This is the second and final installment of a white paper contributed by Dr. Stefano Ciatti and colleagues at the Studio Ecograficao Dott. Stefano Ciatti in Prato, Italy. It explores the role of 3-D ultrasound in shaping the perceptions of pregnant women toward the developing fetus.

Results of the Emas S test

Following the obstetric examinations and 3-D ultrasound, the women completed a follow-up questionnaire, the Emas S test. According to the results of this questionnaire, only 24% of the women in our study were suffering from higher-than-normal anxiety levels in response to their situation (40-60 points).

- 38 women presented with a normal level of anxiety.

- 12 women presented with a higher-than-normal level of anxiety than normal.

- 1 woman presented with a lower-than-average level of anxiety.

Information revealed about the women during the interview:

- 42 are married.

- 9 live with a partner.

- 40 women attended the examination accompanied by their husband/partner.

- 4 women attended the examination accompanied by someone else (mother, other relative, obstetrician, or midwife).

- 7 women attended the examination alone.

The actual pregnancy:

- 43 women said that they had really desired the pregnancy.

- 8 women said that they had not sought the pregnancy but that it was well accepted.

Disturbances of pregnancy:

- 3 women were suffering from gestational diabetes; 2 of these 3 women had been admitted frequently to hospital. The third, even though she had suffered a hemorrhage, did not want to leave her other child and had refused to be admitted to the hospital.

- 1 woman had suffered from a urinary tract infection.

- 1 woman had hematomas at the borders of the gestational sac.

- 2 women (in the third trimester) were still suffering with persistent vomiting: one of these women had been admitted twice to hospital with dehydration.

- 1 woman was being followed with serial ultrasound scans in the assessment of a cystic hygroma.

Previous pregnancy interruptions:

- 1 woman had undergone a voluntary pregnancy termination.

- 6 women had suffered a previous spontaneous miscarriage.

The study cohort came from sociocultural backgrounds with medium-to-high levels of education. The majority of these women are employed or work for themselves. As a result, these women were nearly all over 30 years of age and greatly desired their first pregnancies.

The extended education delays participation in the workforce, and as a result delays economic autonomy. The system in Italy tends to protect the young from confronting life, and as such delays effective maturation. On the other hand, half of these youths succeed in obtaining a university degree, which they experience as a means of social redemption in addition to increasing their economic well-being.

These women were not satisfied with previous ultrasound examinations provided by other healthcare services, and had actively sought to have a repeat examination in our clinic. They claimed that the examinations were rushed, and that the doctors gave them little or no explanation during scanning. They had great difficulty in understanding and following the pictures of the fetus on the screen. One woman described her experience by saying "There was no time to ask questions; I thought that the doctor had temporarily gone away but he never came back."

|

| Figure 7, a 3-D ultrasound image of the fetus at 13 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

Limited time, the absence of explanation, and the lack of time for communication in previous experiences were the themes that came to light during our interviews. Some women justified their previous experiences by saying that a busy work day prevented the doctors from doing more.

Others expressed a great sense of frustration: they described being treated as a body part under examination and not as a human being. Their perception of the ultrasound examination resulted simply in a black-and-white printed report and one or two unclear printed images.

|

| Figure 8, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetus with hands in front of face at 21 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

As a result, many of the women expressed a critical evaluation of their previous experiences demonstrating their capacity to express their dissatisfaction and their ability to search for an alternative. In fact, 31% of the cases came from outside the city of Prato.

Despite the fact that the majority of these women were over 30 years of age, they were all accompanied by their husbands, partners, or other family members. The obstetrical ultrasound examination changes the pregnancy from being something "feminine" into something for the couple and the whole family.

|

| Figure 9, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetal foot at 28 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

According to a study conducted by Berwick and Weinstein, 44% of parents who present for an obstetrical ultrasound examination are not interested in something medical: the authors maintain that the parents look for information which is different to that which interests the doctor (Medical Care, 1985, Vol. 23:7, pp. 881-893). An article published by Stephens, Monfalcon and Lane reveals that more than one-third of the women who have an obstetrical ultrasound do so simply to be reassured (Journal of Family Practice, 2000, Vol. 49:7, pp. 601-604). Filly explained the situation: "This woman is having a sonogram for reassurance. Her husband, children, and parents are with her. There is a party atmosphere. The videotape is rolling ..."(Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2000, Vol. 19:1, pp.1-5).

