Nonexperts can successfully use ultrasound to detect a full stomach in patients undergoing anesthesia, according to research published November 10 in the Journal of Clinical Anesthesia.

A team led by Sarah Baumann from the University of Basel in Switzerland found that examiners with limited experience in using ultrasound showed perfect sensitivity in detecting full stomachs. However, the examiners had limited success in determining whether patients had an empty stomach.

“Clinically, the high sensitivity is encouraging and suggests it is safe to detect a stomach at risk with limited experience,” the Baumann team wrote.

Patients are told to fast prior to undergoing anesthesia to avoid aspiration of gastric content, which is tied to high mortality and morbidity. Prior research suggests that ultrasound can accurately assess whether patients are fasting or not.

Baumann and colleagues noted the little evidence available that suggests inexperienced practitioners can use gastric ultrasound for this purpose. They put this idea to the test in a cohort of medical students performing gastric ultrasound. The students underwent blended online training, one plenary lecture, and two hours of hands-on training.

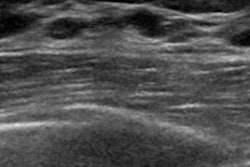

Representative images obtained during this study illustrating an empty (A) gastric antrum (outlined in red), one filled with liquid (B), and one filled with solid food components (C). Images available for republishing under Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).Journal of Clinical Anesthesia

Representative images obtained during this study illustrating an empty (A) gastric antrum (outlined in red), one filled with liquid (B), and one filled with solid food components (C). Images available for republishing under Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0).Journal of Clinical Anesthesia

The study included 80 volunteer patients. The research team randomized these patients in a 2:1:1 ratio to fasted, nonfasted fluid, and nonfasted solid categories. The medical students were blinded to the fasting status of the patients. An expert examiner also performed ultrasound exams on the patients for comparison.

The team reported the following findings from the medical students:

The students correctly identified all nonfasted volunteers (sensitivity = 1).

The students wrongly reported 18 out of 40 fasted volunteers as nonfasted (specificity = 0.55).

The students achieved a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.69 and a perfect negative predictive value of 1.

The students achieved an overall intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) value of 0.72.

Finally, the researchers found ICC values of 0.3 for fasted patients, 0.66 for nonfasted fluid patients, and 0.27 for nonfasted solid patients.

The study authors suggested that more focused training is needed to study the anatomy of an empty stomach on ultrasound. This will help reliably identify patients who are fasting prior to undergoing anesthesia, they wrote.

“This especially holds true for anatomically challenging patients, such as pregnancy or obesity,” the authors added.

The team also highlighted the importance of ultrasound’s use in this area as fasting is “not always guaranteed,” even in patients with a history of fasting and without comorbidities.

Read the full study here.