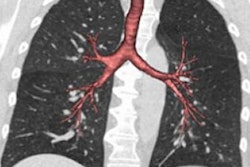

CT shows that cardiopulmonary fitness reduces the long-term risk of bronchiectasis, a serious airway disease that can lead to the buildup of bacteria and mucus in the lungs and impair breathing, according to a study published April 27 in Radiology.

The study findings are good news for everyone, since fitness is an intervention that can be implemented with relative ease, according to a team led by Dr. Alejandro Diaz of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

"Our results suggest fitness might be a modifiable factor that can contribute positively to the preservation of airway health," the group wrote.

Bronchiectasis manifests as cycles of inflammation that damage a person's airways -- leaving them enlarged, scarred, and less able to clear mucus and thus more vulnerable to infection, the team noted. There's no cure for the condition, and the factors that might reduce a person's risk of developing the disease are unclear, although some researchers have hypothesized that exercise may help.

"High levels of fitness are associated with reduced systemic inflammation, and chronic inflammation leads to recurrent infections resulting in structural damage of proximal airways, a central feature of bronchiectasis," the authors wrote.

Clinicians already use CT to evaluate patients presenting with shortness of breath or coughing up mucus for bronchiectasis; Diaz and colleagues sought to investigate any connections between heart and respiratory health due to exercise and reduced risk of bronchiectasis. To do so, they conducted a study that included data from 2,177 healthy people between 18 and 30 who participated in the Coronary Artery Disease in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, which began in 1984.

The study participants were tracked over 30 years and underwent periodic fitness tests and CT exams. Diaz's group particularly focused on data from baseline and year 20 cardiorespiratory fitness evaluations (treadmill tests) and CT data from year 25 to determine changes in fitness measured by treadmill test duration were associated with the development of bronchiectasis.

The group found that of the total number of participants, 9.6% (209) had bronchiectasis at year 25 of the study, and that cardiorespiratory fitness reduced the odds of having the disease at this juncture by 12%.

"In an adjusted model, one-minute longer treadmill duration between year 0 and year 20 was associated with 12% lower odds of bronchiectasis on CT at year 25," Diaz said in a statement released by the RSNA.

This positive effect could be due to the fact that cardiorespiratory fitness lowers levels of systemic inflammation, which could protect airway health, and that it also reduces risk of diseases such as asthma and pneumonia and improves the body's ability to clear mucus from airways.

"These results amplify the benefits of fitness to human health when a sedentary lifestyle is a concerning world epidemic," Diaz said. "It also highlights that fitness might be a tool to preserve lung health."