Accepting to have an obstetrical ultrasound examination performed with state-of-the-art instrumentation requires the mother-to-be to entrust her care to an expert in order to be reassured. This situation can sometimes activate a state of anxiety as to the well-being of the fetus on the part of the future mother. Therefore, the recognizable pictures produced by 3-D ultrasound not only raised a lot of curiosity but also a little fear.

|

| Figure 10, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetus resting with its face against the placenta. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

Generally the women come to the clinic armed with a videocassette in order to record the pictures of the fetus: a film which they say they look at over and over again, showing it to their relatives until the next ultrasound examination. The reason, they say, is to become familiar with their baby and to be sure, in particular when the mother does not feel the baby moving, that the baby really does exist and moves.

Realistic images, such as those produced by three-dimensional ultrasound, succeed in involving the father-to-be in an event that might otherwise leave him feeling isolated and excluded.

|

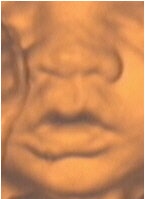

| Figure 11, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetal face at 27 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

The woman’s partner also suffers stress for the duration of the pregnancy. In a study by Villeneuve et al, the authors explain that the lack of direct experience of the pregnancy results in great interest and involvement in the ultrasound examination on the part of the partners. The authors quoted one father-to-be as saying, "The ultrasound exam is a very sentimental process, the exam is very important for me because it represents almost the only contact that I can have with the coming child. Having seen the image made me feel more attached to the baby because it has concretized the idea" (Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 1988, Vol. 33:6, pp. 530-536).

One husband who accompanied his wife for the first obstetrical ultrasound examination, on seeing the three-dimensional pictures, said "After having seen him like that, it would not be possible to have an abortion."

|

| Figure 12, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetal mouth and nose at 32 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

In general the women in our series readily collaborated at the interview. They were very willing to speak openly about themselves and their pregnancy, about their expectations and fears, and about their emotions after having had the 3-D obstetrical ultrasound examination. It was as if they felt compelled to clearly express their feelings after having been reassured by the pictures they had seen on the monitor, and by the reassuring words of the doctor.

The identification of the individuality and the separate existence of the baby generally provoked very strong positive emotions. The behavior of the baby and his posture were revealed and attributed to characteristics of one or the other parent:

- "He kept his hands between his legs; he’s reserved like his father!".

- "He was sucking the umbilical cord and slept all curled up: like his mother".

- "It’s incredible: he keeps his fists closed over his eyes: exactly like his mother when she sleeps!"

- "He has feet like mine and his face is like his father."

|

| Figure 13, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetus rubbing its eye with its hand and the umbilical cord in front of its mouth. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

Two women in particular demonstrated great satisfaction about their pregnancy. One of these two women, at the eighth month of pregnancy, told how she had previously undergone surgical intervention in order to become pregnant. When she finally had a positive pregnancy test she felt that this was an incredible occasion offered to her in life. Whatever the outcome of the pregnancy she felt that she had already received a great gift.

Interesting discussions of the conflicting emotions during pregnancy have been put forward by D. Fantoni and M.R. Rossi (Andreoli C et al. "Fattori Emozionali in Gravidanza: Loro influenza sul decorso e sull’esito" in "Fattori Emozionali in Gravidanxa, parto puerperio." Monduzzi Editore, Bologna, Italy, 1985).

|

| Figure 14, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetal hand at 34 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

Two women reacted negatively to the 3-D pictures commenting:

- "It’s a little monster: I’m very upset."

- "….right now it seems like E.T……: it’s very ugly."

