looking at human behavior and trying to measure it," he said. "And we learned a bit more about ourselves."

Image quality is important, but overemphasizing it can encourage the decision to repeat too many acquisitions, he said. Technologists would benefit from clear and specific guidelines regarding repeat scans.

The debriefing section of the study was the most informative part, Chong said, as it offered an opportunity to really probe the motivations of the participants. And it appears they were motivated only by the desire to produce a diagnostic image.

"The real story here is that the road to higher dose is paved with good intentions," he said. "Intentions are not something you can always measure, but they are something we should probably talk a lot more about."