Breast abscesses can occur for a variety of reasons. In lactating women, puerperal abscesses can result from delayed mastitis diagnosis and treatment. Women who have undergone breast augmentation may experience similar problems soon after surgery.

Less common is postsurgical seroma, a complication of lumpectomy and radiation therapy. However, these cases do arise, and to treat them, women's imaging specialists from Stanford University in Stanford, CA, recommend ultrasound-guided catheter drainage.

"Delayed breast abscesses usually occur months after treatment.... The delay of infection suggests that the seroma cavities are initially sterile, but subsequently are subject to bacterial contamination," wrote Drs. Juno Min, Robyn Birdwell, and Joan Frisoli, Ph.D., in the Journal of Women's Imaging (June 2004, Vol. 6:2, pp. 81-84).

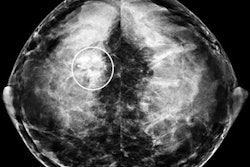

The group described their technique in a case report of a 55-year-old woman who underwent breast-conserving surgery after being diagnosed with pleomorphic calcifications in the right breast. Five months after the surgery, the patient developed erythema, warmth, tenderness, and swelling at the lumpectomy site in the subareolar region of the right breast. An ultrasound exam demonstrated a "complex thick-walled fluid collection, worrisome for an infected cavity."

For the outpatient drainage procedure, the patient was positioned in a supine position and the infected cavity was sonographically localized using a 7-12-MHz linear transducer (Logiq, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). A metal stiffener was placed inside a 10 French Navarre catheter in order to penetrate skin thickened by radiation. Purulent fluid was aspirated and the cavity was flushed with 10 mL of saline. The catheter was then attached to a gravity drainage and affixed to the patient's skin. The patient was sent home on a course of oral clindamycin.

The patient returned the next day with about 20 mL of purulent drainage from the catheter, the group stated. A 2.8-cm abscess cavity, collapsed around the catheter tip, was seen on ultrasound. The woman was symptom-free six months after the procedure.

The authors touted their method as a way to avoid surgical intervention. It is also less time-consuming, has a lower recurrence rate, and is less expensive. The technique did not require conscious sedation or general anesthesia, nor was the patient expected to change wound dressings during the recovery period.

But both Min and Birdwell stressed that postlumpectomy/radiation breast abscesses are fairly rare, so the procedure is not done routinely at Stanford.

"According to one of our breast surgeons, this is only the second case she has seen in over 10 years," Min wrote in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com. "Thus far, this is the only case at our institution that we have attempted to drain with an indwelling catheter, but we would certainly consider this option for any future cases. With the increase in breast-conserving therapy, these complications may become more prevalent in the future."

Still, the group's results dovetail with earlier reports on the success of ultrasound-guided drainage. Radiologists from Sweden used ultrasound-guided procedures on breast abscesses in 43 lactating women. They found that aspiration was best for abscesses smaller than 3 cm, and catheter drainage was best for abscesses of 3 cm or larger (Radiology online, July 29, 2004).

However, the procedure may also be possible without indwelling catheters. Radiologists from Pereira Rossell Hospital in Montevideo, Uruguay, studied the feasibility of treating breast abscesses with sonographically guided aspiration, irrigation, and local instillation of antibiotics. Their patient population consisted of 73 women with 73 abscesses. A 14-gauge needle was used under ultrasound guidance. The abscess was aspirated and the cavity irrigated with saline until the aspirate returned clear. One gram of cephradine was injected into the abscess. The patient was prescribed a course of oral cephradine as well.

Drs. Francisco and Felix Leborgne reported that 96% of their patients completed treatment and were cured with this procedure. The treatment failed, requiring surgical drainage, in three patients.

"Our study has shown that a high rate of success is achieved with percutaneous aspiration and careful irrigation of breast abscesses, and that the placement of indwelling catheters is unnecessary," they wrote (American Journal of Roentgenology, October 2003, Vol. 181:4, pp.1089-1091).

Still, the Uruguayan method may not be successful for dealing with abscesses 3 cm or larger. Min pointed out that complex abscesses will often not resolve with simple percutaneous drainage, and may still necessitate placement of an indwelling catheter.

"We have not used this (indwelling) treatment because the more standard approach (aspiration, etc.) typically works," Birdwell explained in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com. "However ... for those abscesses greater than 3 cm, this (indwelling) approach may be necessary if there is no response/worsening following multiple aspirations."

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 2, 2004

Related Reading

Strict attention to detail enhances sensitivity of breast US, April 17, 2003

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com