During the interview one of these two women revealed the real motivation to her negative approach toward the examination. She explained that the same doctor, during a similar obstetrical examination of her aunt, had diagnosed the possibility that the aunt’s baby suffered from Down syndrome. These fears were later confirmed by amniocentesis.

Realistic pictures of the developing fetus do not correspond with the mother-to-be's imagined images of her future baby.

Only one woman when questioned about the transformation of her body stood up and showed her swollen abdomen, smiled, and turned to her husband questioning him "Am I no longer beautiful?"

|

| Figure 15, a 3-D ultrasound image of the male genitalia at 32 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

The majority of the women replied to this question saying "These are not important things" or "Even if I become fatter, afterward I will have time to diet…." The women were generally worried about the appearance of cellulite and stretch marks but above all there was fear about the actual delivery. "A pregnancy can be seen as one of the difficulties that psychologically unstable or disturbed women are not capable of facing" (Andreoli, C et al).

Birth, a separating event, defines a change and carries with it the fear of losing completeness, integrity, unity, and symbiosis. The child is no longer a part of the woman’s self, but becomes "another self."

|

| Figure 16, a 3-D ultrasound image of the female genitalia at 32 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

To have a child grow and develop inside the body does not guarantee that when he has his own separate existence from his mother, that he will overcome obstacles or difficulties and be capable of doing things with his own characteristics and traits.

Pregnancy and childbirth are composed of two essential aspects. The first is the concrete biological event. The second is the emotional or sensational experience caused by the physical event, which is never really recognized on a conscious level but felt and buried deep in the subconscious.

These sensations are reactivated throughout life in situations of separation or change. A conflict exists between the psychological need or desire for symbiosis and the biological necessity for separation. The psychological birth only becomes possible once the state of symbiosis with the mother comes to an end. Only in virtue of the emptiness that opens with the separation will one be able to experience the reality and accept the change that transforms (from De Benedetti and Gaddini-Novarino, Psychological Aspects of Birth; Stresa, Italy,1985).

|

| Figure 17, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetus at 13 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

To conclude, the pregnant women under examination showed a good level of maturity. This is evident by the fact that they actively and responsibly submitted themselves to preventative examinations. They chose to repeat the obstetrical ultrasound in a clinic with a good reputation in an attempt to obtain a satisfying explanation, to understand the meaning of the ultrasound pictures, and to clear up their doubts and their curiosities. In this way the 3-D ultrasound proposed immediately recognizable pictures that greatly aided the verbal feedback from the doctor. These 3-D images positively influenced the emotional state of nearly all of the women.

The impact of 3-D ultrasound: pictures making us conscious of the reality or pictures representing the reality of the subconscious?

Any pregnancy, no matter how welcomed, wanted, or planned, is a time of crisis for the woman and the couple due to the uncertainty of every change that accompanies it. A child, even in the best of circumstances, represents certain limitations for the life of any couple, and in particular the life of the mother. At every social level, in our western culture, this conflict is made apparent.

For example, the body, which becomes transformed during a pregnancy, must account for itself against our cultural models that determine the physical "must" that all women have to conform to. In some cases this can be very disturbing.

If we look at life as a procedure, a moment of crisis or change may be seen as an obstacle opposing this procedure, and not as an occasion of transformation. The human instinct is to remove the obstacle as quickly as possible in order to re-establish the equilibrium that existed previously and appears to be threatened.

Psychologically one knows this will not be possible, and that the crisis can be overcome only by facing the obstacle at hand. By avoiding the reality of the problem, Jung asserts that we are "remaining here on this side of the unpassable mountain that is blocking our life."

Almost always, in fact, the most significant moments in life require the separation of one’s self from someone or something. If one wants to use crisis as an opportunity to grow and evolve, one must give up that which previously gave life stability and equilibrium.

The human need to be the same in one’s self, to conserve one’s physical integrity and one’s psychological identity, contrasts directly with bodily developments necessary during pregnancy. Birreaux maintains that "the woman’s body is at the service of something that is not exactly her" and the baby may be thought of as a being that is "aggressively devouring."

