Radionuclide therapy for painful bone metastases:

Bone pain is a common complaint in patients with metastases - about three-quarters of patients with bone metastases have pain. Approximately 50% of bone metastases are due to breast, prostate or lung cancer. Approximately 80% of bone mets are found in the axial skeleton. The incidence of bone mets varies with the stage of disease:

Breast cancer: Stage I: 2%; Stage II: 6%; Stage III: 15%; and at time of first recurrence: 30%.

Prostate cancer: Stage A: 5-10%; Stage B: 10-15%; and Stage C: 20-30%.

The major clinical problem in these patients is pain relief. Analgesic and opiod agents are the first line of treatment for bone pain in cancer [2]. These agents may provide adequate relief of pain, but their utility is limited by a number of adverse side effects such as constipation and limitations on physical and mental status [2]. For prostate cancer the response rate to hormone therapy is 70% to 85% with response lasting on average up to 12 months. Once patients with advanced prostate cancer fail hormonal therapy, the outlook is poor with a median survival of about 9 months. Radiation therapy can also provide partial or complete pain relief in 80-95% of cases. It is particularly useful for local treatment of a solitary metastatic site or a small number of sites. When wide field therapy is required (i.e.: multiple bone lesions), pain relief is less effective and complications such as thrombocytopenia, GI symptoms, and pneumonitis become more frequent [1,2]. Recurrent pain within a previously treated field of radiation is also difficult as the tolerance of normal tissues may limit the use of additional radiation [2]. Finally, chemotherapy can also reduce bone pain- however, toxic side effects- especially myelosuppression- are very common [2].

Radionuclide therapy is an alternative to other means of pain control from bone metastases. The goals of radionuclide treatment are to alleviate pain, improve quality of life, improve mobility, reduce dependence on narcotic and non-narcotic analgesics, improve performance status, and possibly survival. By alleviating pain, these agents can also reduce treatment costs by eliminating the need for external beam radiation and analgesic medication [2].

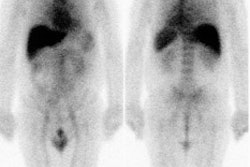

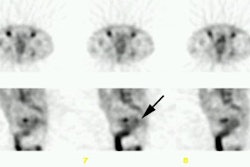

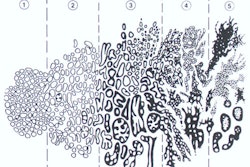

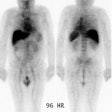

The best candidates for radionuclide therapy are patients with advanced cancer who have more than one metastatic lesion and are not candidates for, or are refractory to, conventional analgesic medical treatments. Patients should have an estimated life expectancy of at least 3 months [4]. It is important to distinguish bone pain from pain due to neuropathic syndromes or visceral pain as the agents are not effective in palliating non-bone pain. The bone scan is a useful tool to confirm that the patient has multiple sites of bone metastases. The patient's pain should emanate from the areas shown to be abnormal on the bone scan. The abnormal bone scan indicates increased osteoblastic activity and the deposition of the therapeutic agents should correspond to this distribution [3]. The agents therefore have a high target-to-non-target ratio and they are also preferentially retained for a longer period of time in areas of osteoblastic metastatses compared to normal bone [3]. Optimal results of therapy are seen when sites of pain match areas of increased uptake on the bone scan [5]. Pain not arising from sites shown to be abnormal on the bone scan should not be considered for this treatment. Response is less predictable in patients with predominantly lytic skeletal mets (likely due to poor uptake and retention with a lower absorbed radiation dose) [5].

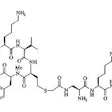

The radionuclide agents used for palliation of metastatic bone pain are easily administered on an outpatient basis. The agents include Phosphate-32, Strontium-89, and Samairum-153 (Rhenium-186 is not yet approved for use in the United States). These radiopharmaceuticals act systemically to reach all sites of metastatic disease. Pain relief is not immediate, but generally occurs within 5 days to a couple of weeks (agent dependent) and can last several months. One must be careful not to infiltrate the tissue at the injection site as this can result in tissue necrosis. Treatment should be tailored to the individual patient. Patients with relatively early metastases, a favorable life expectancy (over 6 months), reasonable pain control with analgesics, and normal marrow function are likely to obtained a sustained benefit from Sr-89 therapy [5]. By comparison, patients with advanced metastases, severe pain, and limited marrow reserve would be more appropriately treated with Sm-153 or Re-186 [5].

The primary adverse effect of all of the agents used for palliation of painful bone metastases is transient mild-to-moderate myelotoxicity developing between 4-8 weeks after therapy [5]. This is uncommonly of any clinical significance [3]. However, blood counts should be obtained at least weekly for the first 6 weeks following treatment [4].

Patients that may be excluded from radionuclide therapy include:

1- Patients with pain from other causes which is mimicking bone pain

2- Patients with low white blood cell count (ANC less than 1500), low platelet count (less than 60,000), or low hemoglobin (less than 90 g /L) [4]. Also, radioisotope therapy should not be given 6 weeks before or following myelosuppressive chemotherapy.

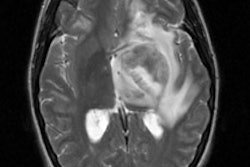

3- Patients with impending spinal cord compression or impending long bone fractures as evidenced by greater than 50% cortical erosion. These conditions should be considered surgical or radiotherapeutic emergencies [5]. Fracture stabilization should be performed prior to or concurrently with radioisotope treatment.

4- Patients with compromised renal function- Poor renal function will delay clearance of most bone seeking radiopharmaceuticals leading to a higher whole body dose and increased toxicity [5]. These patients can receive treatment, but certain cautions must be exercised such as reducing or splitting the dose to be used. Patients with severe renal failure (GFR less than 30 mL/min) are not candidates for therapy [5].

5- Patients receiving other phosphonate-based therapies (such as pamidronate) within 2 to 3 days of treatment- These agents can compete for the same binding sites on bone as do the radioisotopes, possibly reducing the efficacy of both agents.

6- Pregnant patients are not candidates for therapy

REFERENCES:

(1) J Nucl Med 2000; Kolesnikov-Gauthier H, et al. Evaluation of toxicity and efficacy of 186Re-Hydroxyethylidene diphosphonate in patients with painful metastases of prostate and breast cancer. 41: 1689-1694

(2) J Nucl Med 2001; Serafini AN. Therapy of metastatic bone pain. 42: 895-906

(3) Semin Radiat Oncol 2000; Silberstein EB. Systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy of painful osteoblastic metastases. 10: 240-249

(4) J Nucl Med 2004; Pandit-Taskar N, et al. Radiopharmaceutical therapy for palliation of bone pain from osseous metastases. 45: 1358-1365

(5) J Nucl Med 2005; Lewington VJ. Bone-seeking radionuclides for therapy. 184: 38S-47S