The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) has highlighted a study that shows cardiac PET scans can help identify people at risk for Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia.

In a study of 34 people at risk for these diseases, NIH scientists used PET scans to show that individuals with low uptake of F-18 dopamine PET radiotracer in the heart were highly likely to develop Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia (LBD) during long-term follow-up, compared to individuals with the same risk factors but with normal radioactivity.

Significantly, the research supports a “body first” progression model for the diseases, the researchers suggested.

“We think that in many cases of Parkinson’s and dementia with Lewy bodies the disease processes don’t actually begin in the brain,” noted principal investigator David Goldstein, MD, PhD, of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), in a news release.

Essentially, the idea is that the loss of norepinephrine in the heart predicts and precedes the loss of dopamine in the brain in Lewy body diseases, Goldstein said.

Both Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia are brain diseases caused by abnormal deposits of the protein alpha-synuclein, which form clumps known as Lewy bodies. Earlier work by the group found that people with Lewy body disease had severe depletion of cardiac norepinephrine, which is normally released by the nerves that supply the heart.

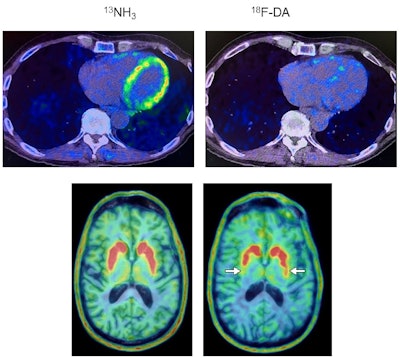

Heart and brain PET scans from a study participant who developed Parkinson’s disease support a “body first” progression. The top pair of PET scan images show low F-18 dopamine-derived radioactivity in the heart (right, with N-13 ammonia PET scan on left). Later, brain scans showed a loss of dopamine-producing neurons and the individual developed symptoms of the disease. Image courtesy of the National Institutes of Health.

Heart and brain PET scans from a study participant who developed Parkinson’s disease support a “body first” progression. The top pair of PET scan images show low F-18 dopamine-derived radioactivity in the heart (right, with N-13 ammonia PET scan on left). Later, brain scans showed a loss of dopamine-producing neurons and the individual developed symptoms of the disease. Image courtesy of the National Institutes of Health.

In the present study, 34 people at risk for Parkinson’s underwent cardiac F-18 dopamine PET scans every 18 months for up to about 7.5 years, or until they were diagnosed with the disease. Participants had three or more Parkinson’s risk factors, which included a family history of the disease, loss of sense of smell, dream enactment behavior, and symptoms of orthostatic intolerance, such as light-headedness upon standing.

Out of nine individuals with low cardiac F-18 dopamine-derived radioactivity at their first scan, eight were diagnosed later with Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia, according to the findings.

Additionally, only one out of 11 participants with normal initial radioactivity developed a central Lewy body disease. All nine participants who developed a Lewy body disease had low radioactivity before or at the time of diagnosis, the researchers found.

“Cardiac F-18 dopamine PET highly efficiently distinguishes at-risk individuals who are diagnosed subsequently with a central LBD from those who are not,” the researchers wrote.

Ultimately, using these PET scans to identify people with preclinical Lewy body diseases could enable testing of preventative approaches such as lifestyle modifications, dietary supplements, or medications, the researchers suggested.

“Once symptoms begin, most of the damage has already been done,” Goldstein said. “You want to be able to detect the disease early on. If you could salvage the dopamine terminals that are sick but not yet dead, then you might be able to prolong the time before the person shows symptoms,” he said.

The full article was published recently in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.