Even when on a conscious level there is acceptance of the pregnancy, on the emotional level one may have hostile feelings, considered to be taboo and therefore not expressed but converted into symptoms of illness associated with the pregnancy (Fantoni and Rossi, 1985).

Pregnancy, with the involuntary feeling of transformation that accompanies it, evokes an uncertainty of mysterious changes. The disturbances of pregnancy are the direct result of the many biochemical changes the body must endure. They are also associated with the physical changes due to the presence of a kind of enemy. "The Unknown" is the name given to these disturbances expressed during pregnancy and represents the psycho-reality of the situation.

Therefore the pregnant woman submits herself to be investigated, controlled and monitored by medical specialists with all of their powerful equipment as required by the actual medical protocol. The healthcare service protocol controls the medical changes in the role of primary prevention for the mother-to-be; however, it does not fulfill her psychological needs.

This results in an ambiguous situation, in which the biological issues are addressed, but the fears and hesitations are ignored. The mother’s fears are not given an official space. Medical science establishes a preventive criteria excluding all that cannot be examined or controlled objectively. We must remember that in the attempt to provide satisfactory preventive medical care one creates expectations that extend beyond its limits.

Women want to be satisfied with the answers to all of their anxieties and fears. However, the medical protocol makes provision for investigations and provides reports limited to the programmed preventive level. All that is not concrete but belongs equally to the reality of the experience of pregnancy within the woman, contributing to her state of health, today still runs the risk of being excluded from the medical field.

|

| Figure 18, a 3-D ultrasound image of a fetus at 12 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Stefano Ciatti, M.D. |

The relationship between the doctor and patient was always a direct and privileged relationship based on a communicative exchange. Slowly but surely as medicine reached more sophisticated and organized levels, the doctor-patient relationship deteriorated. Little by little doctors have given up the use of talking or interviewing patients (delegating it to psychology?) giving more importance to clinical instrumentation which is continually more specialized (extension of the hand?) (Spinati, S., Etica Biomedica, Edizioni Paoline, Milan, 1987).

Thus humankind is divided, dissected and billed with the aim of being examined and cured more efficiently. This has undoubtedly had excellent effects on the health of the individual and on the health of entire so-called developed nations. However, it has also resulted in a paradoxical effect: modern medicine, so intent on curing humans of every illness, in the end, seems to have forgotten to actually "take care" of patients in their entirety. It is as though the vision of the whole being has been lost.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can confirm several interesting and important issues. Evolution of the role of women, both in society and in the family, has left them feeling more alone, especially when facing a pregnancy and all of the worries that accompany it. This has resulted in pregnancy, a natural physiological event, being transformed into an event of medical treatment and examinations. The technical application and impersonal preventive protocol through obstetrical ultrasound leaves women unhappy and dissatisfied, further adding to their state of anxiety related to the pregnancy.

Scientific development and technological evolution have placed great credibility in obstetrical diagnostic medicine. Further technological evolution brought about by 3-D ultrasound offers an occasion to regain some of the traditional rituals and customs, or in other words that human support, that once accompanied women during the nine months of a pregnancy which, we lament, has disappeared.

The pregnant woman attends an obstetrical ultrasound exam (almost) always accompanied by her husband/partner or else by a family member. The images recorded on the videocassette of the examination are later shown to relatives and friends even if they are little understood. When faced with 3-D ultrasound, the women find pictures that are immediately understandable, and therefore activate a state of reassurance resulting from the mere visible perception.

The direct understanding of 3-D pictures acts almost as an accomplice between the doctor and the expectant mother, accentuating a trusting relationship and a sense of reassurance. At the same time the doctor, assisted by clear and comprehensive 3-D pictures, is able to provide even more useful information, not only from a medical point of view, but also according to the woman's needs.

The immediate understanding of the pictures results in a certain sense of "possession" of the state of pregnancy to the mother-to-be, thereby contributing to her general well-being. The mother-to-be, along with the person who has accompanied her, can clearly see, without trying to decode, the pictures that the doctor is describing (and from which the report will be written).

