A pediatric radiologist at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) has developed an imaging augmented reality software application for use in planning liver transplants and surgery -- one that he hopes could not only reduce surgical times but also boost surgeons' confidence in their treatment plans.

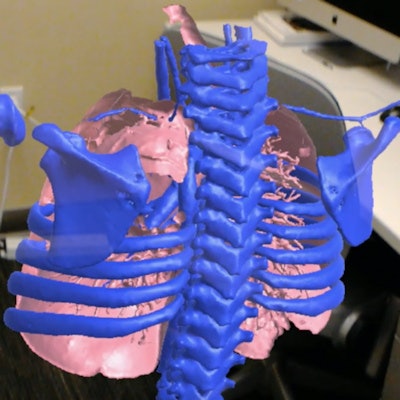

Dr. Jesse Courtier and virtual and augmented reality technology developer bencinStudios of Smyrna, TN, collaborated on the software, which is called Radiology with Holographic Augmentation (RadHA). It's used with Microsoft's HoloLens virtual reality computer to display 3D CT images of the liver, overlaid on a real-world background.

"We radiologists spend our day looking at 2D images and converting them to 3D in our mind," he said. "But that's tougher for surgeons, who are working with 3D organs. They come down to the reading room, look at the images, and take notes, but when they're in surgery they may encounter something they're not expecting. When I started to show them reformatted images in 3D, a light bulb went off."

Better surgical planning?

HoloLens is a self-contained holographic computer housed in a wireless headset that allows users to work with digital content in their real surroundings. The RadHA application lets radiologists visualize an organ from all angles, as well as in layers and particular colors, which gives physicians a better sense of a tumor's location, according to Courtier.

Courtier got the idea for RadHA while he was enrolled in UCSF's entrepreneurship program, Startup 101. He was looking for a way to offer surgeons images that could better help them plan procedures. Initially he considered 3D printing, but that technology can be expensive without reimbursement and also involve long turnaround times. That's when he began to consider hologram technology.

"I bought the HoloLens myself, and started playing around with it," he said. "Pretty quickly I realized I needed help from someone with gaming experience to take it to the next level, so I found Ben Howard at bencinStudios, and we worked together to develop the RadHA prototype."

Dr. Jesse Courtier from UCSF.

Dr. Jesse Courtier from UCSF.Currently, the application can use data from CT scans and some from MRI, such as MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI). Other potential clinical uses for the technology include tumor resections and oncology or brain surgery, Courtier said.

"We're hoping that the technology will help surgeons think through what type of surgical approach they'd like to take, even what type of incision, depending on where a tumor is located," he said. "That could save time in the operating room."

Going forward, Courtier and Howard plan to improve the application's interface with the help of input from surgeons. They've begun registration testing as well, evaluating how image measurements taken on PACS translate to the hologram.

"We're finding that we're within five-tenths of a millimeter in terms of accuracy," Courtier said.

Courtier also plans to continue evaluating the effects of the application on surgical performance measures such as whether using it reduces surgical time or boosts surgeons' confidence, he said. In addition, with support from UCSF's QB3 entrepreneurship program, he plans to continue improving the application so that image features can be processed automatically.

"To make the 3D models, a person has to process it," he said. "We're working on a way to upload CT data so that, for example, a user could pick out certain arteries or veins and they would be automatically rendered."

Radiology's purview

The technology could offer radiologists yet another way to demonstrate their importance to the healthcare enterprise, according to Courtier.

"This technology could be a way to keep ourselves in the mix, keep ourselves relevant," he said.

And who knows? Perhaps augmented reality could transform the practice of radiology in the future, Courtier said.

"What if this becomes the way we read images in 3D?" he said. "What if, in the future, we have holographic reading rooms?"