The patient finds herself on a level of equality and parity with the doctor. This smoothes out the process of communication, particularly on the part of the woman who can more freely express questions relative to her doubts or fears in order to receive the necessary reassurance. The mother-to-be faces every 3-D sonographic examination with less anxiety, and leaves the doctor's office reassured.

Therefore, that which was initially introduced as a mere routine medical examination with the aim of prevention can in fact be associated with a new and modern type of ritual, replacing those traditions which used to accompany the mother-to-be in an affectionate way during her pregnancy.

Achieving such a benefit requires high-quality images, an attentive patient, and a doctor willing to make himself available to assist the patient in a suitable way. One must remember that showing an unclear picture (for example, the presence of shadowing or images obtained from poor scanning angles resulting in distorted and ambiguous images) can result in extremely negative consequences with very damaging and irreversible effects.

One can speak of 3-D ultrasound as a part of medicine that not only presents new possibilities to expectant mothers, but also for doctors and their assistants. The modality offers the challenge of promoting technical medicine by using this instrumentation in order to develop a new type of relationship that can heal the person and not only the disease.

By Stefano Ciatti, M.D., Lara Querci, and Dearbhla O’Dwyer

AuntMinnie.com contributing writers

December 30, 2003

Related Reading

Part I: The psychological impact of 3-D ultrasound on pregnant women, December 29, 2003

3-D ultrasound shows promise in neonatal, pediatric neurosonography, November 4, 2003

Turf Wars in Radiology IV: Radiologists, ob/gyns sound off on fetal imaging, September 26, 2002

Genetic ultrasound capable of preventing amniocentesis losses, July 8, 2002

Multinational study makes case for first-trimester sonography, June 12, 2001

Copyright © 2003 Stefano Ciatti, M.D., et.al.

Bibliography

- Andreoli C et al. "Fattori Emozionali in Gravidanza: Loro influenza sul decorso e sull’esito" in "Fattori Emozionali in Gravidanxa, parto puerperio." Monduzzi Editore, BO, 1985.

- Ayers S and Pickering AD. Opinion. Psychological factors and ultrasound: differences between routine and high-risk scans. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1997; Vol. 9, pp. 76-79.

- Belhassen W, Pons JC, Fournet P and Frydman R. Problèmes médicaux et éthiques posés par le diagnostic anténatal d’une amputation distale d’un membre. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Reprod. 1992, Vol. 21, pp. 475-478.

- Benacerraf BR. Editorial. Should sonographic screening for fetal Down syndrome be applied to low risk women? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, Vol. 15, pp. 451-455.

- Benvenuti P, Ciatti S, Whitney L et al. "The fantasized child and the fetus revealed by ultrasound scanning: reflections on the contrast between fantasy and reality in the ultrasound scanning experience in pregnancy". Med Psicosomat Vol. 33:215, 1988.

- Birreaux A. "L’adolescente e il suo corpo." Borla, Roma, 1993.

- Black RB. Seeing the baby. The impact of ultrasound technology. J. Genet Counsel 1:45, 1992.

- Blaicher W, Lee A, Deutinger J and Bernaschek G. Letters to the Editor. Sirenomelia: early prenatal diagnosis with combined two- and three-dimensional sonography. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, Vol. 17, pp. 542-545.

- Bronshtein M and Zimmer EZ. Editorial. Prenatal ultrasound examinations: for whom, by whom, what, when and how many? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, Vol. 10, pp. 1-4.

- Brown GF. Short-term impact of fetal imaging on parental stress and anxiety. Per and Peri-Natal Psychology Journal, 1988, Vol. 3, pp. 24-40.

- Budorick NE et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound examination of the fetal hands: normal and abnormal. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, Vol. 12, pp. 227-234.

- Colucciello ML. Pregnant Adolescents’ Perceptions of Their Babies Before and After Realtime Ultrasound. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 1998, Vol. 36:11, pp. 12-19.

- Cook PE and Howe B. Letters. Unusual use of ultrasound in a paranoid patient. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1984, Vol. 131, p. 539.

- Davalbhakta A and Hall PN. The impact of antenatal diagnosis on the effectiveness and timing of counseling for cleft lip and palate. Br J Plast Surg 2000, Vol. 53, pp. 298-301.

- Detraux JJ et al. Psychological Impact of the Announcement of a Fetal Abnormality on Pregnant Women and on Professionals. Annals New York Academy of Sciences, pp. 210-219.

- Don Francesco F. "Nello Specchio di Psiche", Moretti & Vitali, BG, 1996

- Dowswell T and Hewison J. Ultrasound examinations in pregnancy: some suggestions for debate. Midwifery 1994, Vol. 10, pp. 238-243.

- Du Bois P. "Il Corpo come Metafora", Laterza, Roma, 1990.

- Eurenius K, Axelsson O, Gallstedt-Fransson and Sjoden PO. Perceptions of information, expectations and experiences among women and their partners attending a second-trimester routine ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, Vol. 9, pp. 86-90.

- Eurenius K, Axelsson O and Sjoden PO. Pregnancy, Ultrasound Screening and Smoking Attitudes. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 1996, Vol. 42, pp. 73-76.

- Fantoni D e Rossi M.R. "Conflittualità in Gravidanza" in "Fattori Emozionali…." Cit.

- Fatemi M, Ogburn PL and Greenleaf JF. Fetal Stimulation by Pulsed Diagnostic Ultrasound. J. Ultrasound Med. 2001, Vol. 20, pp. 883-889.

- Filly RA. Guest Editorial. Obstetrical Sonography: The Best Way to Terrify a Pregnant Woman. J Ultrasound Med. 2000, Vol. 19, pp. 1-5.

- Gaddini Debenedetti R e Novarino D. "Aspetti psicologici del parto" in "Fattori Emozionali…." Cit.

- Harrington K. Opinion. The mid-pregnancy ultrasound assessment – quo vadis? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, Vol. 12, pp. 377-379.

- Hata T et al. Three-dimensional ultrasonographic assessment of fetal hands and feet. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol 1998, Vol. 12, pp. 235-239.

- Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Sabroe S and Secher NJ. The relationship between psychological distress during pregnancy and birth weight for gestational age. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1996;75:32-39.

- Heidrich SM and Cranley MS. Effect of Fetal Movement, Ultrasound Scans, and Amniocentesis On Maternal-Fetal Attachment. Nursing Research 1989, vol.38, no.2:81-84.

- Hosli I, Holzgreve W, Danzer E and Tercanli S. Two case reports of rare fetal tumors: an indication for surface rendering? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, Vol. 17, pp. 522-526.

- Julian-Reynier C et al. Diagnostic prénatal:connaissances des femmes à l’issue de leur grossesse. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 1994, Vol. 23. Pp. 691-695.

- Jurkovic D. Editorial. Modern management of miscarriage: is there a place for non-surgical treatment? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998. Vol. 11, pp. 161-163.

- Kovacevic M: The impact of fetus visualization on parents’ psychological reactions. Fifth Inter-national Congress of the Pre- and Perinatal Psychology Association of North America. Per- Perinat Psychol J. 1993, Vol. 8:83.---+

- Langer M, Ringler M & Reinold E. Psychological effects of ultrasound examinations: Changes on body perception and child image in pregnancy. J. Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol, 1988; 199-208.

- Larsen T et al. Ultrasound screening in the 2nd trimester. The pregnant woman’s background knowledge, expectations, experiences and acceptances. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, Vol. 15, pp. 383-386.

- Merz E. Opinion. Three-dimensional ultrasound – a requirement for prenatal diagnosis? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, Vol. 12, pp. 225-226.

- Michelacci L et al. Psychological Reactions to Ultrasound. Examination during Pregnancy. Psychother Psychosom 1998, Vol 50, pp. 1-4.

- Moeglin D and Benoit B. Letters to the Editor. Three-dimensional sonographic aspects in the antenatal diagnosis of achondroplasia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, Vol. 18, pp. 81-84.

- Neumann E. "Storia delle Origini della Coscienza", Astrolabio, Roma, 1978.

- Nikcevic AV, Tunkel SA and Nicolaides KH. Psychological outcomes following missed abortions and provision of follow-up care. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, Vol. 11, pp. 123-128.

- Persutte WH. Failure To Address The Psychosocial Benefit Of Prenatal Sonography: Another failing of the RADIUS Study. J Ultrasound Med. 1995, Vol. 14, pp. 795-796.

- Persutte WH. Editorial. "Complex problems have simple, easy-to-understand wrong answers."[Anon]…Effective communication in the practice of ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, Vol. 17, pp. 95-98.

- Pillai M and James D. Are the behavioural states of the newborn comparable to those of the fetus? Early Human Development 1990, Vol. 22, pp. 39-49.

- Raskin VD. Influence of Ultrasound on Parents’ Reaction to Perinatal Loss. Am. J Psychiatry 1989, Vol. 146:12, pp. 1646.

- Reading AE and Cox DN. The Effects of Ultrasound Examination on Maternal Anxiety Levels. J. Behav. Med. 1982, Vol. 5:2, pp. 237-247.

- Rice PL and Naksook C. Pregnancy and Technology: Thai Women’s Perceptions and Experience of Prenatal Testing. Health Care for Women International 1999, No. 20, pp. 259-278.

- Robinson J and Beech BAL. Risks of antenatal ultrasound. The Lancet 1990; Vol. 336:875.

- Salvesen KA et al. Comparison of long-term psychological responses of women after pregnancy termination due to fetal anomalies and after perinatal loss. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, No. 9, pp. 80-85.

- Sjostrom K, Valentin L, Thelin T and Marsal K. Maternal anxiety in late pregnancy and fetal hemodynamics. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1997; No. 74, pp. 149-155.

- Spinati S. "Etica Biomedica", Edizioni Paoline, MI, 1987.

- Stephens MB, Montefalcon R and Lane DA. The Maternal Perspective on Prenatal Ultrasound. J. Fam. Pract. 2000, Vol. 49:7, pp. 601-604.

- Strauss RP and Davis JU. Prenatal Detection and Fetal Surgery of Clefts and Craniofacial Abnormalities in Humans: Social and Ethical Issues. Cleft Palate J. 1990; vol. 27:2, pp. 176-183.

- Sweeney J & Bradbard MR. Mothers’ and fathers’ changing perceptions of their male and female infants over the course of pregnancy. J. Genet. Psychol. 1988, Vol. 149, pp. 393-404.

- Tautz S, Jahn A, Molokomme I and Gorgen R. Between fear and relief: how rural pregnant women experience foetal ultrasound in a Botswana district hospital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, Vol. 50, pp. 689-701.

- Thorpe K, Harker L, Pike A and Marlow N. Women’s Views of Ultrasonography: A Comparison of Women’s Experiences of Antenatal Ultrasound Screening with Cerebral Ultrasound of Their Newborn Infant. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, Vol. 36:3, pp. 311-315.

- Tsoi MM & Hunter MS. Ultrasound scanning in pregnancy: consumer reactions. J. Reprod. Inf. Psychol, 1988, Vol. 5:1, pp. 43-48.

- Villeneuve C, Laroche C, Lippman A and Marrache M. Psychological Aspects of Ultrasound Imaging During Pregnancy. Can. J. Psychiatry 1998, Vol.33:6, pp. 530-536.

- Zlotogorski Z et al. The Effect of the Amount of Feedback on Anxiety Levels During Ultrasound Scanning. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1996, Vol. 24:1, pp. 21-24.

- Zlotogorski Z et al. Anxiety levels of pregnant women during ultrasound examination: coping styles, amount of feedback and learned resourcefulness. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, Vol. 6, pp. 425-429.

- Zoja L. "Crescita e Colpa", Anabasi, MI, 1993.